Posted by Marc Hodak on February 25, 2014 under Executive compensation, Stupid laws |

Paradox: a statement that is seemingly contradictory or opposed to common sense and yet is perhaps true

The media in Europe are starting to call skyrocketing banker salaries across Europe the “bonus paradox.”

The EU limit on bonuses to 100 percent of salary (or 200% with shareholder approval) is ushering a paradoxical parade of unintended consequences. But just because consequences are unintended doesn’t mean they are unpredictable.

The economic ignoranti fully expected overall banker pay to be clipped by the EU measure. José Manuel Barroso, president of the European Commission said, “This is a question of fairness.” So, there it is.

Except that banks are not going to lose their most mobile workers for insufficient pay. Bankers, you may not be surprised, are good with money; they know what they are worth, and they are confident about it. They would actually prefer to be paid for performance, and are unhappy about the higher mix of fixed-to-variable compensation that effectively caps their upside, even if it leaves them more-or-less whole in expected value terms. But they will not accept less than what the guy down the street, or in New York or Hong Kong, will pay them.

The more sophisticated proponents of this law would say that it wasn’t the level of pay they were actually after, but the structure of pay in the form of bonuses that encouraged undue risk taking. They’re OK with the new compensation mix, and feel it will reduce financial risk. They are wrong, too. Yes, it is theoretically possible that perverse incentives can lead to undue risk-taking, and there was certainly some of that going on in the lead-up to the financial crisis. But there is zero evidence that bonus structures that have been around for decades, and whose incentive effect have been understood and refined and overseen for decades, would all of a sudden in the middle of the aughts suddenly be the cause of a global catastrophe. If you want to properly diagnose a cause, look at what has changed, not at what was always there. If that logic doesn’t persuade, then perhaps empirical evidence would, and the evidence denies the hypothesis. If logic and empiricism don’t sway you…then you are fully qualified to run for the legislature.

Unfortunately we are not done with paradoxes and unintended consequences. Read more of this article »

Posted by Marc Hodak on January 26, 2014 under Executive compensation |

About a year ago, I wrote about the new restrictions the EU imposed on banker bonuses, i.e., limited to two times their salaries. I predicted that bankers, being better versed than legislators on how money works, would likely nominally raise salaries, then claw back a portion of that nominal salary based on performance. One year later, it appears that is pretty much what Goldman Sachs and Barclays (at least) are doing:

Starting this year, certain Goldman employees will earn a salary, a bonus and some “role-based pay.” It may be paid monthly or divided, with some paid monthly and some accruing to be handed out at the end of the year. The new type of pay will not be used when tallying pension contributions. The bank may be able to claw some of it back, and it can change from year to year. But it will have the effect of driving up base salaries.

Yes, to some extent base salaries are going up, but the deferred portion subject to claw-back serves exactly the same function as a target bonus that is realized (or not) based on performance. And this bumped up “salary” provides enough headroom to provide double the amount again for bonuses.

For an example, here is how the numbers worked for Goldman. Last year, average salary for Goldman employees covered by the new law was about $750,000, and their average total pay was about $4.5 million. This year, Goldman bumped up these folks salaries by about $1.5 million, for a total “salary” of $2.25 million. Half of that “salary” increase (hence the quotes), i.e., $750,000, is subject to a performance-based clawback. If, instead, the employee performed well, they would get their total “salary” of $2.25 million. If they performed very well, they could get another $2.25 million, for a total pay of about $4.5 million. In other words, they could end up exactly where they were before, but via a more complicated path to be in compliance with the letter of the law.

If you can’t follow these numbers, that’s OK, you could still become a legislator. If one were serious about containing bankers’ pay, they would be pursuing a very different, more finance-literate path of regulation. I’m not holding my breath.

* That’s a longer headline than “Dog bites man,” but I must be cognizant of what search engines will pick up.

Posted by Marc Hodak on November 11, 2013 under Executive compensation, Governance, Invisible trade-offs, Pay for performance |

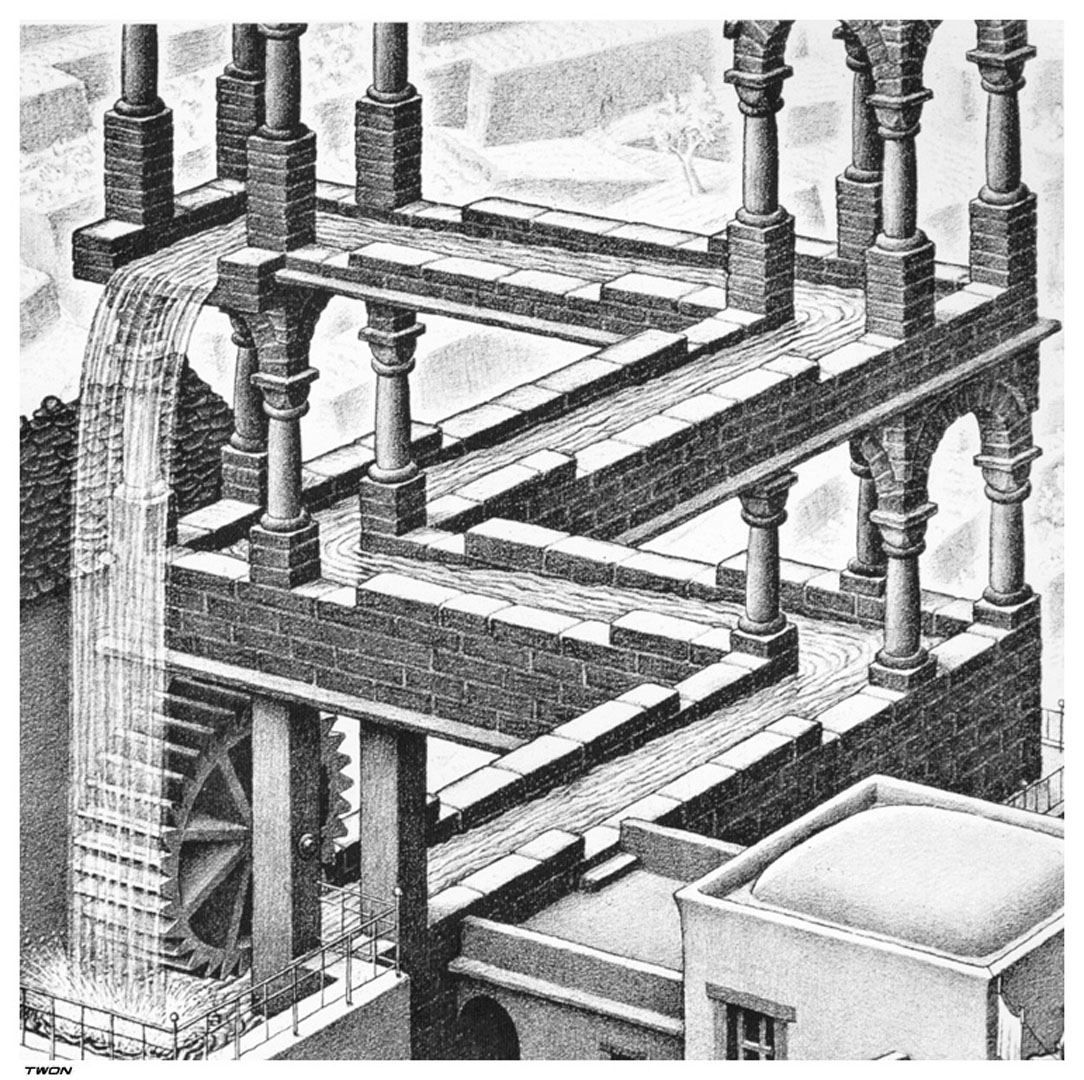

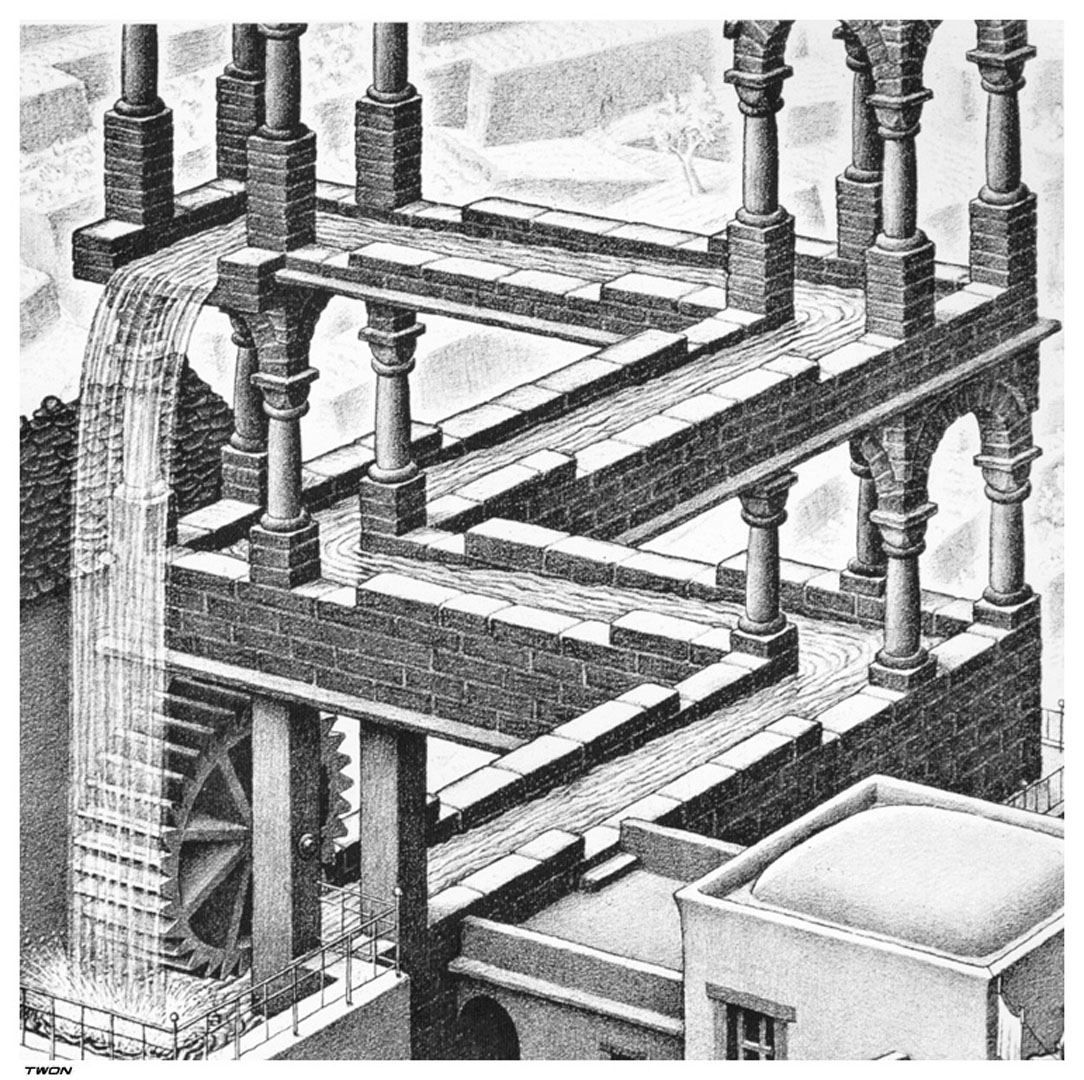

Pay for performance seems like such a simple idea, and easy to accept as a basis for judging executive compensation. So why does it continue to create such discussion and controversy? Well, consider the following grid:

The key distinction is managerial performance versus company performance. An easy way to understand this distinction is to consider a gold mining company when the gold price has dropped significantly, but our company’s profits and stock price have dropped less than half of anyone else’s in our sector due to extraordinary management. It’s easy to see in such an example that our management has done great, but our shareholders have done poorly. Should such managers get a bonus?

When management and shareholder performance are strong, as in the upper right quadrant, the answer is obvious. When management and shareholder performance are weak, as in the lower left quadrant, the answer is obvious.

But what do we do when our gold company finds itself in the upper left quadrant? If we pay a bonus for this situation, we are open to the accusation of pay without performance by our investors. Our investors might bother to look at relative performance, in which case they might forgive bonus payments up to a point. But there is no way outside investors can gauge what the board can, i.e., that our managers actually did a great job given their situation, and that denying them a bonus may entail a significant risk of losing them to other firms that promise to compensate them for being great managers.

Paying a bonus for lower right quadrant performance is equally problematic. Most shareholders will let you get away with it because they are feeling flush. But those that don’t are on firmer ground in saying it would be pay without performance, that management was simply in the right place at the right time. In this situation, the downside to not paying a bonus is a little more subtle. If we deny managers a bonus for poor relative performance in the face of good absolute performance, then we MUST be willing to pay them bonuses for good relative performance even when the company suffers poor absolute performance. In other words, boards justifiably refusing to pay bonuses when they are in the lower right quadrant will eventually they find themselves in the upper left quadrant having to pay bonuses, or risk almost certain loss of their best managers. And we already highlighted the difficulty in adhering to a policy of consistently paying for relative, as opposed to absolute performance.

True to their pragmatic form, many boards resolve this dilemma by paying for both absolute and relative performance. This makes the plans more complicated, and does not completely eliminate at least some criticism of pay without performance, but it at least attempts a workable compromise. Fortunately, ISS (pdf) and Glass-Lewis provide a least some cover for pay for relative performance, but that only gets you so far.

What would you do?

Posted by Marc Hodak on October 30, 2013 under Executive compensation, Governance, History, Unintended consequences |

The last time that CEOs were routinely kept awake at night was during the merger wave of the mid-1960s.

The frothy ’50s turned out to be high tide for American industrial dominance, a time when we were rebuilding the world after a devastating war. CEOs had it pretty cozy then. As the tide began to recede, investors began to notice the accumulated waste made possible by a decade of easy growth. A few of them saw advantage in taking over the worst governed companies in order to restructure them. At that time, they could do so without warning, which is what made this environment so frightening to CEOs. Imagine never knowing when you might get a phone call telling you that you are out. This is like going trick-or-treating and fearing the “tricks” all year long.

Corporate executives of that period had grown up in a world where being a leader meant getting along with everybody, and knowing how to use the corporate treasury to buy allegiances, including labor, business partners, and politicians. These new people on the scene—called “raiders”—were after the whole treasury, in part to prevent it from being used as the CEO’s relationship kitty. The governance mechanisms of the day gave them access to it by simply taking advantage of the stock being cheap after years of neglect.

Worried incumbent CEOs reacted by contacting their congressmen, who also knew a thing or two about incumbency. This unholy partnership took control of the narrative. Instead of investors identifying bloated companies in order to restructure them and return excess funds to remaining shareholders, the incumbents claimed that:

“In recent years we have seen proud old companies reduced to corporate shells after white-collar pirates have seized control with funds from sources which are unknown in many cases, then sold or traded away the best assets, later to split up most of the loot among themselves.” (Sen. Harrison Williams, 1965)

The media bought it. The legend of the “corporate raider” was born. The off-hand mention of “unknown” funding sources added a hint of nefariousness. (Who did they think provided the funds? Why did it matter?) The media didn’t consider that any mechanism that made the sum of the parts worth so much more than the whole might actually be socially useful. Instead, they played on the conservative discomfort of seeing old line, industrial firms disappearing at the hands of destabilizing (and generally non-WASP) upstarts, and the liberal discomfort of “money men” involved in unregulated financial activities.

Thus, in the fall of 1968, Congress passed the Williams Act. This law prevented investors from making a tender offer for shares without giving incumbent boards and management a chance to “present their case” for continued control of the company—as if they hadn’t already had years to make their case.

Now comes the weird part. Read more of this article »

Posted by Marc Hodak on September 22, 2013 under Executive compensation, Politics, Stupid laws, Unintended consequences |

The SEC has finally proposed a rule on the infamous “CEO Pay ratio,” i.e., the ratio of CEO pay to that of the median worker. There has been plenty of debate about the pros and cons of this requirement. The primary criticism is that this ratio will not pass any cost/benefit analysis. Every company knows this is true. Most institutional investors know it, too, and don’t really care for this rule. In fact, the only people likely to benefit from this rule are the unions that pushed for it. Even their benefit is speculative since the unintended consequences of this rule are difficult to fully predict. For instance, it might encourage further outsourcing of relatively low-wage work to foreign companies, depressing employment. In other words, we could very well see the average pay of the median worker go up, but only if you don’t count the zero wages being earned by those who are laid off as a result of this law.

Given how dubious are the benefits of this rule, let’s turn to the costs. I have seen estimates of calculating this ratio for a large, multinational firm as high as $7.6 million. Being in the advisory business, that seems pretty excessive to me. By comparison, the average cost of complying with the dreaded SOX Section 404 was about $2 to $3 million for the typical company (which was about 10 times higher than the SEC estimated it would cost when they published its rules).

So, let’s say it costs about $2 to $3 million for a large company, which is a reasonable estimate for a multinational given the way the rules look right now. Well, about 10 percent of Fortune 500 CEOs made less than that in 2012. That’s right, we are almost certain to see quite a few companies paying more than they actually pay their CEO to figure out how much more their CEO makes than their median worker.

If this rule was really being implemented for the benefit of the shareholders, then Congress could have let each company’s shareholders opt in or opt out of this disclosure regime. Clearly, the people pushing this ratio had no interest in giving actual shareholders a veto over this racket.

Posted by Marc Hodak on September 15, 2013 under Executive compensation, Irrationality |

A pair of recent studies show that about a quarter of the compensation earned by CEOs is now paid as restricted stock. Furthermore, one of the studies notes that an increasing portion of that stock is being granted based on performance rather than automatically vested over time, and that stock price is one of the most common performance measures used to determine the number of shares granted. In other words, if the stock price goes up (or goes higher than some benchmark), then the executive would benefit from both the larger number of shares granted and the higher price per share. If the stock price goes down, the executive will get fewer shares at a lower price, or maybe no shares at all. The governance mavens are praising this trend.

There is a lot to like about ‘performance share’ plans, and stock-based stock grants provide an exceptional level of motivation and accountability for total shareholder returns over a wide spectrum of performance over time. So, I’m wondering: Why is this kind of plan legal?

Read more of this article »

Posted by Marc Hodak on August 23, 2013 under Executive compensation |

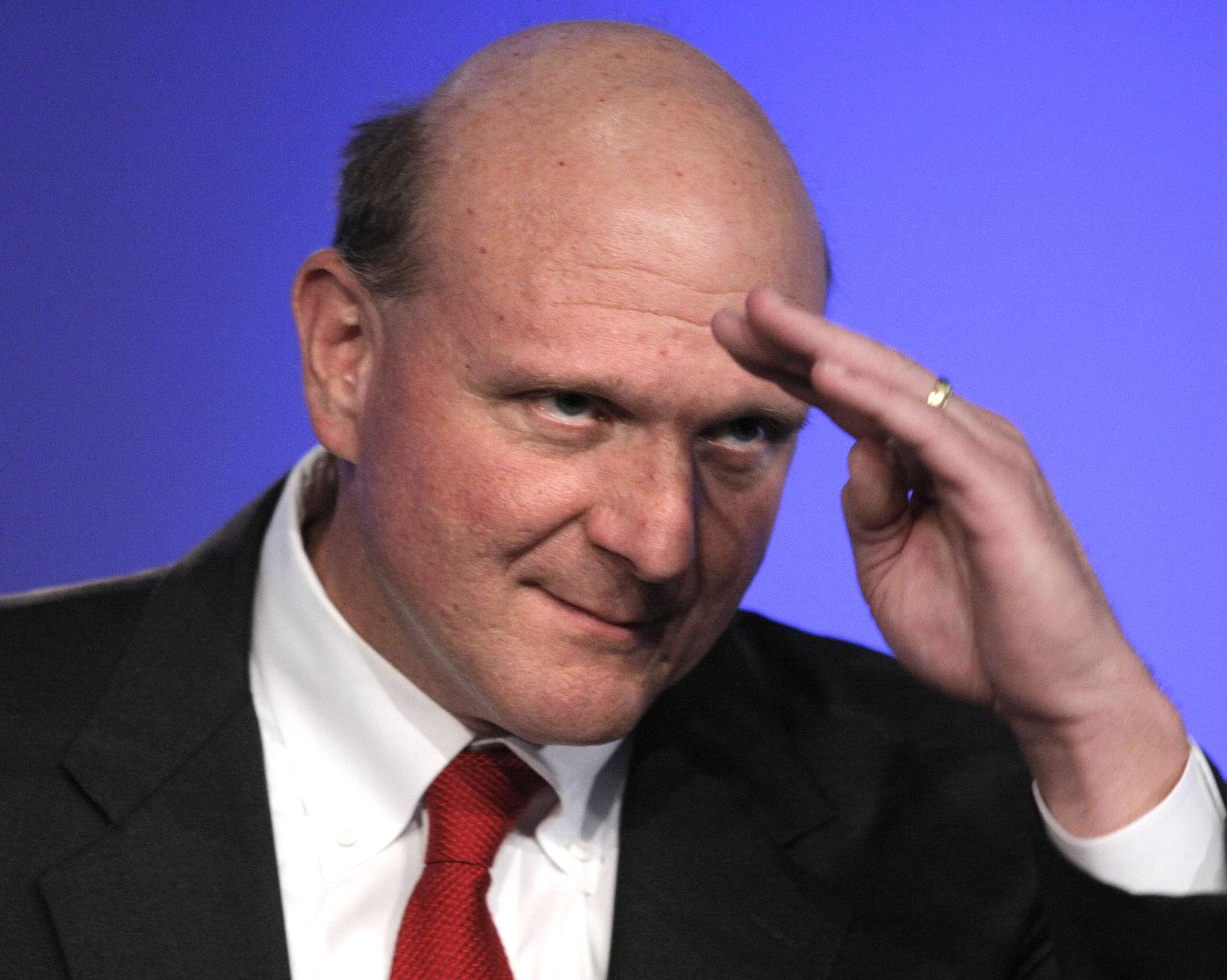

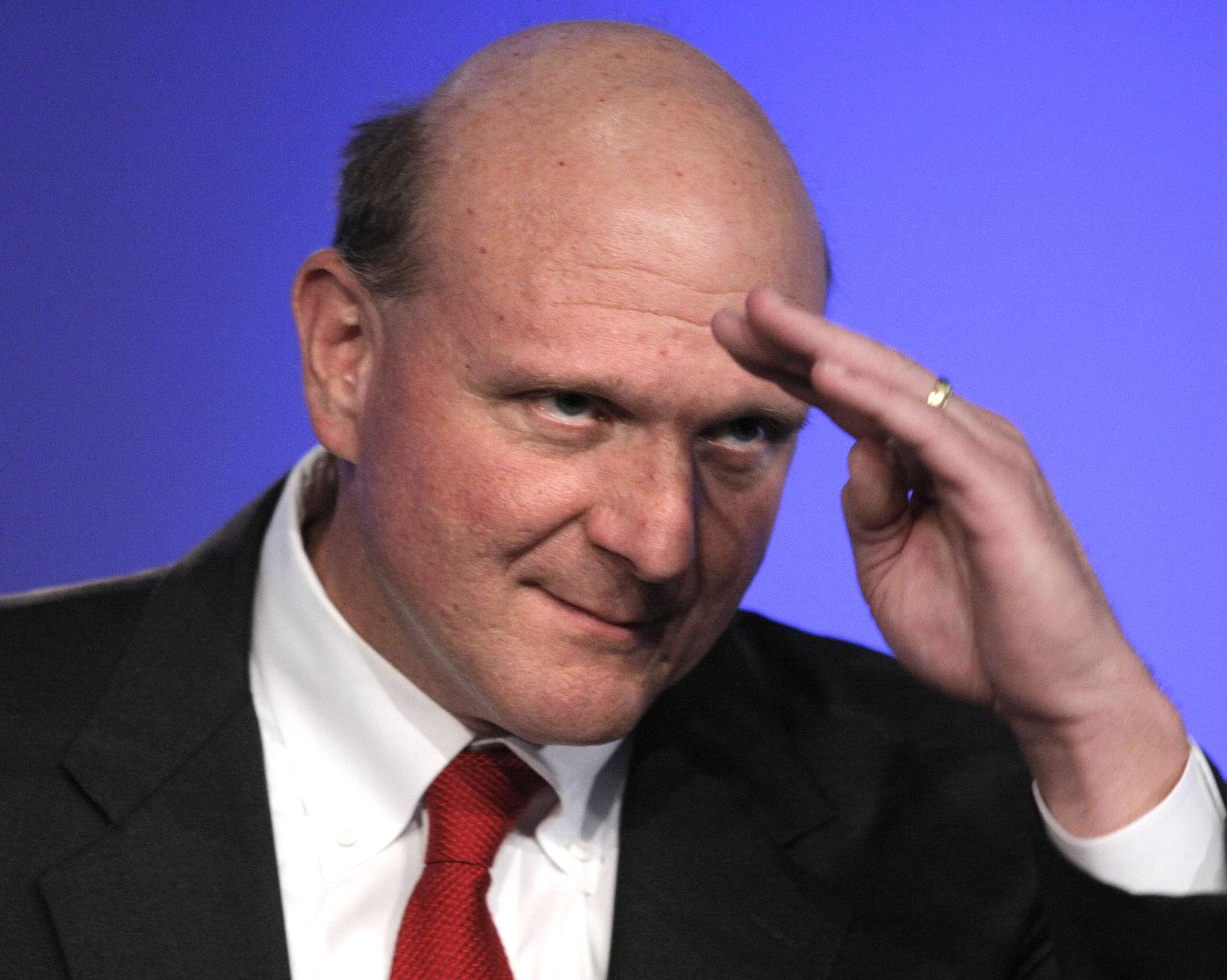

The other Steve

Steve Ballmer announced his resignation, and Microsoft’s stock price shot up seven percent. Ouch.

That investor verdict is far more damning than anything shareholders could have conveyed through a proxy vote. It tell us pretty directly what the market thinks about Ballmer or, more specifically Ballmer’s leadership relative to anyone that Microsoft is likely to hire as his replacement.

One way to read this reaction is that Ballmer has been a roughly $19 billion drag on his company. This deficiency might have been inferred by the fact that Microsoft’s stock has gone exactly nowhere* in the decade that Ballmer has been CEO, significantly underperforming the Nasdaq, not to mention its closest competitors Oracle, Google, and especially Apple. I’m sure Steve Ballmer is in for many unflattering comparisons to Steve Jobs in the upcoming weeks.

I’m not here to bury Ballmer, or to praise him, but to highlight how this coda of his tenure reflects on the value of a “typical” CEO. I often hear how a CEO doesn’t do it alone–he or she is part of a team. I often hear people questioning whether the average CEO is worth the $15M to $20M per year that they get paid, or whether any CEO “needs” the $100 million they may have gotten paid in a year of outstanding performance. I have answered these questions in prior blog posts, so I will encapsulate them here.

1) Sure, a CEO is just one person on a team, but the CEO ultimately selects and manages that team, amplifying or cancelling their talents. His or her marginal contribution is still very large.

2) Ballmer illustrates that a CEO may be worth much less than $20 million per year. Other CEOs, like Jobs (OK, I’m starting the comparisons), are worth much more than $20 million per year. The stock reaction when Jobs announced his resignation was a drop of about $10 billion, although his announcement was not entirely unexpected. So, how plausible is it that the average CEO is worth about $20 million per year? More plausible than $2 million or $200,000 per year, although the value variance around that average is obviously very high.

3) No person “needs” $20 million or $100 million or any such astronomical sum. But nobody this side of the Soviet Union gets paid according to their need. If things are working right, they get paid what they’re worth. This correspondence is never perfect, but we haven’t yet found a better way.

By the way, Ballmer earned about $1.3 million per year in salary and bonus as CEO of Microsoft, much less than a typical Fortune 500 CEO, but not out of line for someone whose personal net worth likely went up and down about $100 million a day due to his MSFT stock holdings which, as mentioned earlier, didn’t net him anything more than he started with over his tenure. In other words, alignment wasn’t an issue for Ballmer. Maybe he just decided he didn’t need any more? Maybe he wasn’t greedy enough?

* I’m being generous here by tagging the stock’s fall in his first year as an artifact of the dot-com bust.

Posted by Marc Hodak on July 28, 2013 under Executive compensation, Governance, Invisible trade-offs |

I am often dismayed by the popular response to “dollar-a-year CEOs.” These bosses give the media a feel-good story: You don’t have to be greedy. You can be a not-so-fat-cat!

Apparently it’s not just John Q. Public–several times removed from the real world of compensation governance–that buys this stuff. Just last week, a tech company CEO in a WSJ “expert” panel praised the dollar-a-year standard, and the swell guys and gals who adopt it, saying that all CEOs should be so virtuous.

These are people that are out to change the world. They are owners. They are builders. They bleed for their company and what they are creating. It’s not about the money.

His examples were Steve Jobs, Larry Ellison, Mark Zuckerburg, Meg Whitman, Larry Page. Do you see a pattern (besides all the money)?

Read more of this article »

Posted by Marc Hodak on May 22, 2013 under Executive compensation, Governance, Reporting on pay |

In yesterday’s WSJ, an article reported rising criticism of directors’ pay from institutional investors. Many of the quotes came from one such investor, T. Rowe Price.

Current pay structures don’t give directors enough of a stake in making sure the company does well, and boards need to be more creative about tying their compensation to performance, said John Wakeman, a vice president and portfolio manager at mutual-fund giant T. Rowe Price Group Inc.

“If bad people are going to be on these boards, we’ve got to stop it,” said Mr. Wakeman. “We owe it to our fund holders.”

“When you’ve gone to restricted-stock world, basically directors get paid more or less for showing up,” Mr. Wakeman said.

If Wakeman were referring to the portion of director fees paid in cash, then he would have a point about directors being paid for just “showing up,” but even that ignores the value of getting good directors to show up. Being a good director means working. In the world that Mr. Wakeman and I share, very few people beyond commissioned salespeople are expected to show up with zero guaranteed pay. Does he want directors compensated with purely variable pay?

But in alluding to “pay for showing up,” he is not referring to the fixed fees earned by directors, but to their restricted stock, which accounts for more than half of their total pay. Calling this “pay for showing up” is a curious accusation. To some extent, someone getting restricted stock compensation is almost certain of having something of value at the end of their tenure. But the value of restricted stock goes up and down with the share price. You don’t get any more performance-based than that. In other words, given both its retention and incentive characteristics, restricted stock may be the perfect compensation instrument for directors.

The point of bad people on a board is not how we pay them, but how do we prevent them or get rid of them. It may have been the writer instead of Mr. Wakeman who conflated these appointment versus compensation issues, but such a conflation does not help us determine the right way to either get good directors onto boards or to pay them.

The article also notes that some activist investors are experimenting with incentive pay programs for directors. The clear premise is that directors don’t have enough incentive in their current pay programs, which raises the question: what kind of pay package would be better than a program of fees plus restricted stock?

One can argue that the proportion of that pay mix ought to be more in favor of restricted stock than it is now, or that the stock restrictions should be more demanding, such as requiring that most of the stock be held to retirement. But as someone who has designed these things for many boards, and thinks deeply about compensation design every day, I would caution against too much experimentation. The three basic alternatives to restricted stock are:

1. A restricted stock-equivalent, such as a cash-settled stock appreciation plan that pays off exactly the way restricted stock would. I would favor such a plan only because it creates an income opportunity for those of us who design them. Otherwise, the shareholders get the same retention and alignment benefit as if they award restricted stock.

2. An alternative equity instrument, such as stock options. This would likely create an asymmetrical risk/reward profile for directors versus shareholders–the kind of thing that contributed to Wall Street’s troubles during the financial crisis.

3. A non-equity based incentive plan. This would be asking for trouble, as the Coke example in the article showed. The only body in a company than can certify achievement of performance results is the board of directors. Asking the board of directors to certify performance relating to their own pay creates an inherent conflict of interest. This is a fine recipe for either manipulation of corporate results, or the continual appearance of such manipulation. I would never institute a directors’ non-equity incentive plan for any company I advise (and have actually lost business for my refusal to do so).

The real story, here, is that pay is becoming the magic elixir for fixing all governance problems. We don’t have a significant problem with lack of alignment between directors and shareholders. We just have some companies that don’t perform well, and some of that lack of performance reasonably attributable to lax oversight by the board. Too much experimentation with director pay would only make the problems worse because it would be attacking the wrong problem.

Posted by Marc Hodak on April 22, 2013 under Executive compensation |

The actual title of the article was Regulators Get Banks to Rein In Bonus Pay, but it might have been the title of this post. The germ of this article is:

Since the financial crisis the Fed has urged banks to cap bonuses in cases where they could encourage executives to take too much risk. Before the crisis, banks erred by focusing too much on short-term profits and too little on risk when designing bonus plans for employees and executives, according to the Fed.

The Fed’s intent has devolved into policies advocating the use of measures besides profit, and the capping bonuses at something less than two times target bonuses. These two policies ignore two, basic propositions of incentive compensation:

1) An incentive to perform is indistinguishable from an incentive to cheat

2) A cap on bonuses is tantamount to a cap on performance

These policies are nevertheless being advocated despite any evidence whatsoever that they help shareholders. That is not surprising, however, since the Fed is not accountable to shareholders, but to political interests that could care less about investors.

I don’t usually offer investment tips, but here is one that is consistent with research on this matter: Invest in companies that pay for profit growth, and don’t limit how much their executives can make. In other words, bet against what the government is advocating.