Posted by Marc Hodak on October 23, 2016 under Invisible trade-offs, Scandal, Stupid laws |

In the History of Scandal class that I taught in the mid-2000s, one of the lessons was that scandals have a life of their own, separate from the reality that they are nominally attached to, with the reality invariably being much less salacious than the stories that grew up around it. I have since seen the opposite phenomenon, as well–stories that could easily be made into huge scandals, but simply make the news one day to die the next.

In that context, I find myself asking, why isn’t New York’s attempt to outlaw Airbnb a scandal? The ban, and the now accompanying fines of thousands of dollars, is designed to restrict apartment owners from renting out their apartments to visitors. This has several obvious effects:

- Restricting the number of rooms available to visitors from out of town

- Making hotel rooms more expensive, so that the visitors that do come have less to spend on non-hotel items

- Preventing generally less affluent apartment owners from adding to their income (rich people don’t need to rent out their apartments to make ends meet)

But it should not be surprising that the bill was not called the “NYC Visitor Cap Bill,” or “Only Rich Visitors Allowed Bill,” or the “Ordinary Apartment Owners Don’t Really Need Extra Income Bill,” or the most honest title, “Government Supports Hotel Owners and Unions Bill.”

Read more of this article »

Posted by Marc Hodak on December 14, 2015 under Collectivist instinct, Invisible trade-offs, Politics |

New York Times staff

The long-awaited climate accord was signed in Paris. President Obama is taking a victory lap. The NYT breathlessly announced the implications for business:

It will spur banks and investment funds to shift their loan and stock portfolios from coal and oil to the growing industries of renewable energy like wind and solar. Utilities themselves will have to reduce their reliance on coal and more aggressively adopt renewable sources of energy. Energy and technology companies will be pushed to make breakthroughs to make better and cheaper batteries that can store energy for use when it is needed. And automakers will have to develop electric cars that win broader acceptance in the marketplace.

Perhaps. As long as investors, utilities, technology firms and auto makers can make money doing these things. Unfortunately, the climate deal does not prescribe any plan or policies to assure this, nor does it repeal the laws of economics, or the still-desperate need for global economic development. The obvious way to spur these results would be to implement a stiff tax on carbon, but that wasn’t a part of the deal, either.

With a carbon tax, all the other results listed above would follow. And if such a tax replaced income and sales taxes, it would achieve the key objectives of carbon reduction without stalling the economy, aside from dislocations in the energy sector. Politicians on the right wouldn’t propose such a replacement carbon tax because they don’t want to risk their support from oil companies, and many of them believe the problem of global warming is overstated. People on the left wouldn’t propose it because they are generally against replacing income taxes with something as “regressive” as a carbon tax. They would much prefer to add another layer of taxation, and use that money for their parochial purposes, including picking winners and losers in the technology development game, and to impose numerous new regulations on producers to restrict their emissions. Many of these people believe that central planning can get you as good results as market forces.

Unfortunately, the right has surrendered the discussion of climate change to the left, which means that to the extent that we get even ineffectual interventions, they are all but certain to hurt economic growth. People living in beachfront mansions may notice a two degree increase in global temperatures more than a two percent slowdown in economic growth. But people living in low-lying economies will be much more sensitive to an economic slowdown. Seventy five years ago, the Philippines and South Korea were at about the same place economically. The difference, with South Korea today having ten times the per capita GDP, was just two percent per year faster growth over that period. Which of these countries today is better able to weather warmer temperatures, rising waters, and more frequent storms?

The world may be warming with serious consequences ahead. Those who disagree with that prognosis are called “deniers.” What do we call those who deny the economic impact of their proposals? The last time we were told, “The experts are in complete agreement; give me a trillion dollars and control of one sixth of the economy,” things did not work the way their models predicted.

Posted by Marc Hodak on November 9, 2015 under Executive compensation, Invisible trade-offs, Pay for performance, Unintended consequences |

Safety first

This story starts with a dig:

Massey Energy was one of a handful of mining and energy companies that tied its chief executive officer’s bonus to safety performance in 2010. Today, former CEO Donald Blankenship goes to trial on charges stemming from a West Virginia mine explosion that killed 29 workers, the U.S. industry’s deadliest in almost four decades.

The story goes on to note that in the mining industry there is no correlation between having executive bonuses tied to safety metrics and the actual result of safer mines. In fact, many of the safest companies offer no safety bonuses for their top executives. Nevertheless, all of the people interviewed in the article claim that CEO incentives ought to be tied to safety much more than they are today.

Read more of this article »

Posted by Marc Hodak on October 18, 2015 under Executive compensation, Invisible trade-offs |

JLaw has ’em seeing red

Jennifer Lawrence recently penned an essay about no longer being willing to earn less than her male co-stars. Her feisty critique received an outpouring of feminist support inspired by her willingness to challenge the system. She has a point, of course, about female talent potentially being undervalued relative to male talent. This post is not about that. It is about the question I get most often regarding the extraordinarily highly paid: Does deciding to pursue more money than one avowedly needs make a person greedy?

The ‘greed’ question seems to have hardly come up with regards to Ms. Lawrence. Yet she earned $52 million last year. It is a fair guess that whatever millions she left on the table would not have the slightest impact on her lifestyle, which she readily admits. Her complaint isn’t about the money; it’s about the principle that women should get paid the same as men doing the same job. She wants parity with her peers.

So, maybe it matters why we want more money, e.g., to help others. Maybe that’s the difference between being greedy and not. Read more of this article »

Posted by Marc Hodak on September 8, 2015 under Economics, Executive compensation, Invisible trade-offs, Reporting on pay |

Against The Tide

High pay is controversial because there are inherently two, generally opposed, sides to the debate. This was well illustrated in a recent WSJ article about highly paid, star college football coaches. Given the topic, it’s appropriate to label the two sides “offense” and “defense.”

Offense

This is a good name for an instinctive reaction that we all have; we are offended by other people’s high pay. It’s a natural response. The moment any of us hears that someone has made millions of dollars, our knee-jerk reaction is “who can be worth millions?” We can’t help it. We also can’t help trying to supplement that emotional reaction with logical arguments. This is almost always done via comparisons to other people’s pay.

Last year, the current Alabama [Crimson Tide] coach, Nick Saban, made $7.2 million, roughly 11 times the salary of Alabama’s president.

Messrs. Saban and Meyer make 50 times that of an average full-time professor at their respective schools; Mr. Harbaugh makes 32 times more than an average full-time professor at Michigan…

Much is made of the fact that Alabama is a poor state with a median household income of $43,253, some $10,000 less than the national average. Public funding for higher education in the state was slashed by $556 million from 2008 to 2013, a 28% drop. Mr. Saban’s salary has risen 80% since he arrived at Alabama in 2007.

What makes these comparisons compelling is that they bring the discussion somewhat closer to the scale of our pay. If we get paid much less than top college coaches, for example—a better than 99 percent bet, even for readers of the Wall Street Journal—then we get to share the outrage that these people are making so much more than we are. I mean, who are these people? Are they really any better than us?

Some people call this reaction an instinct for fairness. Some call it envy. Regardless of the name, it is the first thing that strikes us when hearing “millions.”

Defense

And that is why any explanation or justification of other people’s millions can be viewed as a “defense.”

The easiest, and ultimately only way to defend high pay is to reference its negotiated nature. People don’t get what they deserve; they get what they negotiate. This negotiation is invisible to us, a distant, unwritten prequel, by the time we are reading about something like “$7.2 million.” When we say, “I can’t believe so-and-so is being paid that much,” we are really saying one of two things:

(1) “I can’t believe so-and-so was greedy enough to ask for or accept that much,” or

(2) “I can’t believe the person paying them that much really needed to.” Both criticisms represent a kind of an arrogance, if you think about it.

On the one hand, we are accusing the person who made a lot of a moral failing that any of us would likely succumb to if we were in their position. In my experience, the people who complain most loudly about other people’s pay are the least likely to turn down a windfall were it to come their way. On the other hand, we are accusing the person who paid the salary of being stupid, lazy, or corrupt with reference to their compensation decisions. We’re calling the owners, who are generally very successful themselves, financial dolts. On its face, this seems implausible. So, the sensible thing is to first ask the people paying millions what they were thinking.

Former Alabama President Robert Witt (now the chancellor of the Alabama university system), once told CBS’s “60 Minutes” that Mr. Saban was “the best financial investment this university has ever made…”

Mr. Saban had an immediate financial impact on Alabama. In 2007 the school was closing a $50 million capital campaign for its athletic department. After Mr. Saban arrived, the campaign exceeded its goal by $52 million. Alabama’s athletic-department revenue the year before Coach Saban showed up was $68 million. By 2013-14 it had risen to $153 million, a gain of 125%. (The athletic department kicked $9 million of that to the university.) Mr. Saban’s football program accounted for $95 million of that figure, and posted a profit of $53 million.

In other words, they were thinking that offering those millions in salary would pay them back in dividends. That bet doesn’t always work, but it was clearly working for Alabama. And these owners are considering all of the revenue streams likely to be impacted by their hire, the way any professional team owner would look beyond the gate receipts and TV licenses.

Mr. Witt said Mr. Saban also played a big role in the success of a $500 million capital campaign for the university (not merely the athletic department) that took place around the time the football coach was hired…

Ohio State has benefited in a similar way since luring Mr. Meyer, 51, out of a brief retirement in 2012. The university’s athletic-department revenue was up 14% to $69 million during the season last year, one in which Ohio State won the national title. In the aftermath of the title, the school’s merchandise sales totaled $17 million, some $3 million more than the previous year. More than half of that money goes to academics.

So, the defense of high pay is that if we give the recipient a portion of his or her value to the organization, the organization will benefit. That is true whether we are talking about coaches, or players, or real estate agents, or investment bankers. Economists call this paying for the individual’s marginal revenue product, and a principle of economics is that society as a whole is generally better off if every person is paid according to his or her marginal revenue product. Paying too much is a waste; paying too little risks ‘misallocation’ of that person’s talents.

The End Game

Whether we are talking about college football coaches, professional entertainers, or corporate executives, the debate often comes down to what game you’re playing. If you’re playing the game of fairness or envy, then you simply don’t want some people to make too much more than others, regardless of the economic consequences. If you’re playing to maximize overall social welfare, then you allow people to earn a significant portion of what they make for others, and let the chips fall where they may.

One might admit to a mix (or confusion) of motives in order pursue some middle ground. But in football, at least, no one scores in the middle ground.

Posted by Marc Hodak on August 3, 2015 under Invisible trade-offs, Unintended consequences |

What goes up…

Forking an extra $120 billion into the hands people paying college tuition might have had an effect in raising college tuitions. Who would have guessed? The irony is that the student loan and Pell grant programs were intended to make college more affordable for more people.

This new study doesn’t take into account the significant price discrimination practiced by colleges, which partly offsets the net cost per student, particularly for those from poorer backgrounds, versus the sticker price of tuition. Nevertheless, the average student that could once afford college by working summers now has to work a decade or longer to pay for school because of skyrocketing tuition.

So, according to the Fed study noted above, it seems that about half of tuition increase was the result of effective, if artificial, demand in the form of easy money for students. It’s certainly not because schools have gotten any better at educating their students.

Posted by Marc Hodak on June 15, 2015 under Executive compensation, Governance, Invisible trade-offs, Unintended consequences |

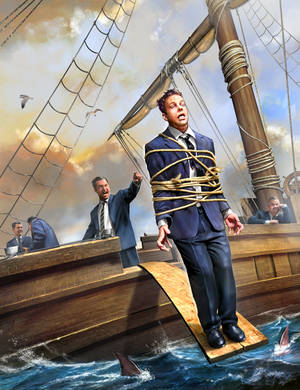

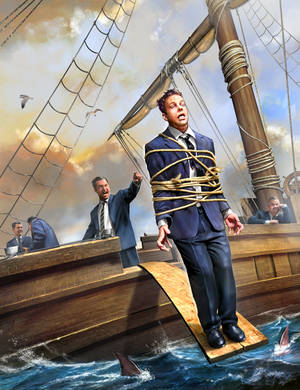

Hey you out there: Just kidding

Let’s say that you hire a captain for your ship, and for, say, tax reasons, decide that instead of running things from the bridge he should run things from the plank. You warn him that if anything goes wrong, he goes into the drink. But rough weather comes along, and you decide you still need him, so you don’t push him over the edge. At this point, you’ve hurt your credibility and pissed off the sharks.

That appears to be what is happening as activist investors increasingly get into the game of second-guessing corporate bonus plans. On the plus side, these shareholders are digging much deeper than the typical, diversified institutional investor possibly could. Marathon Partners, for instance, is criticizing Shutterfly’s plans that reward growth without assurance that it is value-added growth, which looks like a valid criticism.

But that doesn’t mean that activists investors necessarily know more than the boards they are criticizing:

Jana Partners LLC, which recently took a $2 billion stake in Qualcomm, has urged the company to tie executive pay to measures like return on invested capital, rather than its current yardsticks of revenue and operating income, according to a Jana investor letter. Such changes “would eliminate the incentive to grow at any cost.”

Yes, it would. But return on invested capital could instead create the opposite incentive, i.e., a bias against value-added investment. (If the investors really knew what was what, they would more likely require economic profit as the compensation metric.)

Although companies should generally be given the benefit of the doubt about their plans, they don’t do themselves any favors by trotting out the specter of retention risk when discussing variable compensation. Yet we often hear companies say, or using code words to the effect of, “Hey, we have to be careful that our incentive plans aren’t too tied to performance, because if they don’t pay out, we might lose key talent.”

Notice to Corporate Boards: Nobody buys this explanation.

And, by the way, if your variable compensation plan creates retention risk when it doesn’t pay out, then your compensation program is too weighted toward variable instead of fixed compensation. In other words, your salaries are too low and your target variable compensation is too high. In a well-designed plan, salary should cover the minimum amount of pay that would be needed to keep your executives around when your company is performing poorly.

Alas, too many corporate incentive plans are poorly designed, but not for the reasons usually toted up. These plans are a mess because the most important incentive of all is the incentive created by Section 162m of the tax code to underweight salary and overweight variable compensation. That puts public companies in a bind when incentive plans don’t pay off, which is clearly (and predictably) a recurring problem.

In other words, companies may be wrong-headed for conflating alignment issues with retention issues when arguing for slack in their bonus plans, but they come by this wrong-headedness honestly; it is a logical reaction to the unintended, deeply perverse encouragement our tax laws.

Fortunately, an increasing number of companies are starting to ignore the 162m salary limits. They are realizing that the harm that higher salaries may cause their shareholders in the form of higher taxes is easily outweighed by the benefits of more rational ratio of fixed vs. variable compensation for their management, one that militates against the real retention issues that too much compensation risk might cause.

Posted by Marc Hodak on March 23, 2015 under Governance, History, Invisible trade-offs |

Corporate Social Responsibility has become a hot topic. You can hardly talk about corporate governance these days without touching on it. In some areas, you might as well assume that CSR is in the background of every conversation about governance.

Being a history buff, I began to notice that a lot of “what corporations should be doing” sounded a little like reinventing the wheel. Corporations have, in fact, tried many things over the two centuries since they have risen to prominence. Not all of them have been run by greedy, rapacious bastards. Many of them, in fact, have been run by far-sighted, generous spirits intent on doing good while doing well. I thought that it might be worthwhile to review some of the boldest experiments in business history to see if we could learn any lessons from them.

Here are some early conclusions I have come up with.

Utopian Dreams

Posted by Marc Hodak on March 23, 2014 under Governance, Invisible trade-offs |

Transparency has its benefits. It enables shareholders to see into the company they own, and thereby judge whether it’s worth owning. The main mechanism for transparency in the corporate world is company disclosures. Does that mean that more disclosure is better? This article suggests otherwise:

In a coming paper in the Journal of Finance, Messrs. Loughran and McDonald suggest that size may be what really matters. They studied 66,707 10-Ks filed for the years 1994 through 2011. Controlling for factors including size and industry—bigger or highly regulated companies naturally file longer 10-Ks—they looked at how well the stock market appeared to read the performance of companies with lengthy filings.

Answer: Not so well. In the weeks after filing, shares of those with longer reports tended to be more volatile than those favoring brevity.

Somewhere along the line, disclosure became synonymous with transparency. Particularly in eyes of many governance mavens. Perhaps that’s because, since 1933 at least, the ability to compel disclosure has been the main tool in the federal regulatory tool chest. When you have a hammer…

I often introduce the Enron case with its 10-K from the year before the firm’s implosion. It’s difficult to go through that tome, including the volume of data on its infamous Special Purpose Entities, and claim that insufficient disclosure was the culprit. Their management accurately, if literally, conveyed the complexity of its operations.

This new study begins to explain how disclosure is not the same thing as transparency, and why the “more is better” instinct may be leading us astray.

Posted by Marc Hodak on November 11, 2013 under Executive compensation, Governance, Invisible trade-offs, Pay for performance |

Pay for performance seems like such a simple idea, and easy to accept as a basis for judging executive compensation. So why does it continue to create such discussion and controversy? Well, consider the following grid:

The key distinction is managerial performance versus company performance. An easy way to understand this distinction is to consider a gold mining company when the gold price has dropped significantly, but our company’s profits and stock price have dropped less than half of anyone else’s in our sector due to extraordinary management. It’s easy to see in such an example that our management has done great, but our shareholders have done poorly. Should such managers get a bonus?

When management and shareholder performance are strong, as in the upper right quadrant, the answer is obvious. When management and shareholder performance are weak, as in the lower left quadrant, the answer is obvious.

But what do we do when our gold company finds itself in the upper left quadrant? If we pay a bonus for this situation, we are open to the accusation of pay without performance by our investors. Our investors might bother to look at relative performance, in which case they might forgive bonus payments up to a point. But there is no way outside investors can gauge what the board can, i.e., that our managers actually did a great job given their situation, and that denying them a bonus may entail a significant risk of losing them to other firms that promise to compensate them for being great managers.

Paying a bonus for lower right quadrant performance is equally problematic. Most shareholders will let you get away with it because they are feeling flush. But those that don’t are on firmer ground in saying it would be pay without performance, that management was simply in the right place at the right time. In this situation, the downside to not paying a bonus is a little more subtle. If we deny managers a bonus for poor relative performance in the face of good absolute performance, then we MUST be willing to pay them bonuses for good relative performance even when the company suffers poor absolute performance. In other words, boards justifiably refusing to pay bonuses when they are in the lower right quadrant will eventually they find themselves in the upper left quadrant having to pay bonuses, or risk almost certain loss of their best managers. And we already highlighted the difficulty in adhering to a policy of consistently paying for relative, as opposed to absolute performance.

True to their pragmatic form, many boards resolve this dilemma by paying for both absolute and relative performance. This makes the plans more complicated, and does not completely eliminate at least some criticism of pay without performance, but it at least attempts a workable compromise. Fortunately, ISS (pdf) and Glass-Lewis provide a least some cover for pay for relative performance, but that only gets you so far.

What would you do?