Posted by Marc Hodak on July 27, 2009 under Executive compensation, Politics, Reporting on pay |

This paragraph says it all:

With public anger high over the rich pay packages awarded to some financial executives, Mr. Feinberg must walk a fine line between curbing pay at companies benefiting from taxpayer funds while not squeezing compensation so hard that it hurts the ability of companies to lure talent.

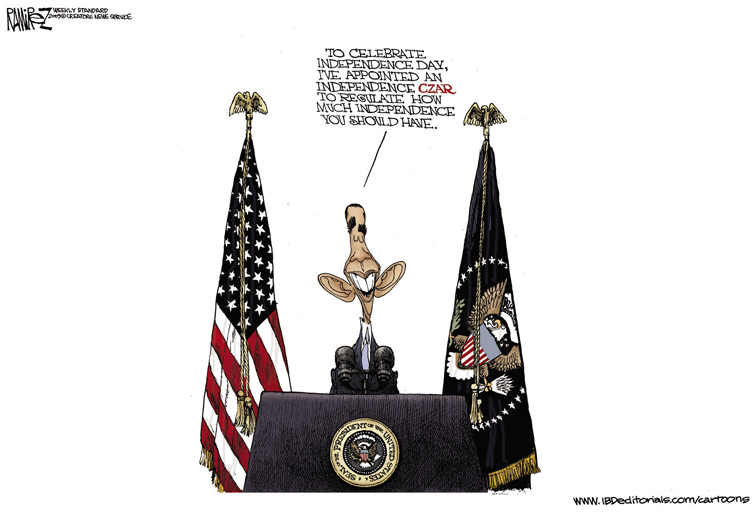

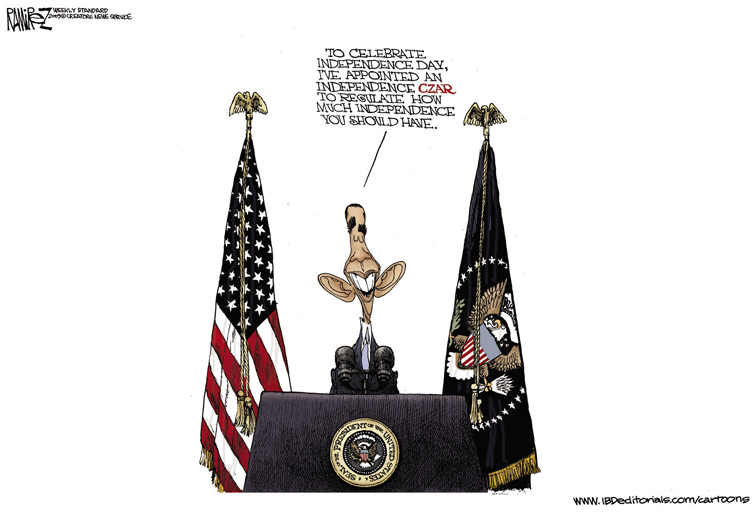

Mr. Feinberg is nicknamed the “Pay Czar,” no doubt because the Czar was such an inspiration in making the right trade-offs between populist demands and economic needs.

The irony is that Feinberg’s grandparents, like my own, may very well have been folks who escaped the Czar’s anti-semitic pogroms in the early part of the last century. We wouldn’t dream of nicknaming to Feinberg an “Oberfuhrer.” Perhaps a Commissar, Sotto Capo, or Underboss might be just as good. If not, why do so many people consider a ‘czar’ such a desirable thing in a free country?

Sounds good to me

Other Michael Ramirez cartoons

HT: Mike Perry

Posted by Marc Hodak on July 25, 2009 under Executive compensation, Politics, Reporting on pay |

It appears that Citi is on the hook for $100 million to the head of their Phibro division.

A top Citigroup Inc. trader is pressing the financial giant to honor a 2009 pay package that could total $100 million, setting the stage for a potential showdown between Citi and the government’s new pay czar.

The New York Times and Wall Street Journal, who would consider it well beneath them to publish front page stories about Jennifer Aniston’s romantic travails, have no qualms regaling the mob with stories about big dollars going to unpopular executives–the MSM’s version of porn for the business pages, which they peddle in the brown paper bag of “governance issues.” The government is easily embarrassed by these big dollar stories, which sets up “the showdown.”

So, am I suggesting that Andrew Hall, the guy in line for this bonus, is worth $100 million a year? No, I’m not. I’m sure he neither needs or deserves this princely sum. I’m simply suggesting that he should get what his contract says he should get.

A former official recently told me, “hey, contracts get challenged and renegotiated on Wall Street all the time, so why are you so upset when the government is doing it?”

I’m not upset when the government does it the way private firms typically would. A Wall Street firm renegotiates contracts quietly, to avoid the perception that they take their agreements lightly. No bank, however “powerful” they may be, could keep their doors open a fortnight if they could not be counted on to keep their word on a deal.

In contrast, the government uses these public spectacles to flaunt its disrespect for contracts, standing in a champion’s pose before the cameras, ignorant or uncaring that their knock-out is a blow to the rule of law.

Read more of this article »

Posted by Marc Hodak on July 22, 2009 under Collectivist instinct, Executive compensation, Politics, Scandal |

Missouri state's HR department

The nice people at MOSERS, the Missouri state pension fund, had a bonus plan. They beat their targets, earning their bonus. The Governor and legislature denied them their bonus.

Governor Jay Nixon called $300,000 in bonus payments to the 14-member staff of the Missouri State Employees’ Retirement System (MOSERS) “unconscionable.”

Unconscionable? What happened?

MOSERS’ incentives are based on a five-year cycle. The bonus payments paid this year were based on fund performance from January 1, 2004, through December 31, 2008. In that period, says [Executive Director Gary] Findlay, MOSERS had an overall return of 3.9% compared with its benchmark of 1.8%. (the benchmark is the performance of the asset allocation if it were invested passively).

The difference to MOSERS between a 3.9% rate of return and a 1.8% rate of return over that period, points out Findlay, is $600 million. So, the MOSERS investment staff added $600 million in value to the fund’s assets for bonus payments of $300,000, which is 5/100 of 1%.

So, tell me again, why did the politicians hose the MOSERS fund managers?

[Chairman of the legislature’s pension committee, Senator Gary] Nodler argues that payment of bonuses makes no sense in any year in which the fund experiences no actual growth. When the fund loses money, he says, then there is no money from which to pay the bonuses except to go into current assets. And that, he says, is a misappropriation of funds and a breach of fiduciary responsibility.

Makes no sense, indeed.

I give Nodler points for creativity, however. I have never heard a “breach of fiduciary responsibility” allegation used to cover up a breach of contract and a breach of good faith. You have to have a highly cultivated sense of mendacity to make this stuff up while summoning outrage for the cameras.

If the politicians had a shred of integrity, they would have told their pension fund managers five years ago that they would under no circumstances get any bonuses when absolute returns were negative. That way, the managers could have evaluated their compensation fairly versus their other opportunities, and decided whether they wished to stay or take their talents elsewhere. Given that the pols agreed to a bonus plan, their ignorance of its terms, or difficulty in explaining to the public why they are making payouts, is not a reason to stiff their employees. At best, if they decided after the fact that they wanted to pay for absolute performance rather than relative performance, then they should recalculate the bonuses earned in past years under this plan on an absolute basis, and pay them consistently. As it stands, the Missouri politicians were content to pay bonuses based on relative performance when peer fund returns were positive, but for absolute returns when the funds are negative.

And that is why politically run systems can’t outperform private sector ones.

Posted by Marc Hodak on under Invisible trade-offs, Politics |

Liberal blogger Ezra Klein is dubious about Obama’s pleas to progressives: that whatever happens in each house of Congress, he will fight in conference to uphold his “bottom lines,” which consist of affirmative answers to these questions:

Does this bill cover all Americans? Does it drive down costs both in the public sector and the private sector over the long-term. Does it improve quality? Does it emphasize prevention and wellness? Does it have a serious package of insurance reforms so people aren’t losing health care over a preexisting condition? Does it have a serious public option in place?

Never mind that he’s claiming with a straight face that a central planning system, which is what a “serious public option” will inevitably devolve into, is likely to produce a combination of widespread availability, decreasing costs, and improving quality–something that no government-run system has ever produced whether it be shoes or schools. And after all this, Professor Bainbridge feels Obama has left some things out:

- Nothing about Americans being able to keep the doctor they have now

- Nothing about Americans who are satisfied with their health care insurance being able to keep their existing policy

- Nothing in it about preserving opt-outs so that those who don’t want socialized medicine can keep private plans that fund procedures and drugs the government is unwilling to cover

- Nothing about how to pay for it without raising taxes to global highs

And then there is that thing that Obama, the progressives, and nearly every one else has left out in their “bottom line,” i.e., the prospect of finding cures for nasty things that don’t happen to have yet been cured. Innovation continues to be the ignored trade-off.

Posted by Marc Hodak on under Executive compensation, Invisible trade-offs |

The Sucker Proxy

While Congress presses ahead on “Say on Pay,” some institutional investors are beginning to rethink their position. The Say on Pay bill would require an up or down vote by investors each year for every public company. Even a small pension fund has investments in thousands of companies. How are they supposed to wade through the SEC-mandated morass that is executive compensation disclosure for every one of those companies sufficient to form an opinion on its adequacy and render a vote?

My firm plows through hundreds of proxies each year in order to determine the relative quality of compensation plans for our research purposes. We employ a team in India to get the data, and a couple of analysts in New York to plow through the data for a couple of months in order to reach opinions about specific firms. We’re down to doing this every other year because the effort is so costly, and the quality of plans don’t really change that much from year to year for any given firm.

Activist investors have sipped this tonic, and have come to a conclusion of their own:

Some shareholders say they have already gotten a taste of say on pay voting and find it unwieldy and time-consuming. The United Brotherhood of Carpenters, whose pension funds have about $40 billion in assets, says it cast more than 200 say-on-pay votes this year at companies participating in the government’s Troubled Asset Relief Program. These companies needed to get their pay plans ratified by shareholders…

“We think less is more,” said Edward Durkin, the union’s corporate affairs director. “Fewer votes and less often would allow us to put more resources toward intelligent analysis.”

Unfortunately, they’re making this case to congressmen who don’t even read the laws that they pass.

Posted by Marc Hodak on July 21, 2009 under Collectivist instinct, Reporting on pay |

This was an amazing transition. Here is the headline, sub, and lead:

Pay of Top Earners Erodes Social Security

Fund Expected to Be Exhausted in 2037

The nation’s wealth gap is widening amid an uproar about lofty pay packages in the financial world.

So, is this an article about Social Security? Wealth distribution? Or pay in the financial sector?

None of the above. It appears to be a critique of tax policy. I say “appears” because this article looks like a poorly edited complaint about how the affluent are not taxed enough in the opinion of the writer. Here is the paragraph among this swampy muddle that comes closest to saying what she is really trying to say.

Social Security Administration actuaries estimate removing the earnings ceiling could eliminate the trust fund’s deficit altogether for the next 75 years, or nearly eliminate it if credit toward benefits was provided for the additional taxable earnings.

Translation: If we take more money from the affluent, or reduce their benefits, we could eliminate the deficit in the social security trust fund.

No plausible actuarial basis is offered for these prescriptions, and no moral basis for why the government’s problem in managing SS becomes a justification for looting the income or wealth of the affluent. Just a gentle suggestion that breaking a deal can help the side that wasn’t screwed.

Of course, the ultimate sleight of hand, here, is that the extra dollars brought in by raising or eliminating the earnings cap on taxes will actually help SS solvency. Every dollar of those taxes will simply be spent on current projects, and future taxpayers will simply have a higher obligation to repay to the “Trust fund.” Bernie Madoff must shake his head in amazement thinking, “What a piker I was.”

Read more of this article »

Posted by Marc Hodak on July 20, 2009 under Stupid laws |

One of them is Jim Tedesco

No one can top a New York state legislator in achieving that delicate balance of self righteousness, populist money grubbing, and raw chutzpah:

Rich New Yorkers convicted of crimes would be forced — if [Republican Assemblyman Jim Tedisco’s] bill becomes law — to pay the state and federal governments for how much it costs to keep them in jail.

This is one of those ideas that sounded good when Jim was sitting on the toilet one morning, reading the paper about some illegally thrown bar mitzvah in a downtown prison. “Hmm. The rich have the money. Why do we taxpayers have to pay to house them in prison?” Naturally, he called his brainstorm the “Madoff bill” because everyone’s heard of Madoff who, as far as the law knows, doesn’t have a cent left.

A sliding scale would determine how much convicts would have to pay, based on their assets, under Tedisco’s bill. Those who are worth $200,000 or more would pay the entire tab, while those whose net worth is $40,000 or less would pay nothing.

Once he was done pushing that one out, certain things should have occurred to him:

– When someone is tried and convicted, legal penalties are pronounced at sentencing. You can’t extract extra penalties after sentencing.

– A person can only be sentenced for the crimes they committed. Since this proposed penalty would be based on the person’s assets not already attached under sentencing, which one would think would fully account for ill-gotten gains, then this idea amounts to a penalty for simply being “rich,” which last I checked wasn’t a punishable offense, even in New York.

Fortunately for the entertainment value of this proposal, Tedesco’s economic illiteracy is even greater than his legal illiteracy:

Convicts’ homes “or any equity found in it” would not be counted in determining their assets nor would their mortgage payments, tax bills or payments for child or spousal support, Tedisco said.

I love that “any equity found in it.” So you don’t have to bother looking under sofa cushions and in backs of closets to make sure you don’t miss any of that equity. And not counting mortgage payments, tax bills, or certain other payments as assets is a big help since they…uh, aren’t assets.

Of course, the thing I hate the most about this bill is the economics.

Read more of this article »

Posted by Marc Hodak on July 18, 2009 under Futurama, Invisible trade-offs |

to be able to see a great-great-great grandchild.

I don’t know that even the best health care system will get that for me, but I firmly believe that at the current pace of treatment innovation–which is by no means guaranteed–the first immortals are now among us, being pushed around in their strollers.

Posted by Marc Hodak on July 16, 2009 under Executive compensation, Reporting on pay |

Last year, Jamie Dimon and Lloyd Blankfein had a bad, bad year. They took it on the chin, and paid themselves no bonuses. Their JPM and GS colleagues collected little or nothing compared to earlier years, in some cases giving up millions that they might have legitimately earned based on their business units’ good performance in a tough year. In return, GS and JPM got…pilloried with their lesser rivals in the press as paragons of greed.

This year, it looks like GS and JPM are doing much better thank you. They will be increasing their pay accordingly. Members of Congress, once again, are in a tizzy.

“Recently reported bonus pools do suggest that there may be a return to the old ways which caused such damage to our economy. It reinforces our determination to adopt a reasonable set of legislative goals,” [Barney] Frank said.

This first sentence actually contains two false statements. First, the bonus pools don’t suggest anything, other than the fact that these two firms were quite profitable in the first half of 2009. Second, no evidence has ever been offered that JPM or GS did any damage to our economy. Of all the financial institution that were too big to fail, these two were farthest from failing and, in the case of JPM, saved a TBTF bank or two.

By the way, Members of Congress, including those on the finance committees directly overseeing Fanny and Freddie, suffered no diminution in pay in 2008. In fact, Barney Frank is taking in record amounts, including from the financial firms he is supposedly overseeing.

Read more of this article »

Posted by Marc Hodak on under Practical definitions |

Congress is fond of setting up oversight committees, and demanding that various agencies provide oversight to much of our economy. They are clearly contemplating definition 1 from Webster’s:

1 a: watchful and responsible care b: regulatory supervision <congressional oversight>

When one sees the actual, as opposed to the theoretical workings of our governments, state and local, it’s impossible not consider definition 2 as more appropriate:

2: an inadvertent omission or error

As the inestimable Henry Stern points out, oversight is one of the few words in the English language that also means its own opposite.