Posted by Marc Hodak on July 28, 2015 under Governance |

Mylan’s anaphylactic reaction to a generous offer

The headline quote comes from Mylan’s Executive Chairman Robert Coury, in response to why his firm was rejecting a rather generous buyout offer from Teva.

I get it. Coury believes in the long term. He believes that “shareholders benefit from a well-run business, and to run a business well, you need to focus on all of the stakeholders we touch on a daily basis, including customers, patients, employees, suppliers, creditors and communities.” Mylan used that to defend a decision that would cause its stock to drop over 30 percent below the value of Teva’s offer, yielding a collective value deficit of $10 billion.

As a shareholder, I would love to know how Mr. Coury’s expansive focus on his stakeholders will make up for that $10 billion opportunity cost. That’s a lot of EpiPens.

Alas, Mr. Coury doesn’t have to give a [vloek] about what shareholders want to know. Even if they voted off all of the board members, he retains the sole right to appoint new ones. That’s the kind of power that would get good governance folks in America to freak out.

Or be perfectly OK with it, depending upon one’s perspective.

Read more of this article »

Posted by Marc Hodak on July 13, 2015 under Economics, History, Politics |

“We can make them sign it. What can go wrong?”

The Germans, who are normally quite astute about the lessons of history, are now acting against Greece with what looks like a vindictive intransigence that would have made Allied negotiators at Versailles nod approvingly. The Greek’s choice now appears to be between another bailout and continued harsh austerity, or default and financial collapse. Who in Europe believes that pushing Greece into desperate economic straits is good for their stability? Will it take the rise of someone much more extreme than Tsipras to make the Germans, French, and others understand what they are really getting in exchange for avoiding another haircut on the loans, and accepting any responsibility for the bad judgments of the lenders as well as the borrowers?

Greece may have another choice. Two choices, actually: an economic choice and a political choice.

The economic choice, under a rational leadership, may enable Greece to default on their outstanding debt and quickly resurrect their access to global capital markets at reasonable rates. This choice would merely require a couple of changes in their constitution. It has been done before. To see how, we need to step further into history.

Read more of this article »

Posted by Marc Hodak on July 6, 2015 under Executive compensation, Pay for performance |

Time to turn in your papers

Today was the last day of the comment period for the SEC’s proposed disclosure rules on pay-for-performance. My own submission offers a few relevant points:

1. There are two reasons why investors would care about pay-for-performance: (a) to judge compensation cost and (b) to judge alignment of interests between managers and owners.

2. The SEC proposal does injustice to the first reason, and completely ignores the second.

3. As a result, the proposed disclosure will create a potentially, grossly distorted view of pay-for-performance.

4. If the SEC wants good disclosure on this matter, its requirements must acknowledge the investors’ perspective with some significant changes (which I propose).

5. If they can’t or won’t make those changes (and they probably shouldn’t at this point), the SEC should revert to a principles-based disclosure, and let the market sort out whatever resonates with investors.

I consider this rule one of the most important that the SEC will devise this year. In the long run, pay-for-performance disclosure will have far more impact than the more controversial rules on CEO pay ratios and compensation clawbacks. If the disclosure rule ends up close to its current form, it could be just one more nail in the coffin of public companies.

Posted by Marc Hodak on June 15, 2015 under Executive compensation, Governance, Invisible trade-offs, Unintended consequences |

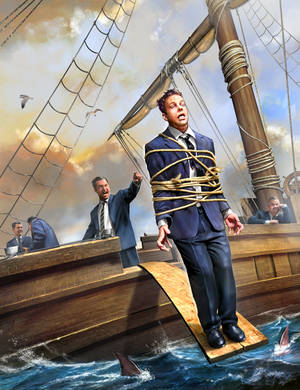

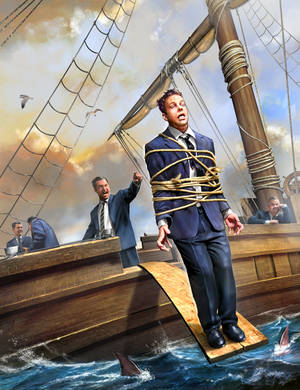

Hey you out there: Just kidding

Let’s say that you hire a captain for your ship, and for, say, tax reasons, decide that instead of running things from the bridge he should run things from the plank. You warn him that if anything goes wrong, he goes into the drink. But rough weather comes along, and you decide you still need him, so you don’t push him over the edge. At this point, you’ve hurt your credibility and pissed off the sharks.

That appears to be what is happening as activist investors increasingly get into the game of second-guessing corporate bonus plans. On the plus side, these shareholders are digging much deeper than the typical, diversified institutional investor possibly could. Marathon Partners, for instance, is criticizing Shutterfly’s plans that reward growth without assurance that it is value-added growth, which looks like a valid criticism.

But that doesn’t mean that activists investors necessarily know more than the boards they are criticizing:

Jana Partners LLC, which recently took a $2 billion stake in Qualcomm, has urged the company to tie executive pay to measures like return on invested capital, rather than its current yardsticks of revenue and operating income, according to a Jana investor letter. Such changes “would eliminate the incentive to grow at any cost.”

Yes, it would. But return on invested capital could instead create the opposite incentive, i.e., a bias against value-added investment. (If the investors really knew what was what, they would more likely require economic profit as the compensation metric.)

Although companies should generally be given the benefit of the doubt about their plans, they don’t do themselves any favors by trotting out the specter of retention risk when discussing variable compensation. Yet we often hear companies say, or using code words to the effect of, “Hey, we have to be careful that our incentive plans aren’t too tied to performance, because if they don’t pay out, we might lose key talent.”

Notice to Corporate Boards: Nobody buys this explanation.

And, by the way, if your variable compensation plan creates retention risk when it doesn’t pay out, then your compensation program is too weighted toward variable instead of fixed compensation. In other words, your salaries are too low and your target variable compensation is too high. In a well-designed plan, salary should cover the minimum amount of pay that would be needed to keep your executives around when your company is performing poorly.

Alas, too many corporate incentive plans are poorly designed, but not for the reasons usually toted up. These plans are a mess because the most important incentive of all is the incentive created by Section 162m of the tax code to underweight salary and overweight variable compensation. That puts public companies in a bind when incentive plans don’t pay off, which is clearly (and predictably) a recurring problem.

In other words, companies may be wrong-headed for conflating alignment issues with retention issues when arguing for slack in their bonus plans, but they come by this wrong-headedness honestly; it is a logical reaction to the unintended, deeply perverse encouragement our tax laws.

Fortunately, an increasing number of companies are starting to ignore the 162m salary limits. They are realizing that the harm that higher salaries may cause their shareholders in the form of higher taxes is easily outweighed by the benefits of more rational ratio of fixed vs. variable compensation for their management, one that militates against the real retention issues that too much compensation risk might cause.

Posted by Marc Hodak on June 2, 2015 under Executive compensation, Governance, Revealed preference |

The unanticipated death of a public company top executive can often create an observable market reaction. Sometimes, this reaction is not flattering, as when the stock price jumps five to seven percent when a CEO dies because there was no other way for the shareholders to get rid of him.

On the other hand, you get examples of what happened when the market was hit with news that Ed Gilligan, American Express President and heir apparent to the CEO, passed away suddenly on Friday. Amex stock dropped about ten cents per share (after accounting for changes in the market overall)—a drop of about $100 million dollars. Which answers the question posed in this title: Yes, some people are clearly worth to their shareholders what they are being paid.

Ironically, this financial hit was the result of good governance. Amex did what it was supposed to do in clearly identifying a likely successor in case they should suddenly lose their CEO, as well as pave the way for his retirement. The value of clarity about successorship is supported by empirical evidence. So, in a sense, what Amex has lost in a worthy successor, besides whatever else Gilligan uniquely provided to the company, was simply giving back what they had previously gained from doing the right thing in establishing a clear heir to CEO Kenneth Chenault.

And now Chenault, who just lost a close colleague for whom he clearly had great affection, must once again groom another successor.

Posted by Marc Hodak on June 1, 2015 under Unintended consequences |

Choices, choices

Why are drug costs are so darn high? This perennial question was once again raised at an annual medical meeting by Dr. Leonard Saltz, a senior oncologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering. He contended that newer combination cancer drug treatments costing almost $300,000 are simply not sustainable. Dr. Saltz mentioned one possible contributor to the high costs sure to excite those of us who catalogue perverse incentives:

He…called for changing the way Medicare pays for infused drugs. Doctors currently receive a percentage of the drug’s total sales price. The payment method has created a conflict of interest because cancer doctors can make more money by using the most expensive drugs, he said.

If you believe, as I do, that drug companies should make money on drugs, and doctors should make money being doctors, then the idea of doctors making money selling drugs sounds suspicious. It’s easy to be wary of brokers in any field–real estate, investments, executive search–where their income is based on how much you pay for the things they are recommending; ergo, a conflict of interest. Each of the aforementioned brokers would argue that their interest in getting a deal done as quickly as possible easily trumps getting the highest possible price, and they would have a point.

Doctors can’t say that; they don’t need to create a sense of urgency for cancer treatments. Read more of this article »

Posted by Marc Hodak on May 14, 2015 under Governance, Revealed preference |

Whoa.

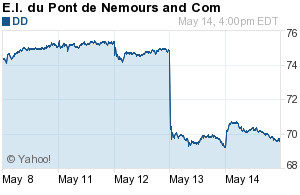

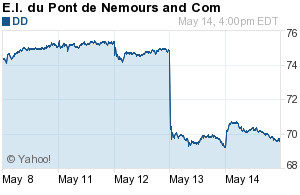

Those who have followed the Dupont/Trian contest know that the shareholders voted (barely) to retain the incumbent board. But two other, fascinating pieces of information are apparent from the aftermath of that vote regarding the investors’ reaction:

1. The market was surprised

2. The market was disappointed

A seven percent drop in the stock price is huge. Shareholders were clearly invested, so to speak, in seeing Trian win, even as they voted them down. So, while shareholders-as-voters accepted CEO Ellen Kullman’s explanation that Nelson Peltz does not know as well as she what is best for their company, shareholders-as-traders said, “Whoa, that was a terrible decision!” We assume that, being the same people, each making their judgments based on their individual, independent estimation about the future prospects of the company, and with the “wisdom of crowds” sorting out their discordant judgments into a useful, single verdict, we should see less schizoid outcomes.

Alas, this “crowd” effect works via very different mechanisms in proxy voting versus in market pricing. So, which result should management heed? Read more of this article »

Posted by Marc Hodak on May 3, 2015 under Executive compensation, Governance, Pay for performance |

The SEC has released proposed rules for disclosing pay for performance, based on the Dodd-Frank law requiring that each company provide “information that shows the relationship between executive compensation actually paid and the financial performance of the issuer, taking into account any change in the value of the shares of stock and dividends of the issuer and any distributions.”

As my regular readers know, “pay for performance” can be usefully evaluated only when we have appropriate definitions of “pay” and “performance.” Appropriate definitions depend on one’s purpose for making the evaluation. Pay-for-performance can be either an exercise in costing, i.e., seeing if shareholders are getting what they are paying for, or for determining alignment, i.e., seeing if management rewards are consistent with shareholder value creation. These can be different analyses, with the same underlying figures yielding very different conclusions.

Read more of this article »

Posted by Marc Hodak on April 26, 2015 under Executive compensation, Pay for performance |

If you are a corporate director, you might not know that executive compensation at your company is now being evaluated, in part, based on your economic profit (EP). The people doing these evaluations are any of the over 300,000 security analysts with access to the new Bloomberg Pay Index, a daily ranking of executive pay for performance (discussed here by Bloomberg’s Laura Marcinek), This index provides a compensation efficiency score based on the ratio of total pay against EP. For instance, Tim Cook—highlighted by Bloomberg as the best CEO bargain—had 2014 pay of $65 million, which was just 0.2 percent of Apple’s three-year average EP.

Two things stand out about this index. First, these data are directly available to the analysts—many of whom are skeptical of the quality of current proxy advisor recommendations—without the intermediation of their governance groups that may be advising them on their proxies. So, this index is likely to have some impact on proxy voting.

Secondly, this index will underlie an increasing number of media reports on compensation governance. It is already behind a stream of articles commenting on pay for specific executives.

What is truly revolutionary about this index is the EP performance metric Bloomberg uses in determining pay for performance. This use of EP represents a breakthrough for three reasons: Read more of this article »

Posted by Marc Hodak on April 21, 2015 under Executive compensation, Reporting on pay |

Uh, there are no jelly beans in this jar?

James Surowiecki, author of the bestselling “Wisdom of Crowds,” recently penned an article in the New Yorker called Why CEO Pay Reform Failed, regarding the Dodd-Frank mandated “Say-on-Pay” rule.

He correctly notes that Say-on-Pay has, against the hope of its proponents, done “approximately zero” to stop the rise in CEO pay, and that shareholders have almost universally endorsed these pay levels with overwhelming support. He offers some reasons:

“Why have the reforms been so ineffective? Simply put, they targeted the wrong things. People are justifiably indignant about cronyism and corruption in the executive suite, but these aren’t the main reasons that C.E.O. pay has soared. If they were, leaving salary decisions up to independent directors or shareholders would have made a greater difference. As it is, studies find that when companies hire outside C.E.O.s—people who have no relationship with the board—they get paid more than inside hires and more than their predecessors, too. Four years of say-on-pay have shown us that ordinary shareholders are pretty much as generous as boards are. And even companies with a single controlling shareholder, who ought to be able to dictate terms, don’t seem to pay their C.E.O.s any less than other companies.”

In other words, the very things that people are “justifiably indignant about” appear, in fact, to not be justified. But he is writing in the New Yorker where indignation about CEO pay is a matter of religion, so Surowiecki has to find something, anything, to justify it. He concludes that:

(a) Boards of directors are deluded in thinking they can actually distinguish CEO talent, and are thus irrationally paying more for talent they cannot discern, and

(b) Investors have been hoodwinked by an “ideology” that CEO talent is rare, and that higher rewards can lead to better CEOs. (In other words, maybe certain crowds aren’t that smart.)

If this seems like more than a bit of reaching, consider his sources. Read more of this article »