Posted by Marc Hodak on October 30, 2013 under Executive compensation, Governance, History, Unintended consequences |

The last time that CEOs were routinely kept awake at night was during the merger wave of the mid-1960s.

The frothy ’50s turned out to be high tide for American industrial dominance, a time when we were rebuilding the world after a devastating war. CEOs had it pretty cozy then. As the tide began to recede, investors began to notice the accumulated waste made possible by a decade of easy growth. A few of them saw advantage in taking over the worst governed companies in order to restructure them. At that time, they could do so without warning, which is what made this environment so frightening to CEOs. Imagine never knowing when you might get a phone call telling you that you are out. This is like going trick-or-treating and fearing the “tricks” all year long.

Corporate executives of that period had grown up in a world where being a leader meant getting along with everybody, and knowing how to use the corporate treasury to buy allegiances, including labor, business partners, and politicians. These new people on the scene—called “raiders”—were after the whole treasury, in part to prevent it from being used as the CEO’s relationship kitty. The governance mechanisms of the day gave them access to it by simply taking advantage of the stock being cheap after years of neglect.

Worried incumbent CEOs reacted by contacting their congressmen, who also knew a thing or two about incumbency. This unholy partnership took control of the narrative. Instead of investors identifying bloated companies in order to restructure them and return excess funds to remaining shareholders, the incumbents claimed that:

“In recent years we have seen proud old companies reduced to corporate shells after white-collar pirates have seized control with funds from sources which are unknown in many cases, then sold or traded away the best assets, later to split up most of the loot among themselves.” (Sen. Harrison Williams, 1965)

The media bought it. The legend of the “corporate raider” was born. The off-hand mention of “unknown” funding sources added a hint of nefariousness. (Who did they think provided the funds? Why did it matter?) The media didn’t consider that any mechanism that made the sum of the parts worth so much more than the whole might actually be socially useful. Instead, they played on the conservative discomfort of seeing old line, industrial firms disappearing at the hands of destabilizing (and generally non-WASP) upstarts, and the liberal discomfort of “money men” involved in unregulated financial activities.

Thus, in the fall of 1968, Congress passed the Williams Act. This law prevented investors from making a tender offer for shares without giving incumbent boards and management a chance to “present their case” for continued control of the company—as if they hadn’t already had years to make their case.

Now comes the weird part. Read more of this article »

Posted by Marc Hodak on October 14, 2013 under Governance, History |

"More lucky than good"

Consider that you are on the board of a company of adventurers, and one of your captains, Chris Columbus, comes to you with a project.

“The learned people all think that the world is flat. Our R&D indicates that the world is round. If you fund our voyage, we will be able to obtain the wealth of the Indies spice trade via a shorter route from the west instead of from the east.”

One director chimes in, “But Chris, all the experts say that the world is flat, and that the western route is terra incognito. Why don’t you think you won’t simply fall off the edge of the world?”

Chris replies: “The experts are wrong. Here is my data. Fund me, and glory will be ours.”

According to the story we were taught in school, Columbus was not able to get money from the usual channels that might fund a sea voyage, and it was the bold bet by Queen Isabella that launched him toward America and legend. In this story, Isabella was the perspicacious investor behind a brilliant, if misunderstood, CEO. Her good bet paid off in the bounty of a New World, and all those investors who wouldn’t back Columbus were fools who lost out.

What really happened looked like this.

Chris Columbus tells the board: “The learned people say that the world is a very large sphere, about 20,000 to 30,000 miles around. Our R&D indicates that the world is only about a third of that size around, meaning we can more easily obtain the wealth of the Indies spice trade via a shorter route from the west instead of from the east.”

One director chimes in, “But Chris, if the experts are just a little more correct than you are, you will simply run out of supplies on your voyage, and die.”

Chris replies: “The experts are wrong. Here is my data. Fund me, and glory will be ours.”

The real Columbus was not able to convince anyone with any learning that a western route to the Indies was shorter than the eastern route that was already established. He was able to convince a Queen with more wealth than knowledge. She enabled him to set out on what, by all rights, would have been a voyage to oblivion. Just as his supplies were running out, he stumbled upon the New World.

Boards of directors have basically one job—to make good bets and avoid bad ones with their shareholders’ funds. This is a difficult job under the best of circumstances, which necessarily includes incomplete information and a limited range of capabilities, including the normal biases and dynamics of even well functioning groups. On top of that, they must deal with the bane of businessmen everywhere—luck.

In the mythical Columbus story, the adventurer and the Queen made a good bet, and won. In the real story, they made a bad bet and won. The problem for directors is that the world only sees results; it cannot see the quality of the bets that led to them. Columbus’s bad bet was redeemed by an accident of incredible fortune. The Queen appeared to disprove the adage about a fool and her money, and the investors that wisely turned down Columbus’s bet were ridiculed for a missed opportunity.

Obviously, each of us would prefer a board that makes winning bets rather than losing ones on our behalf. But no one can dictate the outcomes of our bets. The only thing we control is the quality of our bets. By definition, good bets are more likely to pay out than bad ones. A board that effectively distinguishes these things should be more effective. But they can still lose. The world isn’t fair.

I have seen well-meaning boards make reasonable bets and end up lambasted on the front page of the Wall Street Journal for looking foolish. I have seen boards that were in over their heads nonetheless feted when the wind found their backs. The business world looks very different to those of us who are on the inside versus those reading the stories. We know that the world is not fair, and deal accordingly.

My Columbus Day message is this: We should always strive to be good, and hope we are also lucky. In life, if not always in business, we are generally blessed with many chances to succeed or fail. Over time, good luck and bad will tend to even out, and the quality of our decisions should show through. Even then, though, luck has a say.

Posted by Marc Hodak on October 6, 2013 under Governance, Patterns without intention |

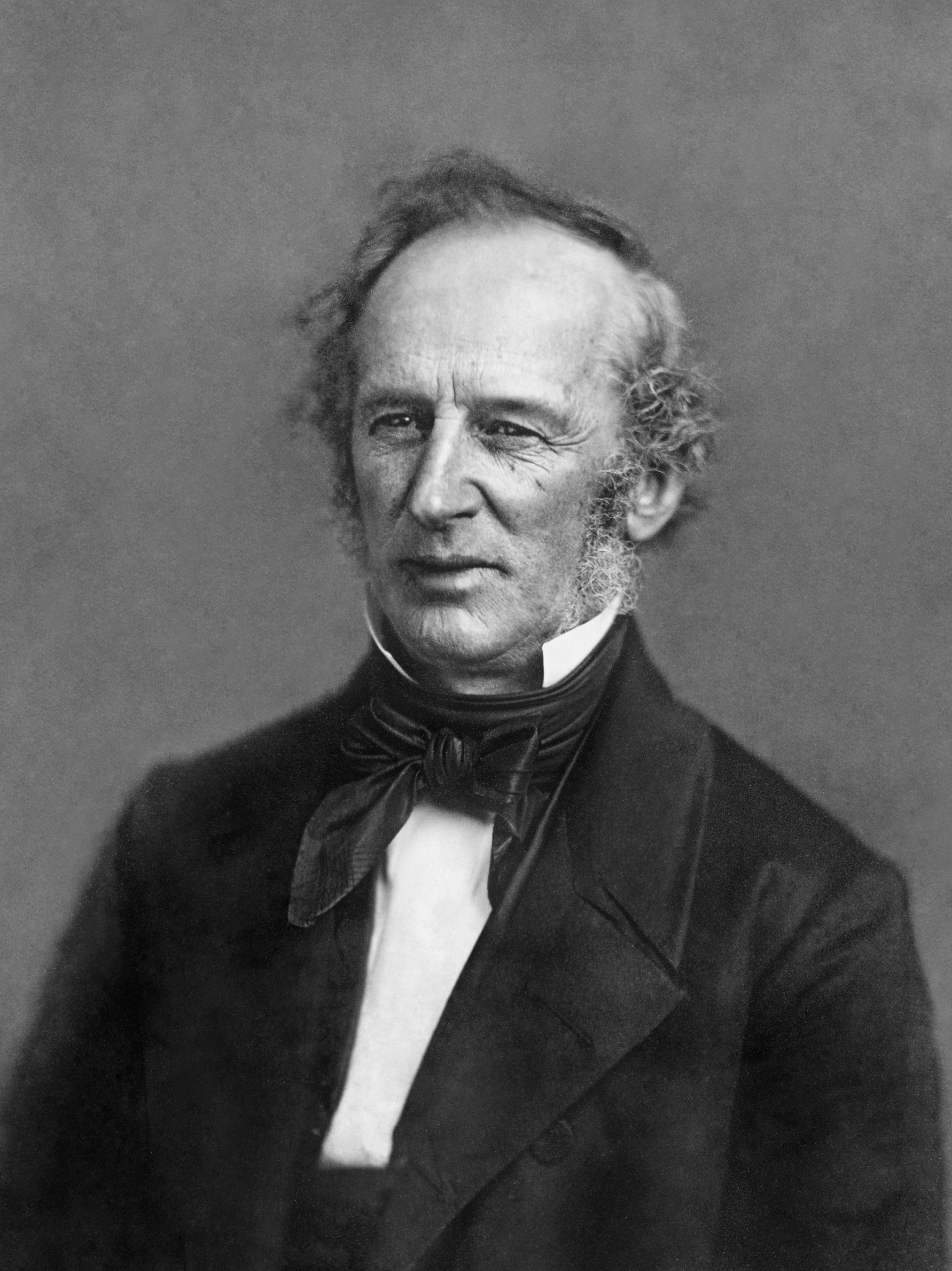

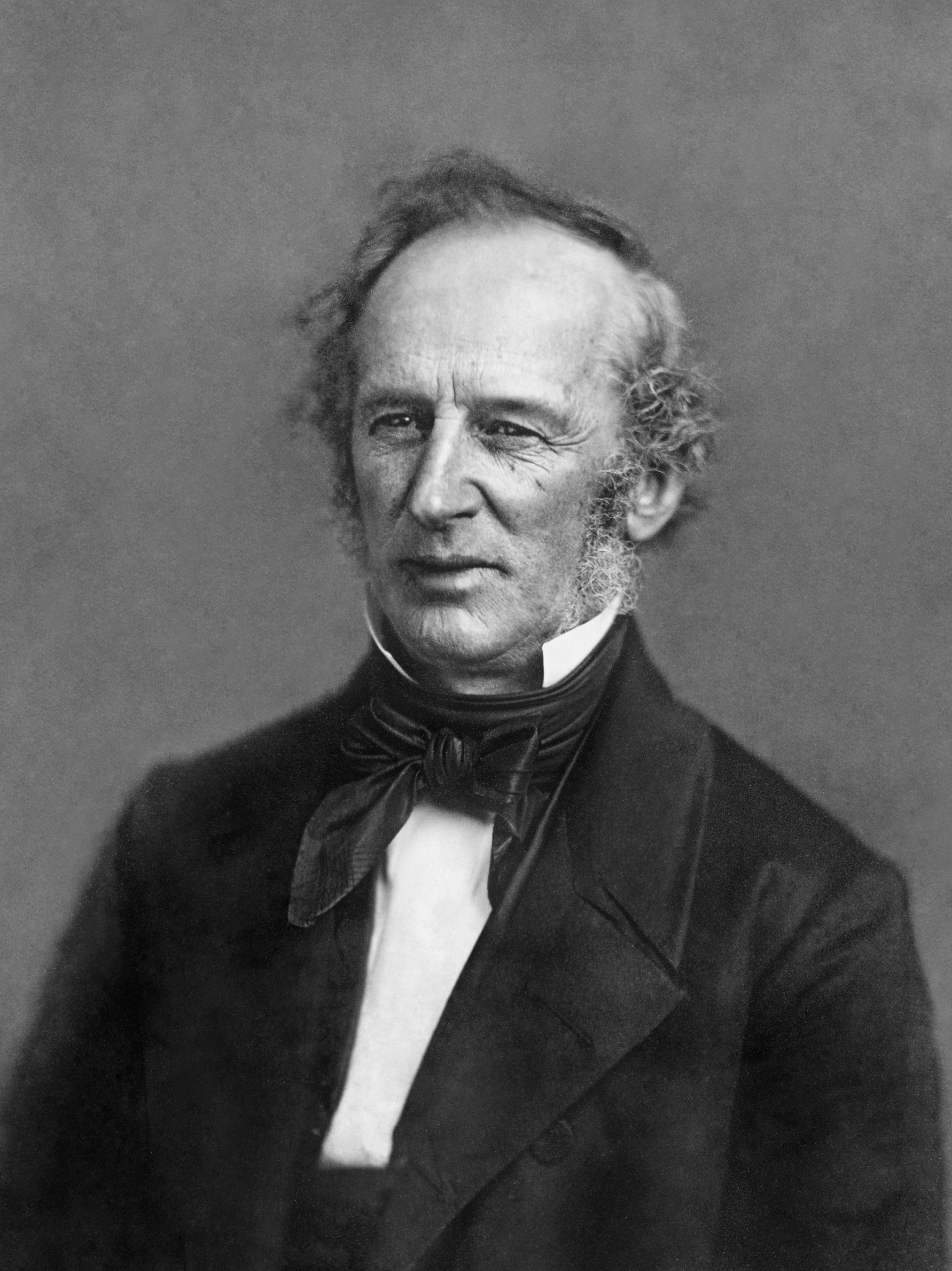

"The public be dammed" (sic)

Churchill famously remarked that “democracy is the worst form of government, except for all the others.” This is a great lead-in to distinguishing democracy as a collective decision making process that is useful for some purposes, but not for others. For instance, democracy is not well suited as a decision mechanism for running a company. You haven’t heard of a company run as a democracy? There’s a reason for that.

In fact, when we look at the governance spectrum for companies as ranging from democracy (e.g., shareholder-run firms) to oligarchies (e.g., board-run firms) to dictatorships (e.g., “imperial CEOs”), it is worth noting that the overwhelming percentage of wealth created in this country was by imperial CEOs, folks like Ford, Disney, and Jobs. Imperial CEOs also fail, of course, sometimes spectacularly. When they do, corporate critics pounce and say, “See? An imperial CEO runs the company into the ground! If there had been more checks and balances, more shareholder involvement or awareness, this would never have happened.” It is very hard to argue against that. Except that no company run as a shareholder democracy has ever generated enough wealth to even be worthy of a scandal.

Today, we are hearing the drumbeat about the evils of “shareholder value.” Here is one drummer, Lynn Stout, beating on shareholder value:

The idea that corporations should be managed to maximize shareholder value has led over the past two decades to dramatic shifts in U.S. corporate law and practice. Executive compensation rules, governance practices, and federal securities laws, have all been “reformed” to give shareholders more influence over boards and to make managers more attentive to share price. The results are disappointing at best. Shareholders are suffering their worst investment returns since the Great Depression; the population of publicly-listed companies has declined by 40%; and the life expectancy of Fortune 500 firms has plunged from 75 years in the early 20th century to only 15 years today.

Stout, like many other corporate critics, is conflating the movement for shareholder value that gathered steam in the early 1980s with the movement toward shareholder democracy that gathered steam in the early 1990s.

These are different things.

Read more of this article »

Posted by Marc Hodak on September 22, 2013 under Executive compensation, Politics, Stupid laws, Unintended consequences |

The SEC has finally proposed a rule on the infamous “CEO Pay ratio,” i.e., the ratio of CEO pay to that of the median worker. There has been plenty of debate about the pros and cons of this requirement. The primary criticism is that this ratio will not pass any cost/benefit analysis. Every company knows this is true. Most institutional investors know it, too, and don’t really care for this rule. In fact, the only people likely to benefit from this rule are the unions that pushed for it. Even their benefit is speculative since the unintended consequences of this rule are difficult to fully predict. For instance, it might encourage further outsourcing of relatively low-wage work to foreign companies, depressing employment. In other words, we could very well see the average pay of the median worker go up, but only if you don’t count the zero wages being earned by those who are laid off as a result of this law.

Given how dubious are the benefits of this rule, let’s turn to the costs. I have seen estimates of calculating this ratio for a large, multinational firm as high as $7.6 million. Being in the advisory business, that seems pretty excessive to me. By comparison, the average cost of complying with the dreaded SOX Section 404 was about $2 to $3 million for the typical company (which was about 10 times higher than the SEC estimated it would cost when they published its rules).

So, let’s say it costs about $2 to $3 million for a large company, which is a reasonable estimate for a multinational given the way the rules look right now. Well, about 10 percent of Fortune 500 CEOs made less than that in 2012. That’s right, we are almost certain to see quite a few companies paying more than they actually pay their CEO to figure out how much more their CEO makes than their median worker.

If this rule was really being implemented for the benefit of the shareholders, then Congress could have let each company’s shareholders opt in or opt out of this disclosure regime. Clearly, the people pushing this ratio had no interest in giving actual shareholders a veto over this racket.

Posted by Marc Hodak on September 15, 2013 under Executive compensation, Irrationality |

A pair of recent studies show that about a quarter of the compensation earned by CEOs is now paid as restricted stock. Furthermore, one of the studies notes that an increasing portion of that stock is being granted based on performance rather than automatically vested over time, and that stock price is one of the most common performance measures used to determine the number of shares granted. In other words, if the stock price goes up (or goes higher than some benchmark), then the executive would benefit from both the larger number of shares granted and the higher price per share. If the stock price goes down, the executive will get fewer shares at a lower price, or maybe no shares at all. The governance mavens are praising this trend.

There is a lot to like about ‘performance share’ plans, and stock-based stock grants provide an exceptional level of motivation and accountability for total shareholder returns over a wide spectrum of performance over time. So, I’m wondering: Why is this kind of plan legal?

Read more of this article »

Posted by Marc Hodak on August 23, 2013 under Executive compensation |

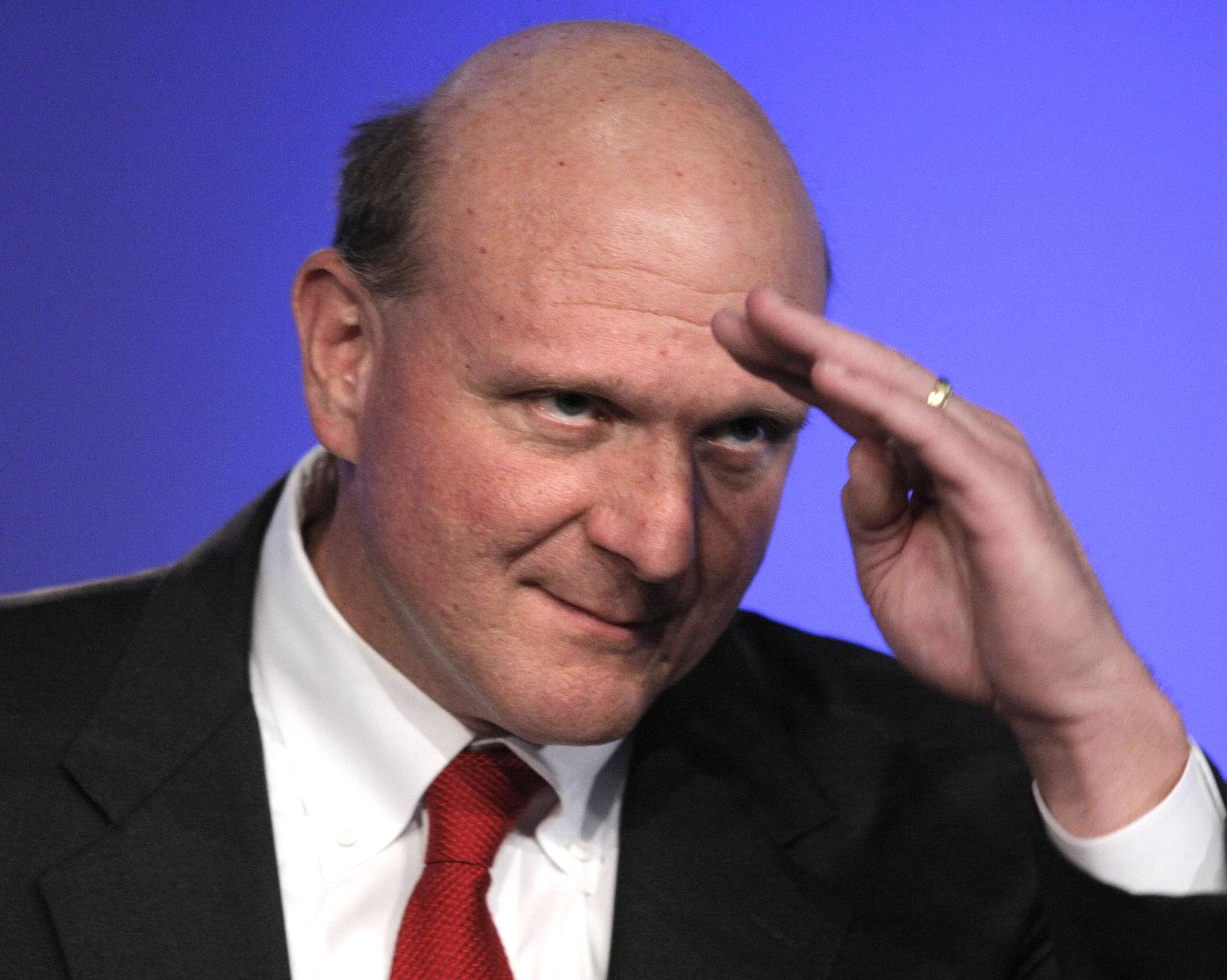

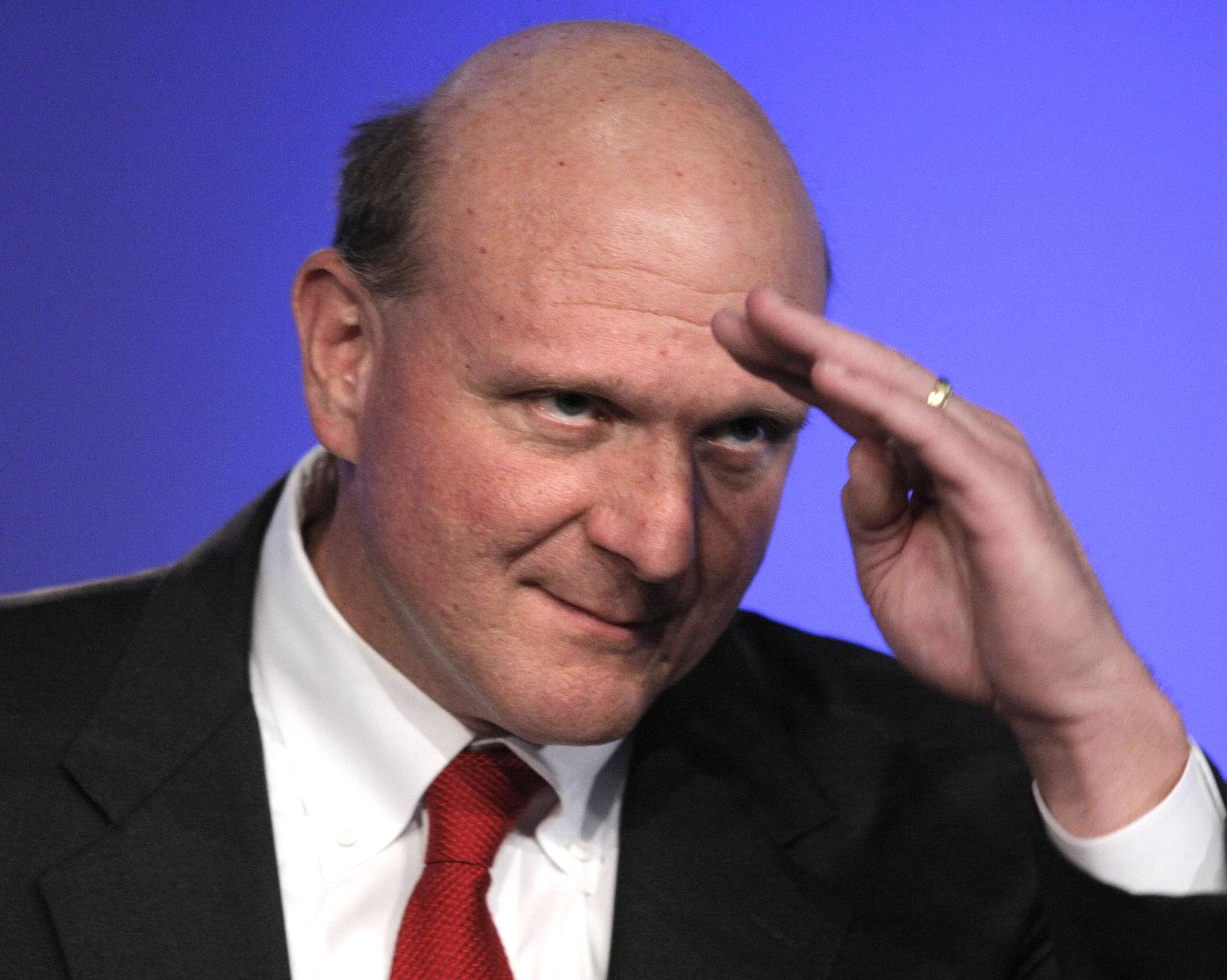

The other Steve

Steve Ballmer announced his resignation, and Microsoft’s stock price shot up seven percent. Ouch.

That investor verdict is far more damning than anything shareholders could have conveyed through a proxy vote. It tell us pretty directly what the market thinks about Ballmer or, more specifically Ballmer’s leadership relative to anyone that Microsoft is likely to hire as his replacement.

One way to read this reaction is that Ballmer has been a roughly $19 billion drag on his company. This deficiency might have been inferred by the fact that Microsoft’s stock has gone exactly nowhere* in the decade that Ballmer has been CEO, significantly underperforming the Nasdaq, not to mention its closest competitors Oracle, Google, and especially Apple. I’m sure Steve Ballmer is in for many unflattering comparisons to Steve Jobs in the upcoming weeks.

I’m not here to bury Ballmer, or to praise him, but to highlight how this coda of his tenure reflects on the value of a “typical” CEO. I often hear how a CEO doesn’t do it alone–he or she is part of a team. I often hear people questioning whether the average CEO is worth the $15M to $20M per year that they get paid, or whether any CEO “needs” the $100 million they may have gotten paid in a year of outstanding performance. I have answered these questions in prior blog posts, so I will encapsulate them here.

1) Sure, a CEO is just one person on a team, but the CEO ultimately selects and manages that team, amplifying or cancelling their talents. His or her marginal contribution is still very large.

2) Ballmer illustrates that a CEO may be worth much less than $20 million per year. Other CEOs, like Jobs (OK, I’m starting the comparisons), are worth much more than $20 million per year. The stock reaction when Jobs announced his resignation was a drop of about $10 billion, although his announcement was not entirely unexpected. So, how plausible is it that the average CEO is worth about $20 million per year? More plausible than $2 million or $200,000 per year, although the value variance around that average is obviously very high.

3) No person “needs” $20 million or $100 million or any such astronomical sum. But nobody this side of the Soviet Union gets paid according to their need. If things are working right, they get paid what they’re worth. This correspondence is never perfect, but we haven’t yet found a better way.

By the way, Ballmer earned about $1.3 million per year in salary and bonus as CEO of Microsoft, much less than a typical Fortune 500 CEO, but not out of line for someone whose personal net worth likely went up and down about $100 million a day due to his MSFT stock holdings which, as mentioned earlier, didn’t net him anything more than he started with over his tenure. In other words, alignment wasn’t an issue for Ballmer. Maybe he just decided he didn’t need any more? Maybe he wasn’t greedy enough?

* I’m being generous here by tagging the stock’s fall in his first year as an artifact of the dot-com bust.

Posted by Marc Hodak on July 28, 2013 under Executive compensation, Governance, Invisible trade-offs |

I am often dismayed by the popular response to “dollar-a-year CEOs.” These bosses give the media a feel-good story: You don’t have to be greedy. You can be a not-so-fat-cat!

Apparently it’s not just John Q. Public–several times removed from the real world of compensation governance–that buys this stuff. Just last week, a tech company CEO in a WSJ “expert” panel praised the dollar-a-year standard, and the swell guys and gals who adopt it, saying that all CEOs should be so virtuous.

These are people that are out to change the world. They are owners. They are builders. They bleed for their company and what they are creating. It’s not about the money.

His examples were Steve Jobs, Larry Ellison, Mark Zuckerburg, Meg Whitman, Larry Page. Do you see a pattern (besides all the money)?

Read more of this article »

Posted by Marc Hodak on July 23, 2013 under Governance, History, Invisible trade-offs |

The birth of a new British heir once again causes us governance geeks to scratch our heads at the succession mechanism formally known as primogeniture, the winner-take-all system whereby the first-born (generally male, but not always) becomes heir to substantially all of the parents’ titles and property. In the context of a monarchy, has anyone ever believed that such a mechanism would consistently yield good leaders?

The answer, of course, is “No,” but the question assumes the wrong purpose. In fact, primogeniture did not evolve as a way to select a certain quality of leader; it evolved as a way to enable society to accumulate capital.

For most of history, it was extremely difficult to preserve and grow capital from one generation to the next. Before the 19th Century, the lives of ordinary people–how they labored and what they had in their homes–were virtually indistinguishable from that of their grandparents. Things were hardly better among the aristocracy. For them, accumulated property was basically an invitation to plunder. Consequently, from the Fall of Rome to the Industrial Revolution, the vast majority of capital created by the upper classes was in the form of weaponry, and most of that was consumed in battle. It was in this neo-Hobbesian war of all against all that primogeniture evolved as a way to select kings.

The customary transfer of allegiance of powerful nobles from their king to a royal heir greatly reduced the odds of a civil war. Societies that tended to avoid civil war tended to accumulate far more capital. More capital made them more powerful, economically and militarily, creating a dynamic that eventually led to the institution of monarchical succession via primogeniture spreading throughout most of the world.

Read more of this article »

Posted by Marc Hodak on July 10, 2013 under Governance |

This week we celebrate the 65th anniversary of the Roswell crash landing, a watershed event for conspiracy theorists everywhere. I sympathize with the hapless Air Force officers looking at the wreckage of their high-altitude weather balloon, the glass, rubber, and metal strewn around, probably including a reflective saucer-shaped instrument shell, and having to explain within the bounds of military secrecy what happened that night, only to be met with the suspicion of people wearing tin-foil hats. The chagrin of those officers must have turned to alarm as the fallen balloon was figuratively resurrected, and the flying saucer took off as one of the enduring stories of our time: A crash landing by stray aliens being covered up by the U.S. government for its own nefarious, if unspecified, purposes.

The reason I can easily sympathize with the government on this is because I have seen an even bigger conspiracy theory that I personally know to be equally ludicrous—the conspiracy of corporate leaders to control the U.S. political and economic machinery to their personal benefit. A whole phalanx of academics, journalists, and elected officials has benefited from the public’s credulous acceptance of this theory, especially with regards to executive pay.

Lest I be accused of creating my own anti-“corporate conspiracy” conspiracy theory, let me quickly add that each of these parties has participated in their part of the anti-corporate crusade according to their own particular incentives, i.e., to publish in select journals, sell newspapers or airtime, or win higher elected office. No coordination was necessary to blow this balloon beyond what reality could contain.

Read more of this article »

Posted by Marc Hodak on July 1, 2013 under Governance, History |

As we celebrate the birth of our country this week, I think it’s worth reflecting on the United States as history’s most daring experiment in governance.

Most of us were taught the Constitution in middle or high school as a series of clauses defining the various workings of our federal government. Some concepts such as “checks and balances” managed to penetrate our pubescent fog because the idea of constraints on authority is innately appealing to young people. But few of us were left with a sense of how bold an innovation our Constitution was at the time of its adoption, or how fragile was the republic that it created. Understanding those things greatly enhances one’s appreciation of the American civilization that would emerge from that experiment.

Read more of this article »