Posted by Marc Hodak on June 15, 2015 under Executive compensation, Governance, Invisible trade-offs, Unintended consequences |

Hey you out there: Just kidding

Let’s say that you hire a captain for your ship, and for, say, tax reasons, decide that instead of running things from the bridge he should run things from the plank. You warn him that if anything goes wrong, he goes into the drink. But rough weather comes along, and you decide you still need him, so you don’t push him over the edge. At this point, you’ve hurt your credibility and pissed off the sharks.

That appears to be what is happening as activist investors increasingly get into the game of second-guessing corporate bonus plans. On the plus side, these shareholders are digging much deeper than the typical, diversified institutional investor possibly could. Marathon Partners, for instance, is criticizing Shutterfly’s plans that reward growth without assurance that it is value-added growth, which looks like a valid criticism.

But that doesn’t mean that activists investors necessarily know more than the boards they are criticizing:

Jana Partners LLC, which recently took a $2 billion stake in Qualcomm, has urged the company to tie executive pay to measures like return on invested capital, rather than its current yardsticks of revenue and operating income, according to a Jana investor letter. Such changes “would eliminate the incentive to grow at any cost.”

Yes, it would. But return on invested capital could instead create the opposite incentive, i.e., a bias against value-added investment. (If the investors really knew what was what, they would more likely require economic profit as the compensation metric.)

Although companies should generally be given the benefit of the doubt about their plans, they don’t do themselves any favors by trotting out the specter of retention risk when discussing variable compensation. Yet we often hear companies say, or using code words to the effect of, “Hey, we have to be careful that our incentive plans aren’t too tied to performance, because if they don’t pay out, we might lose key talent.”

Notice to Corporate Boards: Nobody buys this explanation.

And, by the way, if your variable compensation plan creates retention risk when it doesn’t pay out, then your compensation program is too weighted toward variable instead of fixed compensation. In other words, your salaries are too low and your target variable compensation is too high. In a well-designed plan, salary should cover the minimum amount of pay that would be needed to keep your executives around when your company is performing poorly.

Alas, too many corporate incentive plans are poorly designed, but not for the reasons usually toted up. These plans are a mess because the most important incentive of all is the incentive created by Section 162m of the tax code to underweight salary and overweight variable compensation. That puts public companies in a bind when incentive plans don’t pay off, which is clearly (and predictably) a recurring problem.

In other words, companies may be wrong-headed for conflating alignment issues with retention issues when arguing for slack in their bonus plans, but they come by this wrong-headedness honestly; it is a logical reaction to the unintended, deeply perverse encouragement our tax laws.

Fortunately, an increasing number of companies are starting to ignore the 162m salary limits. They are realizing that the harm that higher salaries may cause their shareholders in the form of higher taxes is easily outweighed by the benefits of more rational ratio of fixed vs. variable compensation for their management, one that militates against the real retention issues that too much compensation risk might cause.

Posted by Marc Hodak on June 2, 2015 under Executive compensation, Governance, Revealed preference |

The unanticipated death of a public company top executive can often create an observable market reaction. Sometimes, this reaction is not flattering, as when the stock price jumps five to seven percent when a CEO dies because there was no other way for the shareholders to get rid of him.

On the other hand, you get examples of what happened when the market was hit with news that Ed Gilligan, American Express President and heir apparent to the CEO, passed away suddenly on Friday. Amex stock dropped about ten cents per share (after accounting for changes in the market overall)—a drop of about $100 million dollars. Which answers the question posed in this title: Yes, some people are clearly worth to their shareholders what they are being paid.

Ironically, this financial hit was the result of good governance. Amex did what it was supposed to do in clearly identifying a likely successor in case they should suddenly lose their CEO, as well as pave the way for his retirement. The value of clarity about successorship is supported by empirical evidence. So, in a sense, what Amex has lost in a worthy successor, besides whatever else Gilligan uniquely provided to the company, was simply giving back what they had previously gained from doing the right thing in establishing a clear heir to CEO Kenneth Chenault.

And now Chenault, who just lost a close colleague for whom he clearly had great affection, must once again groom another successor.

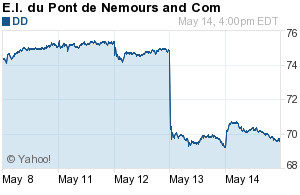

Posted by Marc Hodak on May 14, 2015 under Governance, Revealed preference |

Whoa.

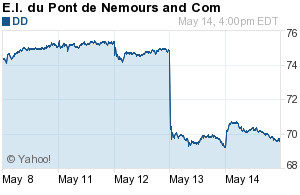

Those who have followed the Dupont/Trian contest know that the shareholders voted (barely) to retain the incumbent board. But two other, fascinating pieces of information are apparent from the aftermath of that vote regarding the investors’ reaction:

1. The market was surprised

2. The market was disappointed

A seven percent drop in the stock price is huge. Shareholders were clearly invested, so to speak, in seeing Trian win, even as they voted them down. So, while shareholders-as-voters accepted CEO Ellen Kullman’s explanation that Nelson Peltz does not know as well as she what is best for their company, shareholders-as-traders said, “Whoa, that was a terrible decision!” We assume that, being the same people, each making their judgments based on their individual, independent estimation about the future prospects of the company, and with the “wisdom of crowds” sorting out their discordant judgments into a useful, single verdict, we should see less schizoid outcomes.

Alas, this “crowd” effect works via very different mechanisms in proxy voting versus in market pricing. So, which result should management heed? Read more of this article »

Posted by Marc Hodak on May 3, 2015 under Executive compensation, Governance, Pay for performance |

The SEC has released proposed rules for disclosing pay for performance, based on the Dodd-Frank law requiring that each company provide “information that shows the relationship between executive compensation actually paid and the financial performance of the issuer, taking into account any change in the value of the shares of stock and dividends of the issuer and any distributions.”

As my regular readers know, “pay for performance” can be usefully evaluated only when we have appropriate definitions of “pay” and “performance.” Appropriate definitions depend on one’s purpose for making the evaluation. Pay-for-performance can be either an exercise in costing, i.e., seeing if shareholders are getting what they are paying for, or for determining alignment, i.e., seeing if management rewards are consistent with shareholder value creation. These can be different analyses, with the same underlying figures yielding very different conclusions.

Read more of this article »

Posted by Marc Hodak on April 6, 2015 under Governance, History |

Regulators are saying that they may want some of that fiduciary attention that boards currently, presumably owe exclusively to their shareholders. Last year, Fed Governor Daniel Tarullo broached the idea that bank boards should perhaps account for regulatory as well as shareholder interests in their governance to address the divergence between firm-level and “macro-prudential” needs. Tarullo suggested that this division of loyalty might supplement, if not somewhat obviate the need for, the other two approaches that the government has tried, i.e., increasingly constrained incentive plan structures and increasingly detailed banking regulations.

The incentive problem has been well covered here and here, as has the downsides of proposed regulatory remedies. Dodd-Frank includes a plethora of direct regulatory constraints to moderate the risk appetite of banks, among other things. Of course, that grand legislation failed to address TBTF or the GSEs with which the big banks competed, and—surprise!—a general feeling persists that regulation may not be enough.

One the one hand, we should have expected that conclusion long before Dodd-Frank was even passed. Contrary to the prevailing narrative, banks were working under a heap of government regulations in the run-up to 2008. Those regulations may have been the wrong ones, or they may have been poorly administered, but they undoubtedly contributed to market distortions that made ‘up’ look like ‘down’ in many derivatives transactions.

Rationalizing the regulations, and accounting for the complexity that they create (and their secondary effects), would have been a good start to improving bank governance. Instead we have greater regulatory complexity than ever, which means we have more potential distortions and perverse incentives built into our financial system than ever before. Given this reality, perhaps it makes sense to throw in the towel on trying to contain the externalities of our banking system via sensible regulation, and just tell the board of directors that they must begin to internalize those potential costs by accounting for regulatory interests alongside (or perhaps ahead of) shareholder interests.

Unfortunately, that approach has yet to work well in any other industry in which it has been tried. Instead, history suggests that regulatory cures beget regulation-induced problems, which beget more regulation, etc., until the whole sector becomes in essence, if not in fact, nationalized. This state of affairs continues, often for decades, until the manifest defects of this nationalization become obvious to everyone, and the sector gets substantially deregulated. And everything is better.

Until problems crop up again, and politicians feel compelled to do “something…anything.”

Posted by Marc Hodak on March 23, 2015 under Governance, History, Invisible trade-offs |

Corporate Social Responsibility has become a hot topic. You can hardly talk about corporate governance these days without touching on it. In some areas, you might as well assume that CSR is in the background of every conversation about governance.

Being a history buff, I began to notice that a lot of “what corporations should be doing” sounded a little like reinventing the wheel. Corporations have, in fact, tried many things over the two centuries since they have risen to prominence. Not all of them have been run by greedy, rapacious bastards. Many of them, in fact, have been run by far-sighted, generous spirits intent on doing good while doing well. I thought that it might be worthwhile to review some of the boldest experiments in business history to see if we could learn any lessons from them.

Here are some early conclusions I have come up with.

Utopian Dreams

Posted by Marc Hodak on October 2, 2014 under Executive compensation, Governance |

Yesterday, Coca Cola caved in to the bad press regarding the equity plan they proposed last April–and passed by nearly 90 percent of voted shares–by altering their equity award guidelines. It’s fun to speculate about the various forces arrayed for or against the Coke equity plan, and what Warren Buffet thinks, and how the press has reported the issues at stake. But I’ll sidestep all the juicy speculation and bright fireworks and go straight to the only thing that matters, or ought to matter, to shareholders: Is the new Coke policy better than the old Coke policy?

Let’s start with the policy change itself, which has three parts:

1. Coke will be providing more transparency about the rate at which equity is being awarded (burn rate, dilution, and overhang)

2. Coke will be using equity more sparingly in “long-term plan” awards, instead favoring cash

3. Coke will be awarding far fewer options from their equity pool than before relative to performance-based stock

The effect of the latter two policies will be to significantly reduce the number of shares used to compensate management. What they are NOT changing is just as important as what they are changing.

– They are not changing the target value of “long-term plan” awards to management. If an executive had a $1 million target long-term award, they will continue to have a $1 million long-term award; it will simply be paid more in cash than in equity.

– They are not changing eligibility for awards. They continue to believe that equity awards should be broad-based within the company.

So, what have the shareholders gotten out of these changes? Well, management and the board will finally be able to step out of an unwanted limelight over pay. Shareholders benefit from managers and directors being able to focus on business with one less distraction. As for the economic benefits to the shareholders, that’s pretty easy to estimate, too: Nothing. Read more of this article »

Posted by Marc Hodak on September 5, 2014 under Futurama, Governance |

Fox, in the kind of an understatement we have come to expect in the marketing of reality TV, is billing its new fall series “Utopia” as “television’s biggest, boldest social experiment.” The show’s premise taps into the age-old dream of creating a perfect society. This dream burns particularly brightly in the treasured eighteen to thirty-four year-old demographic, marinated in the you-can-do-anything ethos. These are the very folks who would ask: Can a group of random strangers actually create a perfect society?

No, they can’t.

It sounds almost mean to put it so bluntly, as if I wanted them to fail. Not true. Read more of this article »

Posted by Marc Hodak on August 5, 2014 under Executive compensation, Governance |

Just published in Directors & Boards. The summary:

Nucor’s classic incentive plan contained three elements:

1) A fixed share of profit growth…

2) …without limit

3) Annual grant of standard stock options

The company was enormously successful because of this plan. It looks like everything that shareholders care about is imbedded in this plan. Empirical evidence strongly supports these plan elements as being good for shareholders.

Yet none of them would pass muster with ISS today.

So, if you’re a director of a public company, and you know what reason and evidence suggest, and you had a choice between adopting a Nucor-style plan or hewing to ISS’s standards, what would you do?

Unfortunately, we know what they are doing, and that it is hurting the value of public companies.

Posted by Marc Hodak on May 30, 2014 under Executive compensation, Governance |

On Monday, Staples, Inc will try to win its “Say-on-Pay” vote with ISS recommending against approval the executive compensation plan. ISS made its recommendation based on its usual arbitrary, micro-managing concerns which are not the subject of this post. Here, I want to highlight the problem Staples created for itself, without anyone’s help, and unintentionally revealed in this pair of sentences:

The [Compensation] Committee … recognized the need to address retention of key talent and to continue to motivate associates in light of the fact that we did not pay any bonus under the Executive Officer Incentive Plan or Key Management Bonus Plan in 2013 and 2012.

As a result of the changes to the compensation program in 2013, an average of 84% of total target compensation (excluding the Reinvention Cash Award) for the NEOs was “at risk” based on performance results, and 100% of long term incentive compensation was contingent on results.

Anyone reading Staple’s proxy could be forgiven for thinking that these two sentences have nothing to do with each other, notwithstanding that they appear consecutively in this proxy. It’s clear that neither the authors of this disclosure nor the board that approved it saw the connection, either. But look carefully at what they are saying.

Read more of this article »