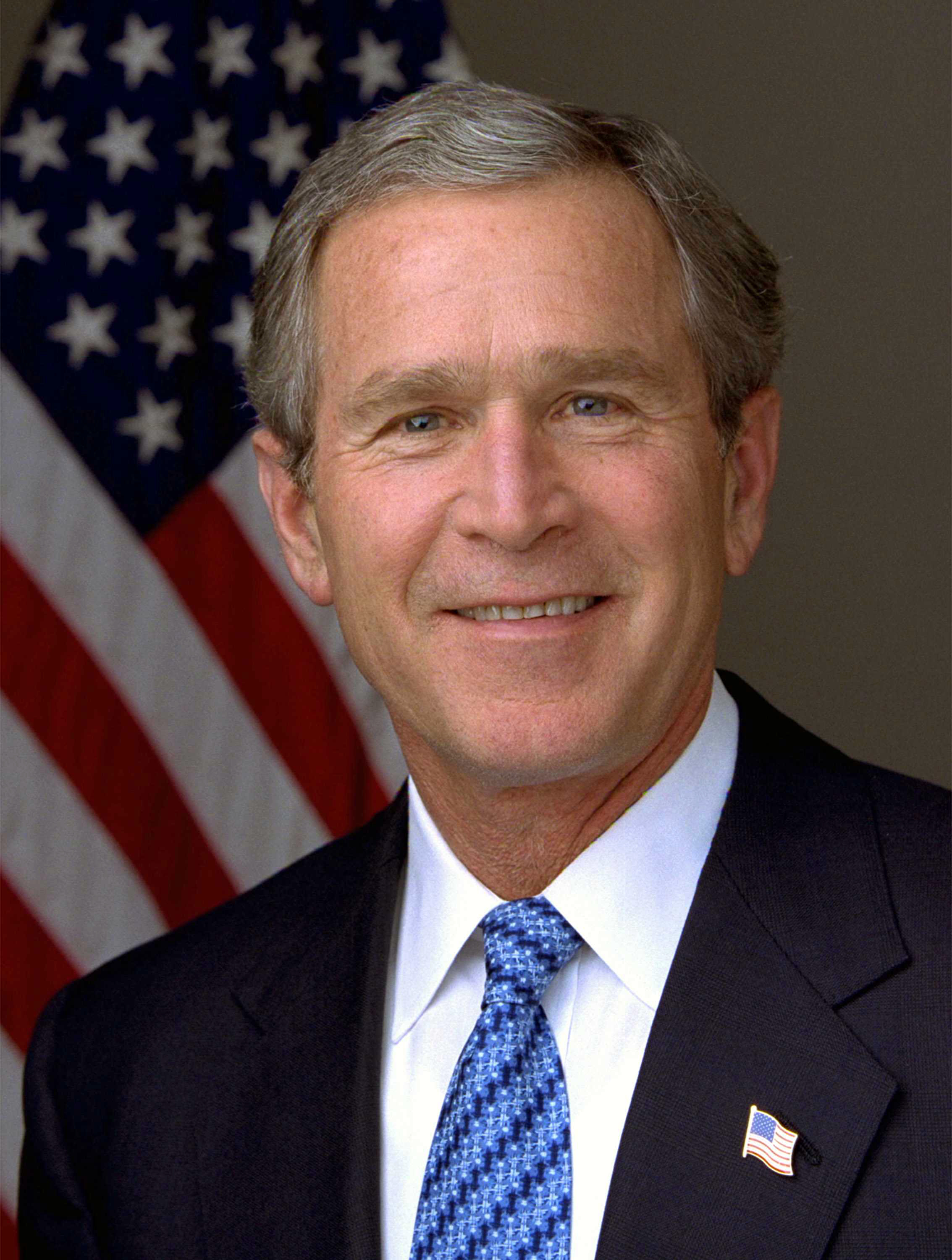

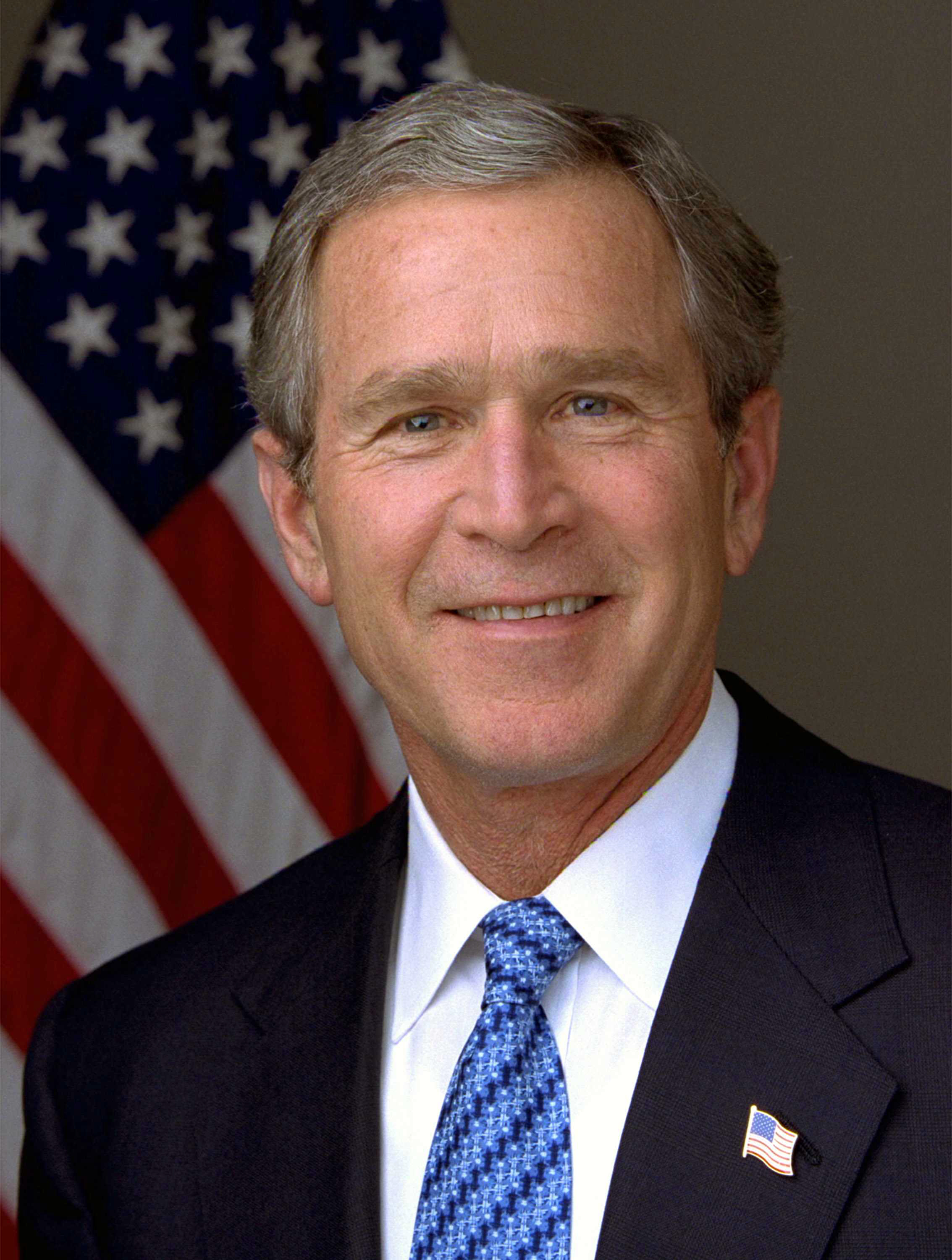

Posted by Marc Hodak on August 7, 2007 under Collectivist instinct |

A former KGB officer suggests that international lack of regard for our president is merely a reflection of our own disrespect for him. He recollects for us a youthful impression:

My father spent most of his life working for General Motors in Romania and had a picture of President Truman in our house in Bucharest. While “America” was a vague place somewhere thousands of miles away, he was her tangible symbol. For us, it was he who had helped save civilization from the Nazi barbarians, and it was he who helped restore our freedom after the war — if only for a brief while. We learned that America loved Truman, and we loved America. It was as simple as that.

So, his remedy is to stop bashing our own presidents. We should summon just enough propaganda to squelch public disdain about our leader in order to strengthen other’s perceptions about him.

Aside from the principled and consequentialist qualms I’d have about the level of propaganda that would be needed to make Americans feel good about someone like Bush (or any recent president, not to pick on W), I wonder about the value of doing so. Clearly, it helps to achieve “national” objectives for everyone to be behind a leader proposing them. But are national objectives all they’re cracked up to be?

I’m also skeptical about the psychology of former-Soviets, even those of good will towards America. I have had many friends from the former Soviet Union. They have been uniformly smart people, some of them quite brilliant, but nearly all of them possessing a peculiar blind spot with regards to propaganda and the associated freedom of the press. I know that to them, my “knee-jerk” defense of an unfettered press, even one prone to printing lies, seemed equally peculiar. So, when I expressed my doubt about the long-run efficacy of propaganda, I would use my Russian friends themselves as Exhibit A: you won’t find a more cynical people on earth than Russians, and I don’t think it’s genetic. Furthermore, no amount of propaganda got the Russians to forget about the Beatles or blue jeans. Decades of hero worship nurtured by propaganda did not prevent Lenin’s statue from toppling all over the communist world, including in cities named after him. In the long run, I don’t think W’s image can be resurrected with fawning press coverage. If anything, presidents like Lincoln, FDR, Kennedy, and Reagan get far better press treatment today than they got in their own day.

The most disturbing thing about this Russian’s nostalgic recollection, however, is his grown-up expression of a child’s most collectivist impulse–hero worship. Our press already possesses the most annoying tendency to credit collective effort to a single individual, even as it subtly undermines the value of the individual in nearly every other way. They aggrandize individuals because their readers relate to individuals, not ephemeral forces. We buy celebrities, not concepts. The press certainly has an interest in selling us the notion that W’s daily schedule is newsworthy, or that it matters why Brad broke up with Angelina. Even if idolatry is good business in catering to human nature, though, I really don’t see the virtue of supporting it as a matter of public policy.

Posted by Marc Hodak on July 19, 2007 under Collectivist instinct |

Every now and then, I figure that maybe Europe is at a stage where it might begin keeping America honest. They may look over here at our freedoms, and decide they don’t want to be collectivist also-rans anymore, that they’re ready to step up to the challenge of being the place where the world wants to live, and reduce taxes, and reduce regulations, and spread those human rights like warm Nutella on a baguette.

Then they pull sh*t like this.

Read more of this article »

Posted by Marc Hodak on July 3, 2007 under Collectivist instinct |

Check out this lede:

The government regulates real-world commerce and crime. But as virtual worlds become more complex, should the government regulate virtual life?

Did it come from The Onion or the MSM?

Posted by Marc Hodak on June 17, 2007 under Collectivist instinct |

A recent Sun article includes this tidbit:

Governor Rell of Connecticut, who is considering a medical marijuana bill that lawmakers sent to her desk earlier this month, has also given mixed signals about her position. She has said it’s important to help seriously ill people alleviate their pain, but has expressed fear that legalizing the drug would undermine the message that recreational use of marijuana is dangerous.

So, the Governor begins with a well-worn lie. In fact, recreational use of marijuana is no more dangerous than recreationally driving around town, possibly much less so. She then continues with the awesome hubris of power: Who is Governor Rell to make trade-offs for seriously ill people trying to alleviate their pain vs. the “message” conveyed by legalizing the drug? It’s legal to clog your toilet with tennis balls, to drink red ink from a pen, and to fill one’s underwear with polyester carpet remnants. What does that say to the people? To our children?

Politicians, get over yourself. Realistically, the only people likely to pay attention to your moralistic messages about how they should live their lives are people who are smoking something.

Posted by Marc Hodak on June 13, 2007 under Collectivist instinct |

On our flight back from Switzerland, our airline showed a segment from CBS���s 60 Minutes. In my (much) younger days, I was continually amazed at CBS���s capacity to expose human cupidity and folly week after week. How could they do it? So, I finally got an answer���they invented it. And the viewers believe it, as I did before I got an economic education.

This story was about the awesome power of Big Pharma to undermine our democracy. The context was the passage of the Medicare prescription drug plan without the ability of government to negotiate drug prices. The blame for this was placed on Big Pharma’s lobbying spending. If I were quite ignorant about this issue, I would have been awed by this story. Instead, I was awed by what was left out:

�Ģ The pharmaceutical industry, instead of being portrayed as creating a profitable new market for its drugs, could have been seen as acting defensively to protect their profits from a major change in how drugs are distributed in this country.

�Ģ The prevention of a government buyer���s cartel (for which Big Pharma was heavily criticized in this report) might have been worth it for reasons other than preserving drug company profits.

�Ģ The power of lobbyists and the revolving door between Congress and lucrative lobbying opportunities is not owned by Big Pharma, or Big Business generally.

Instead, the CBS reporter was shocked, shocked that all these Washington people were following the money. I was shocked not so much by CBS’s perspective as by how completely one-sided was their presentation. Their unstated premise was that government should be free to use a certain segment of the population (e.g., those involved in producing drugs) to do what is ���right��� (according to CBS���s, selling drugs cheaply enough to undermine their profits), however that certain segment should not so aggressively resist being used.

Even taking the story at face value, a more realistic remedy would be to make government less attractive to all this wealth and influence by reducing the amount of government interference in the economy. But long before anyone could make such a point on a show on CBS, you’d hear the tick, tick, tick, tick, tick…

Posted by Marc Hodak on May 30, 2007 under Collectivist instinct |

Chicago, that is, where I’ll be the next couple days. I hate cigarette smoke. When I was growing up, I nagged my smoking dad so much about the smell that he finally quit (just as I was going to college). If I was driving with him and he wanted to light up, I would make him roll down the window an inch. Even if it was sleeting. (I figured out that one inch was all that was needed to neatly suction out the smoke of a cigarette close to the window of a moving car.) Even then, I’d complain about being to able to smell it. I was a total bastard about the smoke. I just seize up when I smell cigarettes. I literally can’t breath around it. I look for the closest exit so I can catch my breath. I think it has to do with my lung operation as an infant. I really hate cigarette smoke. In fact, there is probably only one thing I hate worse than cigarette smoke: sanctimonious, paternalistic, do-gooding legislators subjecting an entire major city to the same bratiness visited on my poor dad.

Posted by Marc Hodak on May 25, 2007 under Collectivist instinct |

The WSJ presents a great example of this:

Sen. Hillary Clinton took the first step toward outlining her health-care agenda, suggesting a range of cost-cutting moves that she says would wring $120 billion of savings from insurance companies, drug makers and the rest of the health-care system.

She will draw from those savings when she details a much-anticipated plan for providing health coverage for the uninsured later this year.

Translation: Hillary is inventing savings now that she can spend later.

The “savings,” of course, are the product of an infantile imagination, the kind of things that kids dream up who have never actually struggled with the reality of turning managerial initiative into market-tested products or services when they say things like, “I’ll invent a laser that gets rid of cancer” or “I’ll invent shoes that never go out of style.” You don’t want to discourage the tykes, but you’re not about to give them a hundred billion dollars to test their cute theories. But Dr. Hillary will no doubt convince millions of voters that she should be given that access to our tax dollars because she has the cure to what ails them.

The spending–that will be very real. Hillary actually has a track record on that one.

Posted by Marc Hodak on May 20, 2007 under Collectivist instinct |

Today’s lesson is that China represents “A Shining Model of Wealth Without Liberty.” Here is author James Mann’s breathless warning:

This all adds up to a startling new challenge to the future of liberal democracy. And the result is ominous for the cause of freedom around the world. China’s single-party state offers continuing hope not only to such largely isolated dictatorships as Burma, Zimbabwe, Syria and North Korea but also to some key U.S. friends who themselves resist calls for democracy (say, Egypt or Pakistan) and to our neighbors in Cuba and Venezuela.

That’s his story–a snapshot comparison between nations that pretty cleanly ignores any trends, such as the growing difference between China and the other dictatorships cited by the author, or the increasing similarities between China and the Western countries it is catching up with. All Mann sees is the politics. Sure, he notes that, “The ruling party allows urban elites the freedom to wear and buy what they want, to see the world, to have affairs, to invest and to profit mightily.” But he sees this freedom merely as a sop by the party to bribe the elites into complacency, rather than a possible source of their growing national wealth.

Here is another view.

“Everyone said the fall of the Berlin Wall would herald the spread of democracy around the world. I think the experts and pundits got it wrong. Democracy has made inroads, to be sure. But what really took off was the spread of capitalism. It was the opening of markets that has made the most difference to the most people, lifting millions out of poverty.”

That was Stanley O’Neal, CEO of that petty bourgeois institution, Merrill Lynch.

Which view do you think holds more merit?

Posted by Marc Hodak on May 17, 2007 under Collectivist instinct |

Less than 24 hours after predicting the end of large-scale experiments in central planning, I got a vivid reminder of what is going on in Venezuela.

“We are building socialism and fighting capitalism!” says co-op leader Juan Nava, standing amid wooden shacks on what used to be Mr. Lecuna’s land.

Much of this story could have been directly lifted from the accounts of collectivization in Russia, Hungary, China, and North Korea.

The government bills land reform as a way to make Venezuela self-sufficient in food. But so far, the effect has been to undercut production of beef, sugar and other foods, as productive land is handed to city dwellers with no knowledge of farming. Established farmers and ranchers, fearing their land may be seized next, are cutting investment in their operations to a minimum.

The chaos in the countryside has contributed to shortages in basic items like milk and meat, a paradox in a country enjoying an economic boom traceable to high oil prices.

Collectivizing property is a lot like a civil war between rich and poor, with the government backing the poor. As in all wars, the first victim is truth.

Mr. Ch?�vez blames the shortages on “speculation” by distributors and producers. Agriculture Minister Elias Jaua recently called a news conference to deny there’s been any decline in food production during the eight years of Ch?�vez rule.

This lie goes all the way down.

Co-op members have uprooted about 540 acres of sugar cane planted by the former owner, Mr. Lecuna. The co-op’s Mr. Nava, a wiry former construction worker in plastic sandals, says members have planted 60 acres of plantains, a figure he ups later in the interview to 170. Lecuna ranch hands say it’s 10 acres at most.

The government stopped supplying agricultural data in 2005. Does anyone believe this time things will be different? Here is an open letter signed by dozens of academics and NGOs observing Chavez from the outside.

When we see a nation rising up and thwarting all attempts to derail people’s government, the inspiration and motivation we derive is inexpressible.

More than they know.

Posted by Marc Hodak on May 8, 2007 under Collectivist instinct |

Today’s New York Sun had an article about The Beacon School’s problems with the government regarding unauthorized class trips they took to Cuba. I can sympathize with their silly entanglements the government, but not with their ultimate motivation:

A 2004 graduate of Beacon, David Goodman, dismissed claims that the teacher who took students to Cuba this year, Nathan Turner, was anti-American, but said he taught history with a ” Howard Zinn kind of look at the world.”

“He is off the charts liberal,” Mr. Goodman, who said he has liberal views, said. “A lot of the school is like that. I came out of there feeling that it was too leftist and they weren’t giving you enough of a general history.”

One might think this is par for the course at a New York public school, but my son jokes about having to read Howard Zinn in his private school, as well. Some joke.

Most New York liberals will say that history can’t be taught without a political slant, much the way that creationists don’t think biology is a “value-free” science. Objectivity is impossible, they figure, so you might as well offer a perspective that is “right” (as in “left”). My son’s school readily admits that they offer an “alternative” (read “left”) perspective on history, but they say they expect their students to challenge it. I will grant that they allow students to challenge their perspective, but to “expect” your average New York high school student to challenge a teacher’s liberal slant on a subject is, I think, hysterically disingenuous.

Read more of this article »