Posted by Marc Hodak on April 8, 2008 under Politics |

Politics is about finding meaning. That’s probably why I have such a difficult time with politics. For instance, I have no idea what this means (from an AP story about Hillary’s reaction to a McCain comment):

“I fundamentally disagree,” Clinton said, reading from prepared remarks that aides said she wrote.

Does this mean that Clinton disagreed? Or that she read her disagreement from prepared remarks? Or that she wrote those remarks herself? Or that aides said she wrote them?

I’m assuming there are actually editors working at the AP. If this is edited copy, one must assume there is something more to this statement beyond the nominal quote. Someone, please help me out, here.

Posted by Marc Hodak on April 7, 2008 under Executive compensation |

Many CEOs over the years have reportedly turned down bonuses or otherwise requested that they get less cash than the Board approved in their pay packages. This act generally invites praise or cynicism of the CEO. As far as I’m concerned, once the board has awarded the money to the CEO, he or she can do whatever they want with it, including return it to the company, pass it along to their colleagues, or donate it to my kid’s education. However, I’m always left wondering about the governance of companies that have somehow accidentally paid their CEO too much.

Generally, the refusal to accept the full board-approved pay is associated with poor company performance. Foregoing pay is generally intended to be a sign that the CEO wishes to “share the pain” of cutbacks being felt by the workforce or declines suffered by the shareholders. This sacrifice is generally well received by the employees when it’s donated to a pool to be divided by employees. It’s often well-received by the shareholders when the CEO simply allows his bonus to revert to the corporate coffers. Sometimes, the CEO gives back cash, but gets more in equity, something the unions refer to as “bait and switch,” and what we at the HV Mechanism Design Center refer to as a poorly implemented incentive plan.

In fact, my problem with CEOs turning down pay has nothing to do with their motivations around what they or others feel they deserve. My reservations are about their boards’ competence in incentive design. A well designed bonus plan should never result in a situation where the CEO doesn’t feel his or her pay is undeserved. A well-functioning board should not find itself in a position to have its incentives ignored and returned. What impact did the incentives have if the CEO didn’t even take it?

A CEO dictating to the board to give them less than the board approved does not inspire confidence in me that the board is in control over one of the few things they should totally control. Whether the CEO does this out of a sense of guilt or showmanship or political correctness does little to salve that concern.

Posted by Marc Hodak on April 6, 2008 under Self-promotion |

Right about now, high school students across the country are getting their verdicts on where they were admitted, or not. For the hundreds of thousands who were applying to selective institutions, this is the last stage of a decision making process that began last summer. This process included decisions about which schools to apply to, early versus regular applications, financial aid considerations, etc.

As one can imagine, any tool that can bring a little sense of control to this grind is a welcome help. My older guy, Max, came up with just such a tool. College Admissions collects information from users (i.e., a college applicants), and returns some user-specific information to help them decide where to apply and their odds of getting in. Max used a proto-type of this system to get into Duke. As with most things in this Internet Age of network effects, the more people who use this tool, the better it works, and the more it spreads. Thousands of students have already used College Admissions in applying for the upcoming freshman year, offering a lot of positive feedback.

Those of us with high school juniors know that the process is just beginning for a whole new round of kids. If you know kids ready to start down this road, especially they are on Facebook, they will probably encounter this application. But feel free to send this link to them, anyway: http://app2.collegeproject.net/. That way, when you wish them good luck, and they will at least know what their odds are!

Posted by Marc Hodak on April 3, 2008 under Regulation without regulators |

I just got back from my annual teaching visit in Switzerland. I left for Zurich earlier this week, soon after finishing an article I had written for Forbes about the governance challenge of ‘utopia.’ I wasn’t thinking about Switzerland when I wrote the article, but I was thinking about the article soon after I arrived there. One of my points in the article (hopefully coming out soon) was that it’s dangerous to invest utopian hopes in any particular leader; if they don’t disappoint you during their reigns, you will surely be disappointed by their successors. This is a useful lesson to remember during our frenetic presidential campaign, where it seems everyone is looking for a hero or a savior, and the candidates seem happy to play the part.

While riding a quiet train past Swiss villages, the titular question came to mind. I would guess that most people who read this, and others like you, can name the British Prime Minister, French President, and German Chancellor. But no one knows the president of Switzerland. To be sure, the heads of the larger European countries are very powerful individuals, and their nations have far more vigorous foreign policies, which keeps the names of their leaders in the press with some frequency. That’s my point.

Switzerland is among the most peaceful and prosperous nations on earth. But I’ve never heard of any Swiss president, let alone one leading this or that crusade. It seems to me that there is a relationship between those facts.

Posted by Marc Hodak on March 30, 2008 under History |

I just hope she isn’t in some gulag after this:

More here.

HT: an uncredited reasonoid

Posted by Marc Hodak on March 28, 2008 under Invisible trade-offs |

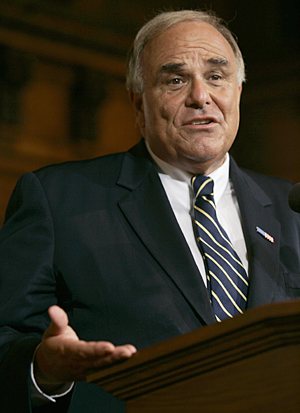

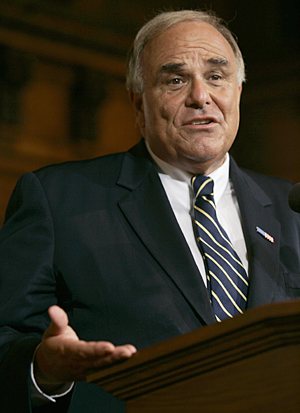

Governor Ed Rendell of Pennsylvania, that is. We’ve never hung out, but the Governor strikes me as a decent guy. He’s caring, intelligent, and has a sense of humor. His economic literacy, I’m not so sure about that.

Governor Rendell devoted his entire talk last night discussing our infrastructure. He noted that Pennsylvania and the rest of the nation are suffering horribly from deferred maintenance. He had the numbers to prove it. Good enough. But, there was one point he repeatedly brought up:

The states can’t do it alone. The states supply 75 percent of the spending on infrastructure, but it’s not enough. Ours is the only federal government among the wealthy nations that does so little for its infrastructure. The federal government has to be part of the solution.

So, I asked him:

Governor, isn’t that saying that the taxpayers of Pennsylvania should pay for infrastructure in Alaska, and taxpayers of Alaska should be paying for infrastructure in Pennsylvania? That bargain hasn’t worked well for Pennsylvanians in the past.

It was two questions, really. The first asked why he supposed there would be more money from the taxpayers collectively than there is from the sum of them individually. The second asked what benefit there was by taking the same pool of money and funneling it through Washington, D.C..

His answer to the first half would have been shocking if it didn’t come from a politician: “The federal government can always find the money.” That’s right, he literally said “find.” The money is out there, the government simply needs to “find” it. Nobody in the room who heard this non-answer seemed surprised. His answer to the second half was barely better: “We’d need to insure accountability in the distribution of such funds via a panel of experts.” We know how that works out.

Posted by Marc Hodak on March 27, 2008 under Practical definitions |

In Jared Diamond’s excellent book Guns, Germs, and Steel poses a question via the mouth of a Papuan native: “Why do you have so much cargo?”

“Cargo” is a native word for ‘stuff,’ as in the kinds of goods commonly produced by an advanced society. Every primitive culture that has come into contact with an advanced civilization for the first time has shared an understandable awe at the explorer’s (or invader’s) ‘cargo’–from their explosive armaments down to their metal shoe buckles.

Now, a civilized person might assume that natives faced with ‘cargo’ might try to understand how it was made so they might begin to build approximations of it. But that would reflect the civilized person’s naivete. In fact, primitive people commonly endow things with a mystical property that goes beyond its form or function. For them, everything is guided by a higher spirit, a spirit may send the cargo their way versus toward someone else.

Down that mystical path, natives will begin engaging their existing theories about what moves the spirits, and begin to exhibit what, to us, looks like strange behavior to persuade the spirits to drive cargo their way. This is called a cargo cult.

Civilized people look upon cargo cults with a sense of wonder and amusement. We shake out heads at shirtless people dancing and praying to their version of Gaia, as if that might somehow make a washing machine appear. Civilized people would never do that.

Posted by Marc Hodak on March 19, 2008 under Revealed preference |

On our way back from dropping our big guy off at college, we looked at schools with our little guy. (We call him the “little guy” although he’s now the biggest member of the family.) We looked at a cross section of schools–big, small, public, private, urban, rural, etc. His verdict was in favor of bigger, small-town campuses. UVA scored well on these criteria.

We also figured out on this trip that New York kids apply in out-sized numbers to schools in the mid-Atlantic. Why? The obvious answer is that there’s lots of us. The more complete answer, especially when faced with paying private school rates for public schools (a.k.a., out-of-state tuition), is that many state schools (UVA, UNC, Maryland, etc.) are pretty good. SUNY, on the other hand, is among the worst systems in the country. New York state should be ashamed of itself, but then I know what New York politics is like, and shame is not part of the equation.

We also got some more insight into how the average kid chooses a college, even though this is our second student. One has in-school and on-line resources to help determine the appropriate criteria for choosing. One has publicly available judgments of various institutions along the dimensions of those criteria. And stuff. In the end, it seems to come down to reputation and physical attractiveness. And, of course, by that little thing we know of as admissions. And maybe who gives you money to offset those outrageous tuitions. (College or a new house?)

Posted by Marc Hodak on March 14, 2008 under Invisible trade-offs |

Most people are against earmarks, it seems, except those who dish them out.

The political logic of earmarks is impeccable. If you’re a Congressman or Senator, there’s this big pot of money on the table. If you don’t reach into it, others will, and will leave you with nothing. Do you want to be Congressman Can’t Bring Home the Bacon? Individually, congressmen may largely agree on the idea of getting rid of pork barrel spending. It would actually make their jobs easier, more ennobling even, to focus on the bigger issues of state than who should get what from the public trough. But the people with the power to change the system are the ones who benefit the most from it. They have the most control over the pork. They are the most adept at using that pork to maintain their power. They indeed grew up in this system of power for money, and frankly wouldn’t know what to do if it were drastically changed. So, earmarks are ingrained in our politics.

The economic logic against earmarks is just as impeccable. When a congress-critter proclaims that they secured $500,000 for a new Teapot Museum, their constituents may be thinking, “Do we really need this?” But what many of them are also asking is, “How much money did I send to Washington? If I’m getting this little part of it back, why didn’t they just let me keep it and spend it?” In other words, there is probably little to be gained from my congressman spending my tax dollars on some private benefit for me. I’m perfectly capable of paying museum admission, if I’m interested in patronizing. If I’m not, then why I am I being made to pay for it?

Let’s not even get into how constitutionally or morally suspect the earmarks process is.

Some people are fooled into thinking that someone else is paying for the goodies that our congressmen “bring home.” But any reasonably educated person (as opposed to overeducated, perhaps) knows that it’s a little like the person who stole your silverware coming back for a visit bearing a nice gift of a serving fork. Gee, thanks.

Posted by Marc Hodak on March 13, 2008 under Revealed preference |

This entry begins to answer a very relevant, but rarely asked question in the debate on immigration: how much is immigration worth to relatively unskilled immigrants? In other words, if you were relatively poor living outside of the U.S., how much would it be worth to become one of the poor inside the U.S.? The answer appears to be a small but significant risk to your life plus $4,000.

That, plus the mindless persecution of native Americans from England, France, Germany, etc. who don’t think we have any room for more. Plus the plans of idiot politicians who have no idea what they’re up against in trying to stem this tide, and are willing to betray the liberties of those who live here legally to try to stop those that don’t.

Now, if poor people are willing to pay thousands of dollars to get across our border illegally, how much can we increase the cost per person with all the measures that the most outrageous wall-builders are planning to implement? Will that increase their costs significantly? At all?