Posted by Marc Hodak on October 15, 2016 under Economics, Executive compensation, Governance |

Bengt Holmstrom, a co-winner of the 2016 Nobel Economics Prize, rails against the complexity of executive pay. He’s right about that. He blames compensation consultants, but that is attacking a symptom, not a cause. The underlying cause is the proliferating regulation—formal and informal—of compensation governance. This regulation creates constraints on how Boards can design executive compensation programs. Boards rationally react to those constraints by building plans of ever-greater complexity.

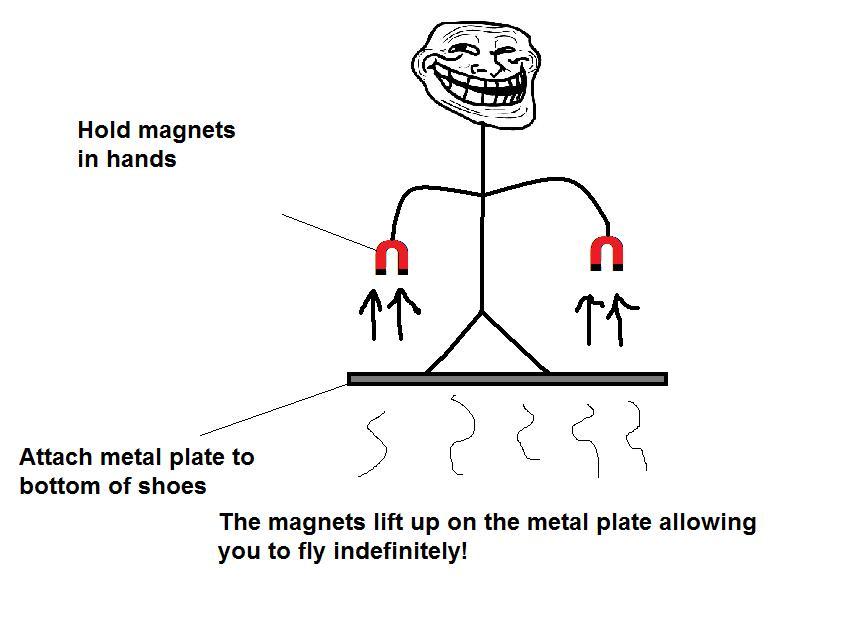

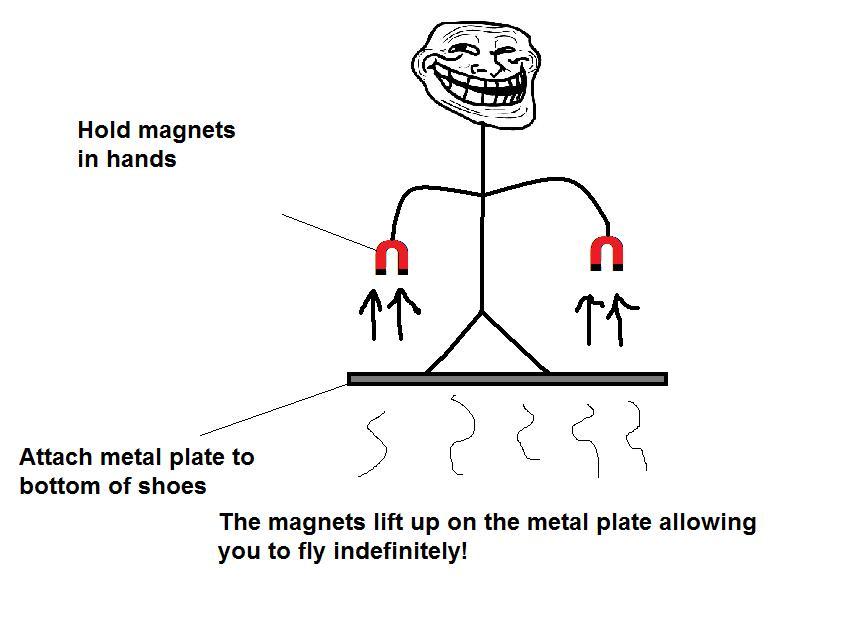

The source of compensation regulations is popular disdain for high CEO pay. The intent of the regulations is to tamp down that pay, but that’s like putting nails in a board to stop a marble from rolling down. You don’t stop the marble; you just make its path more complicated.

Nevertheless, Prof. Holmstrom is a worthy scholar, one whose research has done much to inform my discipline, even if unfortunately few practitioners have actually heard of him, or heeded his conclusions.

Posted by Marc Hodak on September 8, 2015 under Economics, Executive compensation, Invisible trade-offs, Reporting on pay |

Against The Tide

High pay is controversial because there are inherently two, generally opposed, sides to the debate. This was well illustrated in a recent WSJ article about highly paid, star college football coaches. Given the topic, it’s appropriate to label the two sides “offense” and “defense.”

Offense

This is a good name for an instinctive reaction that we all have; we are offended by other people’s high pay. It’s a natural response. The moment any of us hears that someone has made millions of dollars, our knee-jerk reaction is “who can be worth millions?” We can’t help it. We also can’t help trying to supplement that emotional reaction with logical arguments. This is almost always done via comparisons to other people’s pay.

Last year, the current Alabama [Crimson Tide] coach, Nick Saban, made $7.2 million, roughly 11 times the salary of Alabama’s president.

Messrs. Saban and Meyer make 50 times that of an average full-time professor at their respective schools; Mr. Harbaugh makes 32 times more than an average full-time professor at Michigan…

Much is made of the fact that Alabama is a poor state with a median household income of $43,253, some $10,000 less than the national average. Public funding for higher education in the state was slashed by $556 million from 2008 to 2013, a 28% drop. Mr. Saban’s salary has risen 80% since he arrived at Alabama in 2007.

What makes these comparisons compelling is that they bring the discussion somewhat closer to the scale of our pay. If we get paid much less than top college coaches, for example—a better than 99 percent bet, even for readers of the Wall Street Journal—then we get to share the outrage that these people are making so much more than we are. I mean, who are these people? Are they really any better than us?

Some people call this reaction an instinct for fairness. Some call it envy. Regardless of the name, it is the first thing that strikes us when hearing “millions.”

Defense

And that is why any explanation or justification of other people’s millions can be viewed as a “defense.”

The easiest, and ultimately only way to defend high pay is to reference its negotiated nature. People don’t get what they deserve; they get what they negotiate. This negotiation is invisible to us, a distant, unwritten prequel, by the time we are reading about something like “$7.2 million.” When we say, “I can’t believe so-and-so is being paid that much,” we are really saying one of two things:

(1) “I can’t believe so-and-so was greedy enough to ask for or accept that much,” or

(2) “I can’t believe the person paying them that much really needed to.” Both criticisms represent a kind of an arrogance, if you think about it.

On the one hand, we are accusing the person who made a lot of a moral failing that any of us would likely succumb to if we were in their position. In my experience, the people who complain most loudly about other people’s pay are the least likely to turn down a windfall were it to come their way. On the other hand, we are accusing the person who paid the salary of being stupid, lazy, or corrupt with reference to their compensation decisions. We’re calling the owners, who are generally very successful themselves, financial dolts. On its face, this seems implausible. So, the sensible thing is to first ask the people paying millions what they were thinking.

Former Alabama President Robert Witt (now the chancellor of the Alabama university system), once told CBS’s “60 Minutes” that Mr. Saban was “the best financial investment this university has ever made…”

Mr. Saban had an immediate financial impact on Alabama. In 2007 the school was closing a $50 million capital campaign for its athletic department. After Mr. Saban arrived, the campaign exceeded its goal by $52 million. Alabama’s athletic-department revenue the year before Coach Saban showed up was $68 million. By 2013-14 it had risen to $153 million, a gain of 125%. (The athletic department kicked $9 million of that to the university.) Mr. Saban’s football program accounted for $95 million of that figure, and posted a profit of $53 million.

In other words, they were thinking that offering those millions in salary would pay them back in dividends. That bet doesn’t always work, but it was clearly working for Alabama. And these owners are considering all of the revenue streams likely to be impacted by their hire, the way any professional team owner would look beyond the gate receipts and TV licenses.

Mr. Witt said Mr. Saban also played a big role in the success of a $500 million capital campaign for the university (not merely the athletic department) that took place around the time the football coach was hired…

Ohio State has benefited in a similar way since luring Mr. Meyer, 51, out of a brief retirement in 2012. The university’s athletic-department revenue was up 14% to $69 million during the season last year, one in which Ohio State won the national title. In the aftermath of the title, the school’s merchandise sales totaled $17 million, some $3 million more than the previous year. More than half of that money goes to academics.

So, the defense of high pay is that if we give the recipient a portion of his or her value to the organization, the organization will benefit. That is true whether we are talking about coaches, or players, or real estate agents, or investment bankers. Economists call this paying for the individual’s marginal revenue product, and a principle of economics is that society as a whole is generally better off if every person is paid according to his or her marginal revenue product. Paying too much is a waste; paying too little risks ‘misallocation’ of that person’s talents.

The End Game

Whether we are talking about college football coaches, professional entertainers, or corporate executives, the debate often comes down to what game you’re playing. If you’re playing the game of fairness or envy, then you simply don’t want some people to make too much more than others, regardless of the economic consequences. If you’re playing to maximize overall social welfare, then you allow people to earn a significant portion of what they make for others, and let the chips fall where they may.

One might admit to a mix (or confusion) of motives in order pursue some middle ground. But in football, at least, no one scores in the middle ground.

Posted by Marc Hodak on July 13, 2015 under Economics, History, Politics |

“We can make them sign it. What can go wrong?”

The Germans, who are normally quite astute about the lessons of history, are now acting against Greece with what looks like a vindictive intransigence that would have made Allied negotiators at Versailles nod approvingly. The Greek’s choice now appears to be between another bailout and continued harsh austerity, or default and financial collapse. Who in Europe believes that pushing Greece into desperate economic straits is good for their stability? Will it take the rise of someone much more extreme than Tsipras to make the Germans, French, and others understand what they are really getting in exchange for avoiding another haircut on the loans, and accepting any responsibility for the bad judgments of the lenders as well as the borrowers?

Greece may have another choice. Two choices, actually: an economic choice and a political choice.

The economic choice, under a rational leadership, may enable Greece to default on their outstanding debt and quickly resurrect their access to global capital markets at reasonable rates. This choice would merely require a couple of changes in their constitution. It has been done before. To see how, we need to step further into history.

Read more of this article »

Posted by Marc Hodak on May 27, 2014 under Economics, Innumeracy |

Whenever minimum wages are being debated, as they are once again, we can count on someone bringing up the old story about Ford’s $5-a-day gambit. It goes something like this:

Ford Motor founder Henry Ford revolutionized the industrial landscape when he doubled his employees’ wages to $5 per day in 1914. The pay increase allowed his workers to buy the Model T cars they assembled every day on the factory line.

Enabling workers to “buy their own product” supposedly enables the creation of a mass market, helping producers as well as consumers. But is that true? And is that how Ford benefited from his wage hike? Let’s look at the math.

In 1914, when Ford Motors instituted the $5-a-day wage, the company had about 14,000 workers making $2.25 a day, for a total wage cost of about $32 million. Ford was selling about 250,000 cars a year at about $500 per car. That’s about $125 million in total revenue. So, let’s say that ALL of the increase in wages–$2.75 per day per employee for all 14,000 employees–went toward the purchase of Ford cars. (Why that would have been impossible is a story for another time.) That would be sales of about 20,000 more cars (yes, more than one car per worker), yielding Ford about $10 million dollars more in revenue. So, the “buy-their-own-product” folks are asserting that Ford benefited by doubling his labor costs in order to increase his sales by less than 7 percent. For one year.

Nope.

The buy-their-own-product rationale is as historically mistaken as it is economically ridiculous. Ford’s stated intent in dramatically raising wages was to reduce the huge turnover his new assembly line process had created, and the high costs of dealing with that turnover. In other words, it was a bold solution to a novel production problem.

Furthermore, far from expecting any major increase in sales (i.e., from his own workers), Ford counted on having his profits significantly reduced that year as a result of the wage increase. In fact, he was gleefully counting on it. Why would Ford want his profits hurt that year? Because he was in the middle of an outrageous gambit to squeeze out his fellow investors (and new car competitors) John and Horace Dodge, and a ding to the company’s profits that year would hurt them much more than it would Ford himself. Ford, in fact, expected to realize the benefits of lower turnover in later years once his volume was greatly expanded (which is what eventually happened).

The idea that increasing your employees’ wages to enable them to buy your product is one of those ditzy notions that requires math blinders to believe. Yet the “buy their own product” argument will continue to be made because belief is more powerful than math.

Posted by Marc Hodak on August 24, 2011 under Economics |

August 26, 2011.

Ben Bernanke goes up to the podium, and looks around at an expectant crowd, every ear bent in his direction, wondering what he will announce to kick start the economy. He sees the cameras trained on him, ready to carry around the world his brilliant musings, and his expert prescription for what to do next. The global markets await.

Ben clears his throat, looks around, and begins.

“Why are you all looking at me? What the hell do you expect me to do?”

Read more of this article »

Posted by Marc Hodak on July 7, 2010 under Economics, Patterns without intention |

The first approach is counting on government to do it from the center, as reported a few weeks back:

Don’t laugh, but Uncle Sam wants to teach you how to manage your money.

Tucked into the new financial-overhaul bill that Congress is working to finish is a new Office of Financial Literacy to help consumers learn about savings, debt and credit scores.

There is an obvious irony in a debt-laden, budget-challenged government offering financial education. But there is a deeper problem: While nearly everyone agrees that Americans of all ages and income levels could be more financially astute, no one has a good plan for making it happen.

(Raising my hand.) Oh, I have a great idea! Choose me! Choose me!

Why not just ask all those government run schools to teach financial literacy alongside reading, writing, and math, and before inorganic chemistry and trigonometry. If a school really wants to go whole hog, they have only to look at a great example of what works.

Posted by Marc Hodak on June 17, 2010 under Economics |

A new symptom of financial illiteracy has been revealed by the obsession with BP’s dividends shown by politicians and the media, no doubt reflecting their readers’ sensibilities. The narrative is that BP’s shareholders should share in the suffering their company has caused by having their dividends suspended.

This attitude reflects what can only be called a pre-war (WWII) view of financial economics, an alternate world where the breakthrough insights of John Burr Williams or the Nobel Prize winning theories of Miller or Modigliani or the resulting empirical transformation of modern finance theory never happened.

On an intuitive level, it doesn’t matter to the owner of a gas station if their cash is in the till at the office or their cookie jar at home. Why would it matter to the shareholders if their cash is still inside the company supporting their share price or mailed out to them in the form of a dividend check?

Of course, the answer is it doesn’t matter.

Read more of this article »

Posted by Marc Hodak on June 16, 2010 under Economics, Invisible trade-offs |

Alan Blinder, former Vice Chair of the Fed and Princeton economist, takes that school’s reputation down another notch in his panting defense of the the government’s performance during the recent financial crisis–particularly since President Obama took office.

The second landmark was the fiscal stimulus package that President Obama signed into law about four weeks into his presidency. Originally priced at $787 billion, it was later re-estimated by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) to cost $862 billion. A huge waste of money, say the critics—even though most independent appraisals, including that of the CBO, credit the stimulus with saving or creating two million to three million new jobs…

Try to imagine any government spending a massive sum like $862 billion without creating or saving millions of jobs. More specifically, suppose peak-year spending from the stimulus bill was about $300 billion—which is roughly correct—and that our hapless government just sprinkled its purchases around at random. On average, each job in our economy accounts for about $100,000 worth of GDP. (We are a highly productive bunch!) So $300 billion worth of additional GDP should be the product of about three million more jobs. Do we really believe the stimulus produced only a small fraction of that—or none at all?

Try to imagine an economics department like Princeton giving an advanced degree for any candidate making such a silly argument.

Surely, Prof. Blinder can imagine a government like the Soviet Union spending a significant portion of their country’s GDP without producing any net jobs. Or North Korea. Even less communist countries like France and Greece who have spent public money like drunken sailors have not really created any net jobs. In fact, the amount of jobs a country creates is just about inversely related to the amount of its GDP spent by its government.

Blinder is trying to trick the reader when says “jobs.” He means gross jobs, not net jobs. If I took $10,000 from ten people, and gave it to someone to spend a year digging ditches and filling them up again, that would look like a job “created” in Prof. Blinder’s world. The fact that the $100,000 was not spent by its original owners to support jobs in dozens of grocery stores, clothing stores, car shops, etc. apparently doesn’t enter into his calculation. An economist worthy of the name accounts for such secondary consequences of the policy they are defending. (BTW – The fact that the money is borrowed instead of taxed doesn’t quite save this argument.)

The reality, of course, is that our hapless government did not sprinkle its largess at random, and it did not target its spending toward the areas of highest unemployment. It funneled much of it to its preferred constituents/supporters in the most politically rewarding way, just as any government would do.

Why would an acclaimed economist like Alan Blinder resort to such sophistry? Because the economics profession unfortunately does not distinguish between “economics” as a science, with the maddening circumspection that scientists must display in order to retain their reputations, and “economics” as advocacy, which appears to forgive the most unscientific assertions when made for a partisan cause. Blinder wrote this garbage as an advocate, not as an economist.

Posted by Marc Hodak on April 26, 2010 under Economics, History |

Reading about governance in the first villages of New England, I come across lessons that keep getting repeated, down to our time. In 1641 the English Civil War triggered an economic crisis across the ocean. It threatened to disrupt relationships and supplies from the mother country upon which the colony depended, causing a number of the colonists to either sail back to England or move south where they could create a better subsistence for themselves.

The resulting turmoil caused a sharp drop in the price of land and commodities. At the same time, with labor getting scarce, workmen were able to ask for much higher wages. Relatively larger landholders found themselves in an economic vise. So, the town fathers, made up principally of these larger landholders, decided to pass wage regulations, limiting how much workmen could charge for their labor. Here’s a sample of those rules:

Every cart, with four oxen, and a man, for a day’s work 5s.

All carpenters, bricklayers, thatchers 21d./day

All common laborers 18d./day

All sawyers, for sawing up boards 3s./4d. per 100

All sawyers for slit work 4s./8d. per 100

The grandees who argued in favor of this price list no doubt justified it by arguing (a) it was for the public good, (b) no worker should profit from economic turmoil, (c) no one was worth 10 s. per day, (d) it’s good to spread the pain, and (e) given that these limits would be imposed on relatively poor people living at the edge of civilization between an inhospitable wilderness and a gaping ocean, “where else could they go?”

For you economics majors out there, what was the predictable outcome of these wage controls?

Read more of this article »

Posted by Marc Hodak on April 21, 2010 under Collectivist instinct, Economics, History, Movie reviews, Politics, Reporting on pay, Stupid laws |

The IMF is pushing for a bank tax:

[T]o pay for the costs of winding down troubled financial institutions, the IMF proposed what it called a Financial Stability Contribution”—a tax on balance sheets, including “possibly” off-balance sheet items, but excluding capital and insured liabilities. That tax would seek to raise between about 2% to 4% of GDP over time—roughly $1 trillion to $2 trillion if all G-20 countries adopted the tax.

On top of that, the IMF proposed that nations to adopt what it called a Financial Activities Tax, levied on the sum of profits and compensation of financial institutions. That would be paid to a nation’s treasury to help finance the broader costs of a financial crisis…

The IMF said that a nation didn’t need to put in place a specific resolution authority. Instead, the tax money could go to general revenues and used in case of financial crisis. But the IMF warned that the money would be spent by the time a problem arose.

OK, so let’s see how this would work. Congress levies massive new taxes on every major bank. Congress would then spend that money on…stuff. A financial crisis hits, and certain TBTF banks get into trouble. Congress bails them out, having to borrow gobs of money to do so because the tax revenues that were nominally for “Financial Stability” were in fact spent on…stuff.

So, how is this different from what happened last time? Hard to see. Does it do anything to reduce the systemic risks that regulators insist were at the root of the last crisis? No. Does it strengthen the banks to make them better able to weather such a crisis? Not likely when so much money of their capital–enough to raise between 2% to 4% of GDP–is being sucked out of their coffers. At least if the money were being held in a trust fund instead of dumped into general revenues, it would be there for frenzied politicians to disburse based on the rational workings of the government. But, of course, the money will not be there. It will have been spent not to support the financial system, but to support the reelection of incumbent politicians–the most short-term actors on the planet.

Oh. Yeah. THAT would be the difference.

So the lesson from all this appears to be: When it comes to a justify raising taxes, any excuse will do.