Posted by Marc Hodak on July 30, 2009 under Executive compensation, Reporting on pay |

Andrew Cuomo, Attorney General and Chief Compensation Scold of New York, raises his pitchfork once again with a report “No Rhyme or Reason,” condemning Wall Street’s “bonus culture.” The most damning piece of evidence?

Bonuses paid to executives at nine banks that received U.S. government bailout money in 2008 were greater than net income at some of the banks.

This is only surprising if you think of bonuses as something other than commissions based largely on net revenue, or perhaps net income from profitable divisions that likely saved their firms from bankruptcy.

The WSJ offers this puzzling assessment of the report:

The report is part of Cuomo’s investigation into the causes of the financial crisis. Not surprisingly, that investigation led to Cuomo’s office examining the compensation practices in the U.S. banking system.

Not surprisingly? The reason Cuomo’s investigation into compensation is not surprising is because he’s obsessed with Wall Street pay. A Cuomo investigation into the mating habits of pigeons would have led him to a critique of bank bonuses. In fact, Cuomo’s report does not even pretend to provide the slightest link between compensation practices and the financial crisis. I’m not saying there is no linkage to be made; this report simply provides none.

Read more of this article »

Posted by Marc Hodak on July 29, 2009 under Executive compensation, Practical definitions, Reporting on pay |

Congress is trying the belt and suspenders approach to keep the market from having another meltdown as we experienced last year. The belt is tighter controls at TBTF firms. The suspenders are the elimination of perverse incentives.

The thing is, if you want to eliminate perverse incentives, you have to know what they look like. According to an Equilar survey, here are some of the questions that companies are considering as they examine issues of excessive risk:

- Are we over using stock options?

- Do our incentive plans promote short-term thinking?

- Do we have the right mix between short and long-term goals?

- Do large maximum bonus opportunities promote risk taking?

- Are we using overly aggressive performance goals?

- Do our bonus plans focus on too narrow a set of goals?

- Do we have the right mix between fixed and variable compensation?

Six of these questions are sensible. One sticks out as completely bizarre to an incentive expert: “Do large maximum bonus opportunities promote risk taking?”

Of course they do. Is that supposed to be a bad thing? Entrepreneurs have unlimited bonus opportunities–thank goodness.

The question of a maximum bonus opportunity is simply the wrong question when talking about reward systems. The question they should be asking is whether steep bonus opportunities are combined with zero bonus opportunities. All the governance risk faced by a company is in the area where the participant would earn no bonuses unless they can get up into the green zone of bonus payouts with an all-or-nothing, double-down, longshot bet.

So, guess which of those questions most congressmen view as the most critical in determining “excessive compensation risk?” Yep, the risk that business executives might get paid too much.

Unfortunately, the reporting on the proposed regulation of compensation risk doesn’t even bother to define what “excessive risk” means at all, instead focusing on the political considerations of supporting or opposing any bill that purports to “contain” the excesses.

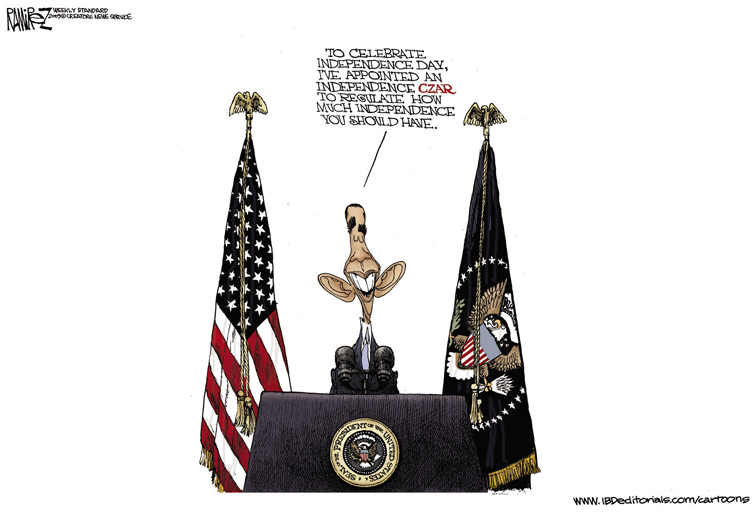

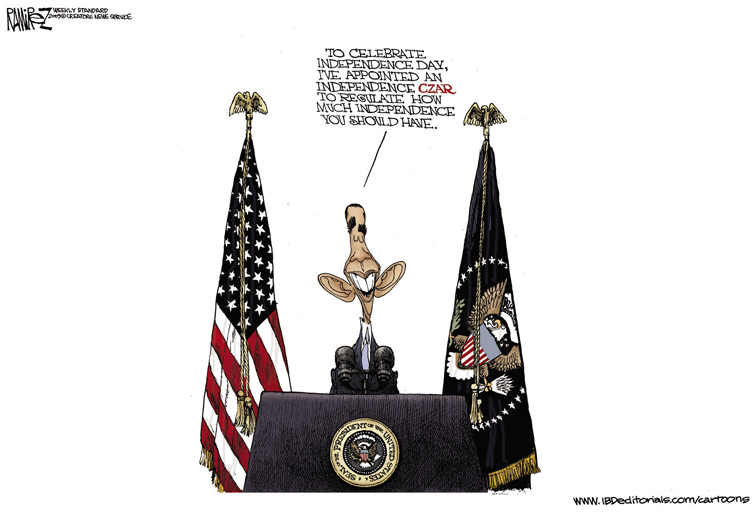

Posted by Marc Hodak on July 27, 2009 under Executive compensation, Politics, Reporting on pay |

This paragraph says it all:

With public anger high over the rich pay packages awarded to some financial executives, Mr. Feinberg must walk a fine line between curbing pay at companies benefiting from taxpayer funds while not squeezing compensation so hard that it hurts the ability of companies to lure talent.

Mr. Feinberg is nicknamed the “Pay Czar,” no doubt because the Czar was such an inspiration in making the right trade-offs between populist demands and economic needs.

The irony is that Feinberg’s grandparents, like my own, may very well have been folks who escaped the Czar’s anti-semitic pogroms in the early part of the last century. We wouldn’t dream of nicknaming to Feinberg an “Oberfuhrer.” Perhaps a Commissar, Sotto Capo, or Underboss might be just as good. If not, why do so many people consider a ‘czar’ such a desirable thing in a free country?

Sounds good to me

Other Michael Ramirez cartoons

HT: Mike Perry

Posted by Marc Hodak on July 25, 2009 under Executive compensation, Politics, Reporting on pay |

It appears that Citi is on the hook for $100 million to the head of their Phibro division.

A top Citigroup Inc. trader is pressing the financial giant to honor a 2009 pay package that could total $100 million, setting the stage for a potential showdown between Citi and the government’s new pay czar.

The New York Times and Wall Street Journal, who would consider it well beneath them to publish front page stories about Jennifer Aniston’s romantic travails, have no qualms regaling the mob with stories about big dollars going to unpopular executives–the MSM’s version of porn for the business pages, which they peddle in the brown paper bag of “governance issues.” The government is easily embarrassed by these big dollar stories, which sets up “the showdown.”

So, am I suggesting that Andrew Hall, the guy in line for this bonus, is worth $100 million a year? No, I’m not. I’m sure he neither needs or deserves this princely sum. I’m simply suggesting that he should get what his contract says he should get.

A former official recently told me, “hey, contracts get challenged and renegotiated on Wall Street all the time, so why are you so upset when the government is doing it?”

I’m not upset when the government does it the way private firms typically would. A Wall Street firm renegotiates contracts quietly, to avoid the perception that they take their agreements lightly. No bank, however “powerful” they may be, could keep their doors open a fortnight if they could not be counted on to keep their word on a deal.

In contrast, the government uses these public spectacles to flaunt its disrespect for contracts, standing in a champion’s pose before the cameras, ignorant or uncaring that their knock-out is a blow to the rule of law.

Read more of this article »

Posted by Marc Hodak on July 21, 2009 under Collectivist instinct, Reporting on pay |

This was an amazing transition. Here is the headline, sub, and lead:

Pay of Top Earners Erodes Social Security

Fund Expected to Be Exhausted in 2037

The nation’s wealth gap is widening amid an uproar about lofty pay packages in the financial world.

So, is this an article about Social Security? Wealth distribution? Or pay in the financial sector?

None of the above. It appears to be a critique of tax policy. I say “appears” because this article looks like a poorly edited complaint about how the affluent are not taxed enough in the opinion of the writer. Here is the paragraph among this swampy muddle that comes closest to saying what she is really trying to say.

Social Security Administration actuaries estimate removing the earnings ceiling could eliminate the trust fund’s deficit altogether for the next 75 years, or nearly eliminate it if credit toward benefits was provided for the additional taxable earnings.

Translation: If we take more money from the affluent, or reduce their benefits, we could eliminate the deficit in the social security trust fund.

No plausible actuarial basis is offered for these prescriptions, and no moral basis for why the government’s problem in managing SS becomes a justification for looting the income or wealth of the affluent. Just a gentle suggestion that breaking a deal can help the side that wasn’t screwed.

Of course, the ultimate sleight of hand, here, is that the extra dollars brought in by raising or eliminating the earnings cap on taxes will actually help SS solvency. Every dollar of those taxes will simply be spent on current projects, and future taxpayers will simply have a higher obligation to repay to the “Trust fund.” Bernie Madoff must shake his head in amazement thinking, “What a piker I was.”

Read more of this article »

Posted by Marc Hodak on July 16, 2009 under Executive compensation, Reporting on pay |

Last year, Jamie Dimon and Lloyd Blankfein had a bad, bad year. They took it on the chin, and paid themselves no bonuses. Their JPM and GS colleagues collected little or nothing compared to earlier years, in some cases giving up millions that they might have legitimately earned based on their business units’ good performance in a tough year. In return, GS and JPM got…pilloried with their lesser rivals in the press as paragons of greed.

This year, it looks like GS and JPM are doing much better thank you. They will be increasing their pay accordingly. Members of Congress, once again, are in a tizzy.

“Recently reported bonus pools do suggest that there may be a return to the old ways which caused such damage to our economy. It reinforces our determination to adopt a reasonable set of legislative goals,” [Barney] Frank said.

This first sentence actually contains two false statements. First, the bonus pools don’t suggest anything, other than the fact that these two firms were quite profitable in the first half of 2009. Second, no evidence has ever been offered that JPM or GS did any damage to our economy. Of all the financial institution that were too big to fail, these two were farthest from failing and, in the case of JPM, saved a TBTF bank or two.

By the way, Members of Congress, including those on the finance committees directly overseeing Fanny and Freddie, suffered no diminution in pay in 2008. In fact, Barney Frank is taking in record amounts, including from the financial firms he is supposedly overseeing.

Read more of this article »

Posted by Marc Hodak on July 14, 2009 under Invisible trade-offs, Reporting on pay |

One of the more persistent fallacies about health care costs is that they make our businesses less competitive. The reasoning goes that our companies must bear health care costs directly, while their European counterparts don’t. If the government took over those health care costs by providing universal coverage, the costs to business would drop correspondingly and, presto, they become more competitive.

As any good economist knows, this reasoning is incomplete. To the extent that health care costs drop for companies, taxes to cover those health care costs now borne by the government will go up. Since those taxes will be paid by workers–mostly the same workers now getting coverage from their companies–the costs of health care will have simply shifted from the companies to the workers. But this would not represent the likely equilibrium.

Companies would have to compensate their workers the same regardless of whether health care coverage was part of the compensation package or not. (This may not be obvious on first blush, but it’s true–trust me.) And since workers are bearing a higher personal cost via their taxes, they would require higher compensation to cover those costs, which they could demand in a competitive market for talent (again, what companies don’t provide in one kind of benefit, they will need to replace with another or with cash). Of course, the people forced to exchange cash for company health care coverage aren’t exactly the same people getting their taxes raised in exchange for government health care coverage, which would create a new kind of equilibrium–this all gets sorted out by the market in its own, unpredictable way.

This view of total company costs being a wash regardless of whether companies or the government are providing the coverage is well accepted by economists of every stripe, from Bush’s former CEA Chairman Gregory Mankiw to Obama’s current CEA Chairwoman Christine Romer (who called this argument “schlocky”).

Yet, the Wall Street Journal publishes an entire article based on this fallacy.

At some businesses, in fact, health care is the highest expense after salaries—with devastating consequences. Owners must skimp on vital investments like marketing and research. Some can’t hire the people they want because top candidates demand premium coverage. Or they end up understaffed because of the high cost of insurance—and lose potential clients as a result.

Clearly this Wall Street Journal writer doesn’t read the Wall Street Journal.

Posted by Marc Hodak on June 14, 2009 under Executive compensation, Reporting on pay |

Apparently, the answer is: just because the Corporate Library said so.

In a recent report called “What is the Impact of PE on Corporate Governance,” the corporate library concluded that their analysis:

…does not support the private equity claim to superior corporate governance as the companies enter the public markets. On the contrary, it indicates that buyout-fund-backed companies exhibit, in higher proportion than average, a number of features that have the potential to benefit executives at the expense of shareholders, including takeover defenses and boards whose independence may be compromised. In addition, the often-made assertion that private equity firms design compensation packages well suited to link pay to performance is not supported by this study. The companies lacked the key compensation structures that are widely believed to link pay to performance.

As someone who designs compensation packages for PE firms, and has often asserted that the designs were especially well suited to link pay for performance, I was interested in the basis for their conclusions. What key compensation structures were PE-backed firms lacking? Who are all those people who believed in them?

The report ended up offering a hopelessly muddled approach to compensation unsupported by any empirical analysis.

Read more of this article »

Posted by Marc Hodak on June 9, 2009 under Executive compensation, Invisible trade-offs, Reporting on pay |

So, you’ve played the populist card on executive compensation, Mr. President. You used it to provide cover for the mammoth, Democratic-payback-mondo-porkfest called the “Stimulus Package.” You used $500K to buy $787B. Well played, sir. But now that card is on the table. You can’t just pick it up again.

So, now we all have a bunch of silly-assed compensation rules that anyone could have predicted would create retention risk at American public banks. Sure, most people were saying, “Screw ’em. Where else could they go?” but we knew otherwise, didn’t we BO? We knew that any bank under TARP would chafe at the pay restrictions, in part because it put them at a competitive disadvantage. We knew that once you set some of the banks free, they would poach the others into submission, those big wounded banks still trapped under TARP, with all that taxpayer investment. Poof.

So here we are, on the eve of a TARP repayment by some banks that you have done everything to slow. But that part of the game is finally up. Now, what do you do?

Of course. You try to maintain some uniformity on the pay restrictions across all the banks, in and out of TARP. So, you’re forced to loosen up some of the restrictions on the remaining TARP banks while imposing new ones on the soon-to-be non-TARP banks. I know where you’re coming from, Mr. President.

Don’t worry, your secret appears safe, for now. The media has not a clue about your strategy or its motivation. Most of them are still at the “where else can they go?” stage. And the regular readers of this blog are plenty smart enough, but there’s only a few dozen of them–not enough to really alert the media. So, don’t worry. Do what you have to do. It’s all you can do, isn’t it Mr. President, as political choices lead to economic consequences that prompt more political choices…

Posted by Marc Hodak on May 27, 2009 under Executive compensation, Reporting on pay |

The new head of UBS is apparently faced with the same problems that were faced by the old head of UBS. One of the biggies is: how do you remain competitive (and solvent) as a bank without being competitive as an employer? Answer: you can’t. Another problem, then: how do you remain competitive as an employer without upsetting the public?

As in the U.S., the Swiss bank gave up its right to pay high bonuses when it got into trouble and accepted a bailout from their government, which basically capped the bonuses. The Swiss people, kindly and educated as they are, still suffer from the mob’s envy of the highly paid. UBS had a choice between being competitive or making the public happy, and they chose survival.

The “exceptional” salary increases “were necessary to safeguard our profitable business areas and to secure their success,” Gruebel said. “Following significant cuts in variable compensation, we had fallen well behind the market in certain areas, and that is unsustainable in the long run.”

Hmm. Companies being compelled to dramatically raise salaries when they were constrained from paying bonuses…who could have predicted that?

By the way, have you noticed that whenever Bloomberg (the same can be said for the WSJ) have multiple stories about a subject, they always start with the part about executive compensation?

Title reference here.