Posted by Marc Hodak on October 28, 2016 under Governance, Scandal, Self-promotion |

This week, I was a talking head on CCTV‘s The Heat with Anand Naidoo. I was brought in to comment on how poorly implemented corporate incentives could lead to the kind of scandals we have seen of late, e.g., Wells Fargo, Mylan, and VW. Being an expert on incentives and corporate scandal, it seemed like a good place for me to contribute. I believe that was also the impression of Richard Bistrong, who is an expert on corporate corruption and compliance.

Unfortunately, the interviewer instead peppered us panelists with questions about the corrupt relationship between business and politics. I was not entirely comfortable about that direction, not because I don’t have well-supported opinions on that topic, but because it just wasn’t what I was prepared to talk about. So, I kept trying to bring it back to corporate incentives, with modest success. (They cut my comment that, hey, I was a governance expert, not a political commentator.) I was ultimately able to make a few key points:

- Perverse incentives were at the root of a number of the scandals

- Those incentives are widespread in corporate America

- It’s getting harder for public companies to monitor internal bad behavior by virtue of their increasing size

My one acknowledgment of the politics was to counter one of the comments by the far-left lobbyist they brought on as a third panelist. He suggested (several times) that Obama’s DOJ and SEC failed to do their job of wholesale jailing of bankers and executives because government prosecutors were involved in some sort of concerted effort to not prosecute criminals, what I called a reverse conspiracy theory.

Being relatively new to TV, I learned that my habit of looking up for a moment as I think about what to say may look a little shifty on camera. Need to keep my focus on the lens.

Posted by Marc Hodak on October 23, 2016 under Invisible trade-offs, Scandal, Stupid laws |

In the History of Scandal class that I taught in the mid-2000s, one of the lessons was that scandals have a life of their own, separate from the reality that they are nominally attached to, with the reality invariably being much less salacious than the stories that grew up around it. I have since seen the opposite phenomenon, as well–stories that could easily be made into huge scandals, but simply make the news one day to die the next.

In that context, I find myself asking, why isn’t New York’s attempt to outlaw Airbnb a scandal? The ban, and the now accompanying fines of thousands of dollars, is designed to restrict apartment owners from renting out their apartments to visitors. This has several obvious effects:

- Restricting the number of rooms available to visitors from out of town

- Making hotel rooms more expensive, so that the visitors that do come have less to spend on non-hotel items

- Preventing generally less affluent apartment owners from adding to their income (rich people don’t need to rent out their apartments to make ends meet)

But it should not be surprising that the bill was not called the “NYC Visitor Cap Bill,” or “Only Rich Visitors Allowed Bill,” or the “Ordinary Apartment Owners Don’t Really Need Extra Income Bill,” or the most honest title, “Government Supports Hotel Owners and Unions Bill.”

Read more of this article »

Posted by Marc Hodak on October 15, 2016 under Economics, Executive compensation, Governance |

Bengt Holmstrom, a co-winner of the 2016 Nobel Economics Prize, rails against the complexity of executive pay. He’s right about that. He blames compensation consultants, but that is attacking a symptom, not a cause. The underlying cause is the proliferating regulation—formal and informal—of compensation governance. This regulation creates constraints on how Boards can design executive compensation programs. Boards rationally react to those constraints by building plans of ever-greater complexity.

The source of compensation regulations is popular disdain for high CEO pay. The intent of the regulations is to tamp down that pay, but that’s like putting nails in a board to stop a marble from rolling down. You don’t stop the marble; you just make its path more complicated.

Nevertheless, Prof. Holmstrom is a worthy scholar, one whose research has done much to inform my discipline, even if unfortunately few practitioners have actually heard of him, or heeded his conclusions.

Posted by Marc Hodak on August 1, 2016 under Executive compensation, Pay for performance, Reporting on pay |

If that seems like a silly question, then you would would have reacted as I did to the headline, “Does Higher CEO Pay Produce Better Company Performance?”

The MSCI research cited in the article states:

A report by MSCI sampled 429 large-cap U.S. companies between 2006 and 2015. It found that during that time, shareholder returns of those companies whose total pay was below their sector median outperformed those companies where pay exceeded the sector median by as much as 39%.

If one’s concern were the governance implications of that conclusion, the headline should have read the other way around: Does better company performance result in higher CEO pay? This question gets specifically at alignment between shareholders and CEOs. The MSCI study clearly answered that question as “no.”

The author of that study, Ric Marshall, concluded that companies ought to be more careful in how much equity they grant, since that was the biggest source of total compensation among the CEOs, and in their variation in pay. Mr. Marshall has a point, but for a different reason than one can conclude by looking at pay as reported in public disclosures.

The problem is not the amount of equity per se, but how equity is granted. A company has to pay its CEO enough to be competitive. If it didn’t pay in equity, it would have to make up for it in cash. The advantage of equity as a pay instrument is its residual ‘alignment effect’ after it is granted.

So, from a competitiveness standpoint, when the stock price is high, you can grant less equity (i.e., shares or options) in order to provide a given value of pay. When the stock price goes down, you have to grant more equity to remain competitive. When the stock price plummets because your company underperforms, and you subsequently feel you have to grant a lot more to remain competitive, and then your stock price recovers, your CEO will end up with a lot more award value than the CEO of a competitor whose firm’s stock price dropped much less, before also recovering. And voila, the poorer performing company ends up with a higher paid CEO.

MSCI looked at the 2006 – 2015 period for its study. This period corresponded precisely to the peculiar rollercoaster scenario noted above.

In other words, equity behaves differently than cash, both in how it is granted as well in how it is realized. Grant values and realized values interact with the price of the stock, and those interaction effects can easily lead to mis-alignment.

The solution is not just to grant less equity, as Mr. Marshall suggests; that might not satisfy the need for competitiveness. The answer is to pay executives in a way that doesn’t penalize good performance, or reward poor performance. There are ways of doing this, but it requires boards that are willing to look at more than “what is everyone else doing today” in designing their incentive plans.

Mr. Marshall offered another suggestion, that disclosure rules begin to look at pay over a longer time frame, i.e., the tenure of the CEO. This would get rid of most of the idiosyncratic pay elements, especially those that surround hiring and departure that screw up attempts to compare pay and performance year-by-year. I think this is a very good suggestion.

Posted by Marc Hodak on April 28, 2016 under Governance |

I’ve been hearing a lot of angst about Facebook’s decision to issue a new class of non-voting shares for the express purpose of preventing dilution of Mark Zuckerberg’s control over Facebook. Mainly, the complaints are of the nature, “It’s undemocratic!” The best response I can offer: Get over it.

God did not ordain that all companies need to be governed in any particular way. Yeah, I get the benefits of a more diverse shareholder influence over the board. I get that he might abuse the outsized authority he has gained from dual class (now triple class?) shares, and act in ways that hurt minority shareholders. I would be willing to grant all that and ignore that Zuckerberg’s influence has so far been very beneficial to all shareholders, and that his board is as good as one might hope for to restrain his potential excesses.

But here’s the deal with Facebook: Zuckerberg is in control. Every current shareholder bought into that premise. There is no moral principle that says we need to adjust the charter or capital structure to accommodate our personal or collective preferences on what “good governance” ought to look like after the fact.

What about the fact that Zuckerberg has now added another layer of anti-dilution protection that wasn’t there when current shareholders bought into Facebook? Well, they bought into that, as well. They bought into the current change insofar as Facebook is, basically, the charter that enables that change and everything else that Facebook is. When you date a paranoid, you can’t complain when they add another alarm system to the house.

If you’re an outsider and don’t like the change, then don’t buy into the Zuckerberg-controlled Facebook. If you’re a shareholder who feels that he has somehow changed the relationship between you and him as shareholders, then sell your shares and pocket the gains.

I get that one day Zuckerberg might get stale, and we’ll wish he didn’t have so much control. You can sell your shares then, or in advance of that time, based on some suitable discount horizon. None of us is entitled to the kind of corporation we wish we had; we’re entitled to the corporations we buy into, warts and all.

As usual, the people most agitated about this are the governance mavens with a knee-jerk reaction against anything that undermines shareholder democracy. They react as if shareholder democracy equates to shareholder-friendly governance, notwithstanding any actual evidence to support that. Shareholders should, instead, celebrate the diversity of governance structures out there, make their bets on governance structures, as well as strategy and people everything else bundled into their bets, letting the market sort it out, and letting entrepreneurs focus on business rather than shareholder relations.

Posted by Marc Hodak on April 15, 2016 under Uncategorized |

Some of the happiest moments of my life were spent with Levend Beriker, my partner, my friend, my kindred spirit. Many of our moments come back like snapshots from another era:

- Standing at the railing of an outdoor bar after work, overlooking the Bosphorus, the lights from the Asian side dancing on its waters;

- Dining at a sidewalk table on the Upper West Side, talking about clients and kids and, in our single days, the women walking by;

- His smiling face as he walked toward me on a Mediterranean beach, announcing that he did a bungee jump that, just an hour earlier, he said would be nuts to even contemplate, and which he promptly talked me into;

- Having a beer with my parent’s on their Maryland deck when we were each visiting the D.C. area; my mom, a French-Moroccan Jew who maintained her home as a mini-U.N., loved that I had a Turkish partner, and such a fine one, at that.

It occurs to me that these particular snapshots are now twenty-year-old memories. In that period, we were single fathers of two young children (each) being raised on separate continents. Levend once suggested that we should rent a sailboat with crew and provisions for a five-day cruise with friends and family. I laughed that we could toast each other like Murphy and Ackroyd at the end of Trading Places: “Looking good!” It became our favorite toast whenever we celebrated new clients.

Then there is the snapshot memory of us meeting at the airport in Prague where we had decided, just days before, to converge and take in the sights. In one of those overpriced cafes on the Old Town Square, Levend told me he had met someone special. The impending denouement of his bachelor days no doubt prompted me to get more serious about the women I was meeting, or risk being left behind. So it is probably no coincidence that less than three months hence, I too would meet my future wife.

Next came his simple, gorgeous wedding in Victoria to Shannon, the love of his life. This memory seems more like a short film than a snapshot, me and my girl soaking in the Victorian charm of those magical days. A couple of years later, our reconstituted families were playing and dining together in Istanbul and in Kemer, the wooded community where Levend and Shannon lived.

And here is a literal snapshot of Levend, joining me and Stephan on a boat for an impromptu meeting on Lake Lucerne. I can’t recall the confluence of fortune that led us to this particular place. Levend seemed preternaturally prone to serendipity in his life, and, among his great gifts, taught me to embrace it in mine.

Levend and Shannon eventually moved to their little paradise in Victoria. With both of us in North America, we expected to see more of each other. But that didn’t happen. Levend’s transition from Turkey to the West Coast, and from our brand of client consulting to his new frontier of SAAS development, went a little slower than hoped, forcing him to divide his time between Canada and Turkey, making our personal (as well as business) interactions even scarcer.

After my wife and I bought our ranch in Texas, and began dividing our time between New York and Dallas, all my conversations with Levend were via phone and e-mail, always ending with “Let me know when you’re in New York” or “When are you coming to Victoria/Dallas?” For reasons best understood by working people who haven’t yet lost a best friend, we assumed that we would have a very long time to realize many such visits, even as the years slipped by.

One night last year, when Theresa and I were at a rooftop bar in New York, the surroundings inevitably had me thinking about Levend. So I dialed him up on FaceTime to tell him that I was missing him. I panned the phone across a scene of young professionals milling around with drinks, a scene that we had once so often inhabited. Levend nodded and smiled, then panned his phone to show an even more familiar sight–a plane full of passengers.

To the very end, I was actively working to get Levend meetings with Dallas banks to sell his new service, and of course to have an excuse for him to visit us at the ranch. I know he would have loved it, as we would have loved having him. We could have sat on our back porch beneath a big Texas sky, surrounded by woods, a small waterfall spilling into our pool, raising our glasses and saying “Looking good!”

I will miss him terribly.

Posted by Marc Hodak on April 11, 2016 under Governance, Politics |

Democrat senators, the folks lamenting the hyper-politicization of certain Presidential appointees, have turned on President Obama’s nominees. They are simply refusing to fill out the short-handed Securities and Exchange Commission until the nominees pledge to implement a requirement that all corporations submit their spending to public scrutiny. Senator Schumer is one of the peeved politicos:

Schumer said the nominees are “fence-sitting” on whether to force corporations such as Koch Industries to reveal their political giving.

Keep in mind that Koch Industries is a private company, nominally beyond the SEC’s power to force disclosure. That’s how crazy the discussion has gotten regarding regulating political spending.

Why do Senators, particularly Democratic Senators, care so much about this one issue that they would stymie a Democratic President over it? Forget all the bogus arguments about whether corporations are people, or whether money is speech, etc. The basic fact about political spending is this: incumbent politicians want to control it. The first step in controlling it is knowing about it. The old knowledge that money is power is particularly apt when it comes to politicians knowing who you are supporting, and how much you are giving them. Congress wants not only the power of the purse, they want the power of everyone’s purse. And they get to go for it by decrying greed.

Some Republican politicians are happy to conspire to limit spending on political causes because all regulations on political activity inherently favor incumbents. One of the great, under-reported ironies of the last decade was Senator McCain losing a presidential election because candidate Obama felt he could do better outside of the McCain-Feingold restrictions while candidate McCain was compelled to comply with them.

Since Democrats have an overpowering inclination toward controlling everything, their push to control political spending is much more aggressive. Dodd-Frank mandated that the SEC write rules regarding corporate political spending, but it was one of hundreds of rules, and the SEC is way behind in writing them. And they can’t catch up with just three commissioners. So, the best thing is to let the Democratic-dominated commission get on with its business, right? As Senator Warren has said:

President Obama has done his job – sending…nominees to the United States Senate. Now it’s time for the Senate to do its job.

And as Senator Reid has said:

The American people expect their elected leaders to do their jobs. President Obama is performing his Constitutional duty. I hope Senate…will do theirs.

Actually, what Reid said was that Senate Republicans should do theirs, referring to the President’s appointment of a Supreme Court judge. Senator Warren was also referring to the President’s Supreme Court appointment, but is now one of the ringleaders in stifling the President’s SEC appointments based on the single issue of political spending.

Of course, Senate Democrats don’t own hypocrisy in Congress. But, if they are willing to block nominees, including the exceptionally well-qualified Lisa Fairfax (a brilliant legal scholar that I don’t always agree with), then they have thoroughly given up any high ground with regards to Senate duties and with respect for the Executive.

Posted by Marc Hodak on April 5, 2016 under Collectivist instinct, Politics |

The Obama administration stunned the business world yesterday with new, draconian rules designed to prevent so-called tax inversions. Inversions allow American corporations to escape most U.S. income taxation. The animus against such inversions is emotional and financial. On the one hand, companies wanting to leave are accused of being ungrateful, unpatriotic, insidious, or worse. In other words, the rationale against inversions is an appeal to emotion. But the real driver of that antipathy is that their escape from U.S. taxation creates a bigger tax burden for the rest of us. I believe that if the money weren’t the issue, the emotion wouldn’t be there.

Not too long ago, America was the destination of choice for individuals and companies. I don’t recall any of this emotion in reverse. America has accepted foreign investment, including wealthy foreign individuals and foreign companies wanting to domicile here, with open arms. In fact, these types of immigrants were considered America’s due for being the freest, most business-friendly nation on earth. We would have regarded the idea that they were “economic deserters” with respect to their home countries as bizarre or unhinged. America has generally accepted foreign individuals much more grudgingly and with suspicion, but we never thought of immigrants as wronging their country of origin just for leaving. Neither did their former compatriots, with one exception.

Read more of this article »

Posted by Marc Hodak on April 3, 2016 under Governance, Regulation without regulators |

Regulators are finally looking at unicorns–private companies grown to over $1B–and all they see are unbridled horses. SEC Chairwoman Mary Jo White is bothered:

White echoed the concerns of some industry insiders that these tech start-ups are missing out on the market discipline public companies receive by being accountable to the whims of public shareholder. (sic)

And on top of losing out on the whimsy, White adds:

For these companies to be successful, investors must be confident that they are being treated fairly and that companies are being transparent.

That these things were written without irony shows how unmoored our discussion of corporate governance has gotten from reality. Clearly, the poor investors of Uber, Airbnb, and Snapchat must be slapping their foreheads, saying “THAT’s why success has eluded us! We need more SEC oversight!”

I’m sure the good governance mafia (GGM) will accuse me of being tone deaf with regards to the benefits of greater SEC oversight of these giant, private firms. Clearly I don’t get that without an additional two thousand pages of rules, these companies would just do whatever they want, and their shareholders would suffer. Because cheating your shareholders is how you build great businesses.

Here is an alternative view, one I recently shared at a major economic forum:

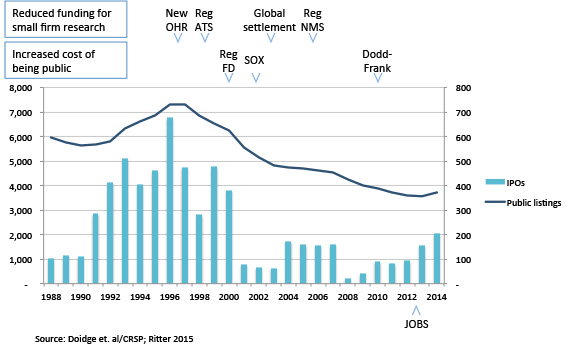

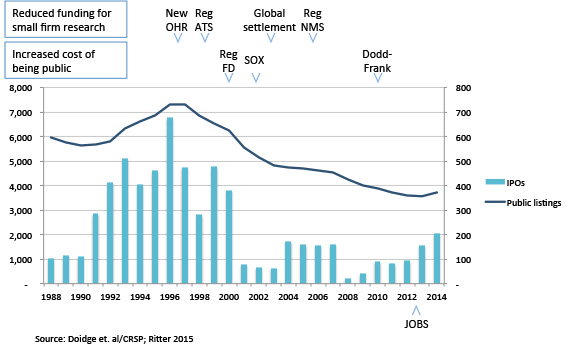

This chart shows some of the regulations that have multiplied the costs of being a public company over the last couple of decades. Yes, it’s possible that something other than these escalating public company costs led to the collapse of the IPO market. It’s possible that something other than these escalating public company costs have contributed to the dramatic decline in public companies. You have endogenous factors, omitted variables, and all that stuff. I understand.

But people who inhabit the executive suites, board rooms, and trading floors don’t need this chart to tell you what happened, especially those who grew up in the ’80s and ’90s when “going public” was the epitome of success. They will tell you that the costs of being public now outweigh the benefits for all but the largest firms. They know that a bad cost-benefit trade-off is not good for shareholders, regardless of what self-appointed “shareholder advocates” might say.

Admittedly, this all sucks for the average retail investor. Those without the net worth to be allowed to invest in private equity or venture capital opportunities are now cut out of a fast growing, lucrative market. Many of these same retail investors belong to public or union pension funds that have agitated for this two-tiered capital market, where the rich have more choices than average workers.

The SEC has long left sophisticated investors alone precisely because they need the least protection. The private companies that have these investors on their boards are presumed to be adequately governed. Yet we now have a top regulator telling some of the winningest companies on earth that they are losers for not joining her club.

Posted by Marc Hodak on January 4, 2016 under Governance, Self-promotion |

I will be explaining why the public company universe has become much more concentrated in the U.S., how private equity is filling the breach on growth and innovation, and what it means for the future of management:

Also, the dangers of using financial accounting for managerial decision making. It’s a double-header.

If you’re a finance type in Dallas next week, stop on by. I promise a good show.