Posted by Marc Hodak on July 14, 2009 under Invisible trade-offs, Reporting on pay |

One of the more persistent fallacies about health care costs is that they make our businesses less competitive. The reasoning goes that our companies must bear health care costs directly, while their European counterparts don’t. If the government took over those health care costs by providing universal coverage, the costs to business would drop correspondingly and, presto, they become more competitive.

As any good economist knows, this reasoning is incomplete. To the extent that health care costs drop for companies, taxes to cover those health care costs now borne by the government will go up. Since those taxes will be paid by workers–mostly the same workers now getting coverage from their companies–the costs of health care will have simply shifted from the companies to the workers. But this would not represent the likely equilibrium.

Companies would have to compensate their workers the same regardless of whether health care coverage was part of the compensation package or not. (This may not be obvious on first blush, but it’s true–trust me.) And since workers are bearing a higher personal cost via their taxes, they would require higher compensation to cover those costs, which they could demand in a competitive market for talent (again, what companies don’t provide in one kind of benefit, they will need to replace with another or with cash). Of course, the people forced to exchange cash for company health care coverage aren’t exactly the same people getting their taxes raised in exchange for government health care coverage, which would create a new kind of equilibrium–this all gets sorted out by the market in its own, unpredictable way.

This view of total company costs being a wash regardless of whether companies or the government are providing the coverage is well accepted by economists of every stripe, from Bush’s former CEA Chairman Gregory Mankiw to Obama’s current CEA Chairwoman Christine Romer (who called this argument “schlocky”).

Yet, the Wall Street Journal publishes an entire article based on this fallacy.

At some businesses, in fact, health care is the highest expense after salaries—with devastating consequences. Owners must skimp on vital investments like marketing and research. Some can’t hire the people they want because top candidates demand premium coverage. Or they end up understaffed because of the high cost of insurance—and lose potential clients as a result.

Clearly this Wall Street Journal writer doesn’t read the Wall Street Journal.

Posted by Marc Hodak on July 7, 2009 under Collectivist instinct |

In a WSJ editorial, Gordon Brown and Nicholas Sarkozy go after people who make significant bets on the future of oil prices. I know that definition applies equally well to oil companies, airlines, bulk shippers, commodity traders, etc., but the dynamic duo are choosing to apply that label only to “speculators” (i.e., those evil traders/hedge funds).

And what is their complaint?

“For two years the price of oil has been dangerously volatile, seemingly defying the accepted rules of economics.”

and

“Those who rely on oil and have no substitutes readily available have been the victims of extreme price fluctuations beyond their control — and apparently beyond reason.”

If we get rid of the adjectives, redundancies, and weasel words, we get:

“For two years the price of oil has been dangerously volatile, seemingly defying the accepted rules of economics as often happens in uncertain economies.”

and

“Those who rely on oil and have no substitutes readily available have been the victims of experienced extreme price fluctuations beyond their control — and apparently beyond reason.”

The difference is that absent the adjectives, redundancies, and weasel words like “seemingly” and “apparently,” the clarion loses its force.

The combination of selective labeling of one group of traders as “speculators” based solely on the type of firm that employs them, and using language to blame natural occurences on conspiracies is typical of the cargo cults from which civilization evolved. Such misuse of language should not be acceptable in civilized societies, except that our comfort has far outstripped our collective ability to understand its true source.

Posted by Marc Hodak on July 5, 2009 under Movie reviews |

Pixar’s secret to their dominance over other movie studios: their films tell a good story. Other studios offer great acting, as does Pixar. Other films have great cinematography and graphics, often good enough to match Pixar’s spectacular animation. But Pixar’s movies have to appeal to the imagination of kids, and they do so by telling imaginative stories.

As with other Pixar films, Up begins with a novel back story (think retired superheroes, as in the Incredibles, or the desolation of Earth via hypercommercialism, as in Wall*E), before getting to the real story. Up begins with 10-year old Carl worshiping an adventurer named Charles Muntz who adorns the silver screen in the film’s alt-1930s. Little Carl then meets little Ellie, who quickly pulls him into her vivacious, adventurer’s fantasy life, and then into an adult life, highlighted by a shared dream of going to Paradise Falls, South America, as well as the more mundane dream of raising a family together. In 15 minutes, we see Carl and Ellie’s whole life which, alas, ends with neither children nor exotic travel.

The real story is how old man Carl decides to escape his retirement home destiny, and belatedly fulfill his promise to Ellie by flying their house to Paradise Falls using thousands of balloons. Carl is unexpectedly joined by the young, fabulously obese Wilderness Explorer, Russell. (There is nothing functional about Russell’s obesity in this story, which makes the device curious given Pixar’s target audience and PC morality.) At first blush, Russell echoes the youthful explorer spirit possessed by Carl about six decades years earlier, now rekindled. But Russell’s story turns out to a bit different.

Warning: Spoilers under the fold.

Read more of this article »

Posted by Marc Hodak on July 3, 2009 under Economics, Invisible trade-offs |

And does a great job of it. He leads with a great punch:

– “The American people overwhelmingly favor reform.”

If you ask whether people would be happier if somebody else paid their medical bills, they generally say yes. But surveys on consumers’ satisfaction with their quality of care show overwhelming support for the continuation of the present arrangement. The best proof of this is the belated recognition by the proponents of health-care reform that they need to promise people that they can keep what they have now.

My own summary: I’m amazed at the number of otherwise intelligent people who favor reform on the theory that we can’t individually afford the skyrocketing costs of health care, but that we can afford it collectively, and that by increasing the degree to which I’m paying for your health care and you’re paying for mine, we’ll bring those overall costs under control.

Posted by Marc Hodak on July 2, 2009 under Executive compensation |

Here is a sample of what it looks like they are considering:

– A written description of risks posed by their compensation policies

– Disclosure of potential conflicts in compensation consulting

– Disclosure of the market value of stock options at the time they are granted, instead of over the time period over which they are vested

I will be preparing my comments to SEC request 34-60218 over the next couple of weeks, but my preliminary comments:

– A discussion of the risks posed by compensation policies sounds good, but this is new territory for everyone who hasn’t thought systematically about this. I’m afraid that the people requesting this have no idea what to look for, and the directors charged with providing such disclosure will have no idea what to say.

– Disclosure of compensation consulting conflicts is also a good idea, but it should not be in the form of simply disclosing what is paid to the consultants, as the unions and their congressmen are asking. What does $$$ paid tell investors? Too low? Too high? Too biased? If this is really about conflicts rather than just how much I get paid to advise companies, you can get a much better idea by having companies disclose the fees earned by a given consultant for providing compensation advice as a percentage of overall fees for providing consulting services to the company. It could just be a range, too, like > 50%, >100%, >1000%, or Towers Watson.

– The only beneficiaries to the proposed rule change for the way options are disclosed would be the press and union activists that are primarily behind this proposal. The press would get a bigger number to report in the “total” columns. (This figure is already being reported in another table; but someone is apparently too lazy to toggle down a few pages it. Yeah it’s a big, hairy disclosure, but don’t blame me.) This bigger number would make even less sense than the big number they get to report now. If we’re not going to go with an economic measure of granted equity value in the total column (which the current disclosure rules don’t allow), we should just let the companies disclose enough for people who know how to use calculators to figure it out themselves, using whatever methodology they can sell to the only people to whom this really should matter–the investors.

Posted by Marc Hodak on July 1, 2009 under Collectivist instinct, Regulation without regulators |

In this case, though, I appear to be in good company:

The standard competitive market model just doesn’t work for health care: adverse selection and moral hazard are so central to the enterprise that nobody, nobody expects free-market principles to be enough.

Whenever I see such nonsense, I have to keep reminding myself that the trade theories for which Krugman won his Nobel Prize were explanatory and predictive. Krugman did not win a prize for mechanism design; he could not have predicted E-bay.

The idea of people bidding for stuff they can’t really see from people that they’ve never met is fraught with asymmetrical information. Honest sellers could not hope to compete with liars selling competitive products. Honest bidders could not hope to compete with fraudulent bids that may not be honored. Such a market, failing as it does the test of a “standard competitive market model” could never exist.

Except that it does.

Read more of this article »

Posted by Marc Hodak on June 29, 2009 under Scandal |

Nathan Hale, a hero of the American Revolution, condemned by the British to hang as a spy in 1776, famously said that he regretted that he had “but one life to give for my country.”

Madoff’s victims, many of whom have been condemned to a life of unexpected financial struggle, probably regret that the old devil had no more than one life to give for his crimes based on his 150 year sentence.

Is there a lesson from the Madoff debacle? I don’t know. His crime was a catastrophe for everyone who trusted him, and on a larger scale than anything before perpetrated by a private individual. Several ethical codes suggest a moral:

– Common sense: Don’t put all your eggs in one basket

– Western religion: If you do put all your eggs in one basket, make certain you know what that basket is made of

– Eastern religion: Better not to have many eggs; all baskets eventually fail

I don’t know if any of these are particularly helpful, but two morals–the ones most often cited in the press–are quite unhelpful:

– Fundamentalist: Greed is evil, and must be brought under control

– Political: The government needs more money and more power to prevent these things

The fundamentalist hypocrisy is that only certain other people are greedy. It appeals to the vanity that you or I would never succumb to the sin of wanting more than we have, much more if given the opportunity. In fact, greed was on both sides of the Madoff equation. The victims experienced a certain feeling every time they opened one of the fake statements telling them how much they “made.” That feeling was indistinguishable from greed, and it was indispensable to perpetuating the Madoff scheme. Nevertheless, I would never say that the victims deserved what happened to them.

Madoff’s real sin was, in fact, theft. Among the multitudes infected by the sin of greed, I believe that most of us are morally equipped to avoid perpetrating theft.

The government’s prescription, of course, is a joke. Madoff was registered with the SEC. They were furnished specific concerns about his legitimacy. The clean bill of health given by the regulators simply helped Madoff reel in more victims.

Posted by Marc Hodak on June 26, 2009 under Uncategorized |

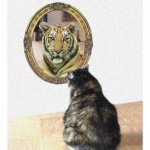

Hannah was a big, fluffy manx. She hated that. She hated that her appearance invited cuddling, as if she were some kind of plush doll. How demeaning.

“Don’t these humans understand? I’m a vicious beast. I have claws! And fangs! I could have them all for a snack, like that.”

Actually, Hannah didn’t have front claws, but she would sharpen them anyway against a door post or cardboard box when she saw me coming.

Hannah put up with us gamely. She would walk up to Tess and meow, and Tess would say, “Hi sweetie pie! Do you want hugs and kisses?” Hannah would furrow her furry brow as if to say, “How clueless are you, human? I’m shedding and I need brushing. Don’t pick me up…no…”

Hannah came in a package deal with Tess. For the first ten of her fifteen years, it was just the two girls. They were inseparable. Tess took Hannah on business trips; the kitty would greet her when she got back to her room. Tess thought Hannah was the most beautiful, intelligent, loving creature in the world. Hannah saw Tess as beautiful and loving, as well, but a little dense. Hannah would tell her what she wanted…food, brushing, scratching, etc… and Tess would ask, “What is it, sweetheart? Do you want hugs and kisses?” You could see Hannah’s reaction: “Oh, what a dear idiot.” She would then repeat her request more slowly, so her dopey mom could understand.

Of all the dim things her mom ever did, though, bringing me into their lives was the most inexplicable. “Don’t you understand, anything?” Hannah tried to warn her. “This big, ugly, stupid, hairless ape will ruin everything!” Hannah complained about me often. When Tess would return home, Hannah was always at the door to greet her, and tell her how I had tormented her with attention, or threats of attention, which for her was always unwanted, except for the chin scratching, and a little around the ear, when she indulged me.

Even worse, the Man that Tess latched onto had two boys, which besides all that unwanted attention meant a total of six big feet, lumbering around like a clueless field of swinging mallets. Since she normally operated in stealth mode to avoid petting, we did occasionally kick or step on her by accident. Her mom did the same thing, but Hannah assumed, as when any misfortune befell her, that is was somehow my fault.

Hannah met her end, as is common in old cats, with kidney failure. We treated her for months with hydration and medication which, from her vantage point was simply daily poking and having putrid liquids shoved down her throat. (Again, I was clearly to blame, even though her mom was often holding her.) On the second round of treatments for an infection, she finally said, “Enough.”

Hannah will be shipped to back to the farm in Missouri where she was born so her grandmother can bury her next to the family’s other favorite companions, Nick and Shorty.

I already miss the ornery little fluffball.

Posted by Marc Hodak on June 19, 2009 under Invisible trade-offs, Politics |

I picked up today’s Wall Street Journal this morning and saw a picture of two old Latvians literally at each others’ throats. The story behind that pic is that Latvia has promised pensions and public sector jobs to many, many people. Now that it can’t fund that promise (which was likely predictable at the time the promises were made), and is proposing to cut back 10 percent on pensions and 20 percent on public sector wages. My guess is that one of the people in the picture is a pensioner, and the other is a public sector employee, or spouse of one. My certainty is that they are frustrated by the perceived betrayal of their government, the reality that the losses are not going to hit everyone evenly, the reality that political influence will determine who gets what, and that they don’t have any. So they do what people often do in that situation–they turn on each other. Whenever the government must choose among the recipients of its largess, especially as it withdraws it, it is bound to create social strife.

You also see an echo of that in the headline story “Corporate Lenders Get Hit,” which describes how proposed rules for lending won’t hit all lenders evenly, and may even drive certain types of lenders out of the market. In this case, the disfavored lenders are figuratively hitting back via their lobbyists.

If one takes political debates on economic issues at face value, one can be forgiven for thinking that trade-offs are never necessary. Each side argues from an “all we need…” advocacy. When they admit of any conflicts their scheme may create, they invariably assert that sensible bureaucrats can make sensible trade-offs against fair standards, never admitting that fairness is impossible when the standards are arbitrary, and that nearly every standard creates, at its contentious, man-made boundary, winners and losers, often in the millions.

But when tough choices need to be made, as they always will be with the imposition of man-made rules, we are also apparently amused by pictures of people at each other’s throats, as long as it’s not us in those pictures.