Allowing bad bets to fuel progress

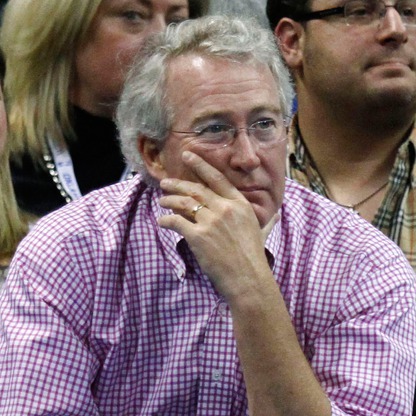

Aubrey McClendon, former CEO of Chesapeake Energy Corp. (which, as far as I know had nothing to do with the bay near where I grew up), is pulling in billions in new capital via his American Energy Capital Partners LP. The partnership will have some unusual governance features:

American Energy Capital also disclosed a range of potential conflicts of interest. The sponsors can favor their own interests over those of investors. In addition, the partnership may invest in oil and gas properties where Mr. McClendon’s firm has interests. Mr. McClendon’s management group won’t owe a fiduciary duty to the partnership, according to its registration statement.

Now, would I buy into a partnership with such conflicts? Probably not.

Would I prohibit anyone else from buying into such conflicts? Definitely not.

This partnership may or may not prove to be as good a deal for its investors as Chesapeake was for theirs. I would leave it to others to discern the bet they are making. But I would not prevent them from making their bet. And once they buy into this partnership, I would not favor the government forcing a change to the rules they bought into for the sake of “good governance.”

If all this makes sense to you, and I know it won’t to everyone, then you should be disturbed when public companies are forced to reform their governance through a federalization of corporate rules that supersede their charters. We can’t know that such “reform” will enhance the returns of outside shareholders; no governance regulation adopted by Congress over the last couple of decades had any empirical support that it would actually help shareholders, either before it was adopted or after it was implemented. But we do know that the reforms will cost every company in three ways:

(1) The Compliance CAFE (Corporate Advisers Full Employment)

(2) The occasional cost of sub-optimal decisions because of decision-making constraints created by the rules, i.e., unintended consequences

(3) The costs of lawsuits alleging a breach of the rules, regardless of their actual breach, because it is often less expensive to settle these suits than to fight them and win, i.e., the Plaintiff Lawyer’s Tax

This is not to say that we shouldn’t have any rules with regards to corporate governance. But I would suggest that the rules agreed upon by the original parties to the transaction should be given much more of the benefit of the doubt than those dreamed up by a meddling Congress. Even bad bets contribute to our progress.