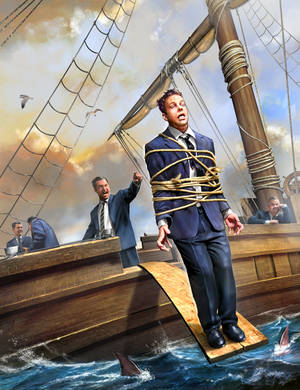

Ticking off the sharks

Hey you out there: Just kidding

Let’s say that you hire a captain for your ship, and for, say, tax reasons, decide that instead of running things from the bridge he should run things from the plank. You warn him that if anything goes wrong, he goes into the drink. But rough weather comes along, and you decide you still need him, so you don’t push him over the edge. At this point, you’ve hurt your credibility and pissed off the sharks.

That appears to be what is happening as activist investors increasingly get into the game of second-guessing corporate bonus plans. On the plus side, these shareholders are digging much deeper than the typical, diversified institutional investor possibly could. Marathon Partners, for instance, is criticizing Shutterfly’s plans that reward growth without assurance that it is value-added growth, which looks like a valid criticism.

But that doesn’t mean that activists investors necessarily know more than the boards they are criticizing:

Jana Partners LLC, which recently took a $2 billion stake in Qualcomm, has urged the company to tie executive pay to measures like return on invested capital, rather than its current yardsticks of revenue and operating income, according to a Jana investor letter. Such changes “would eliminate the incentive to grow at any cost.”

Yes, it would. But return on invested capital could instead create the opposite incentive, i.e., a bias against value-added investment. (If the investors really knew what was what, they would more likely require economic profit as the compensation metric.)

Although companies should generally be given the benefit of the doubt about their plans, they don’t do themselves any favors by trotting out the specter of retention risk when discussing variable compensation. Yet we often hear companies say, or using code words to the effect of, “Hey, we have to be careful that our incentive plans aren’t too tied to performance, because if they don’t pay out, we might lose key talent.”

Notice to Corporate Boards: Nobody buys this explanation.

And, by the way, if your variable compensation plan creates retention risk when it doesn’t pay out, then your compensation program is too weighted toward variable instead of fixed compensation. In other words, your salaries are too low and your target variable compensation is too high. In a well-designed plan, salary should cover the minimum amount of pay that would be needed to keep your executives around when your company is performing poorly.

Alas, too many corporate incentive plans are poorly designed, but not for the reasons usually toted up. These plans are a mess because the most important incentive of all is the incentive created by Section 162m of the tax code to underweight salary and overweight variable compensation. That puts public companies in a bind when incentive plans don’t pay off, which is clearly (and predictably) a recurring problem.

In other words, companies may be wrong-headed for conflating alignment issues with retention issues when arguing for slack in their bonus plans, but they come by this wrong-headedness honestly; it is a logical reaction to the unintended, deeply perverse encouragement our tax laws.

Fortunately, an increasing number of companies are starting to ignore the 162m salary limits. They are realizing that the harm that higher salaries may cause their shareholders in the form of higher taxes is easily outweighed by the benefits of more rational ratio of fixed vs. variable compensation for their management, one that militates against the real retention issues that too much compensation risk might cause.