Posted by Marc Hodak on July 30, 2009 under Patterns without intention |

Here is one of the best articles I have ever read about health care. It probably could have only been written by a doctor.

The article basically asks why the average cost per patient could be twice as high in one town versus another town in the same state with similar demographics and culture, as well as similar medical outcomes. The author looked at all the usual suspects: treatments, technologies, and torts. The culprit turns out to be all three–overutilization of expensive treatments. This is not necessarily driven by fear of torts, but that doesn’t help. The more expensive places that prescribe more tests and treatments don’t tend to have better patient outcomes. In fact, they tend to be worse because every treatment has risks as well as benefits, and it’s quite possible for unwarranted treatments to have a net cost in public health.

When he asked why certain places were more expensive, it unsurprisingly came down to the prevailing incentives of different models of health care practiced in different towns. In the high-cost model, physicians focused on revenue maximization by looking at the patient as a revenue source. In these environments, which evolved over time to become the culture of medicine as it’s practiced in that area, doctors tended to over-prescribe tests and treatments where judgment allowed (which covers a lot of illnesses), often referring patients to facilities in which the doctors had a financial interest. The lower cost, higher quality models were less individualistic. The doctors worked as a team, easily shared information, and got paid salaries in (generally) non-profit organizations. They were content to not maximize their personal profits as long as they were comfortably paid and allowed to act as professionals.

The author was agnostic about most of the things bandied about in today’s health care debate. It doesn’t matter if the government or private insurers are paying for treatments. The doctors are (properly) in control. If they are intent on gaming the system, they can game it regardless of who is paying. Doctors in systems built around putting their patient’s interests first can work quite well with any payers, although they will actually save more money by being given the discretion to spend what they think is appropriate. The idea of having the patients bear more of their own costs was pooh-poohed as nonsense. As one doctor asked:

“I’ll do three vessels for thirty thousand, but if you take four I’ll throw in an extra night in the I.C.U.”—that sort of thing?

The bottom line is that the current level of waste in the high cost portion of our health care system is unsustainable. Worse yet, communities are migrating from the more effective, efficient, collaborative system toward the more individualistic, wasteful, and profitable model. The key (and this may be my conclusion more than the author’s) is to figure out a way to reward the more collaborative, higher quality, lower cost, model so that it is actually the more profitable as well.

Read more of this article »

Posted by Marc Hodak on under Executive compensation, Reporting on pay |

Andrew Cuomo, Attorney General and Chief Compensation Scold of New York, raises his pitchfork once again with a report “No Rhyme or Reason,” condemning Wall Street’s “bonus culture.” The most damning piece of evidence?

Bonuses paid to executives at nine banks that received U.S. government bailout money in 2008 were greater than net income at some of the banks.

This is only surprising if you think of bonuses as something other than commissions based largely on net revenue, or perhaps net income from profitable divisions that likely saved their firms from bankruptcy.

The WSJ offers this puzzling assessment of the report:

The report is part of Cuomo’s investigation into the causes of the financial crisis. Not surprisingly, that investigation led to Cuomo’s office examining the compensation practices in the U.S. banking system.

Not surprisingly? The reason Cuomo’s investigation into compensation is not surprising is because he’s obsessed with Wall Street pay. A Cuomo investigation into the mating habits of pigeons would have led him to a critique of bank bonuses. In fact, Cuomo’s report does not even pretend to provide the slightest link between compensation practices and the financial crisis. I’m not saying there is no linkage to be made; this report simply provides none.

Read more of this article »

Posted by Marc Hodak on under Collectivist instinct, Executive compensation |

Well, we have Barney Frank:

You get hired for this very prestigious job and you get a salary, and now we have to give you extra money for you to do your job right?

This puts Mr. Frank to the left of Albert Shanker, militant union leader of the United Federation of Teachers, and Nikita Khruschev, leader of the Soviet Communist Party.

His use of “we” might be viewed as a sense of financial services companies under TARP being an arm of the U.S. government. But in the context of his proposing to expand compensation regulation to non-TARP firms, “we” can only be interpreted as evidence of his collectivist mindset, as if the bonuses paid to executives comes from the public at-large.

Posted by Marc Hodak on July 29, 2009 under Executive compensation, Practical definitions, Reporting on pay |

Congress is trying the belt and suspenders approach to keep the market from having another meltdown as we experienced last year. The belt is tighter controls at TBTF firms. The suspenders are the elimination of perverse incentives.

The thing is, if you want to eliminate perverse incentives, you have to know what they look like. According to an Equilar survey, here are some of the questions that companies are considering as they examine issues of excessive risk:

- Are we over using stock options?

- Do our incentive plans promote short-term thinking?

- Do we have the right mix between short and long-term goals?

- Do large maximum bonus opportunities promote risk taking?

- Are we using overly aggressive performance goals?

- Do our bonus plans focus on too narrow a set of goals?

- Do we have the right mix between fixed and variable compensation?

Six of these questions are sensible. One sticks out as completely bizarre to an incentive expert: “Do large maximum bonus opportunities promote risk taking?”

Of course they do. Is that supposed to be a bad thing? Entrepreneurs have unlimited bonus opportunities–thank goodness.

The question of a maximum bonus opportunity is simply the wrong question when talking about reward systems. The question they should be asking is whether steep bonus opportunities are combined with zero bonus opportunities. All the governance risk faced by a company is in the area where the participant would earn no bonuses unless they can get up into the green zone of bonus payouts with an all-or-nothing, double-down, longshot bet.

So, guess which of those questions most congressmen view as the most critical in determining “excessive compensation risk?” Yep, the risk that business executives might get paid too much.

Unfortunately, the reporting on the proposed regulation of compensation risk doesn’t even bother to define what “excessive risk” means at all, instead focusing on the political considerations of supporting or opposing any bill that purports to “contain” the excesses.

Posted by Marc Hodak on July 27, 2009 under Executive compensation, Politics, Reporting on pay |

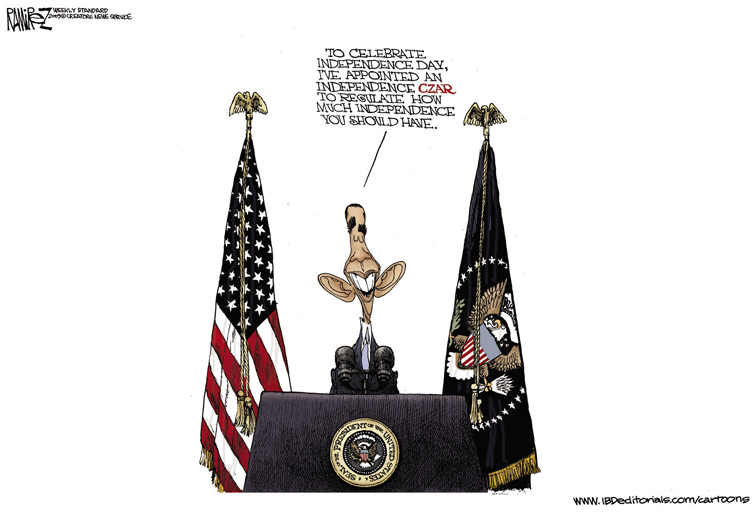

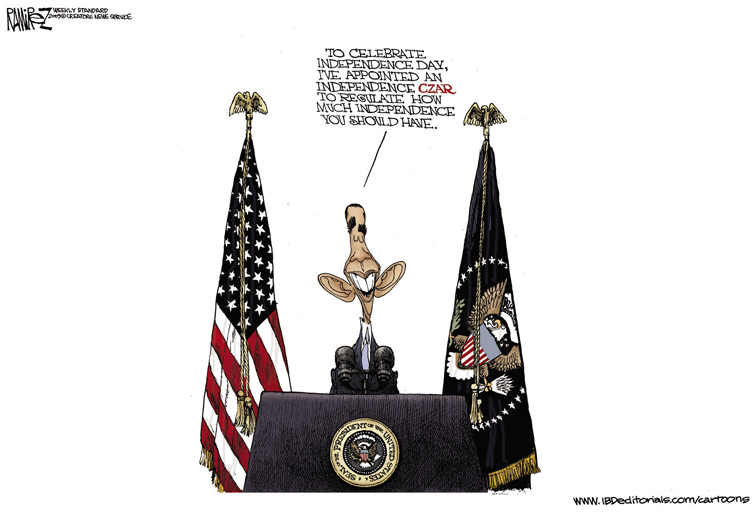

This paragraph says it all:

With public anger high over the rich pay packages awarded to some financial executives, Mr. Feinberg must walk a fine line between curbing pay at companies benefiting from taxpayer funds while not squeezing compensation so hard that it hurts the ability of companies to lure talent.

Mr. Feinberg is nicknamed the “Pay Czar,” no doubt because the Czar was such an inspiration in making the right trade-offs between populist demands and economic needs.

The irony is that Feinberg’s grandparents, like my own, may very well have been folks who escaped the Czar’s anti-semitic pogroms in the early part of the last century. We wouldn’t dream of nicknaming to Feinberg an “Oberfuhrer.” Perhaps a Commissar, Sotto Capo, or Underboss might be just as good. If not, why do so many people consider a ‘czar’ such a desirable thing in a free country?

Sounds good to me

Other Michael Ramirez cartoons

HT: Mike Perry

Posted by Marc Hodak on July 25, 2009 under Executive compensation, Politics, Reporting on pay |

It appears that Citi is on the hook for $100 million to the head of their Phibro division.

A top Citigroup Inc. trader is pressing the financial giant to honor a 2009 pay package that could total $100 million, setting the stage for a potential showdown between Citi and the government’s new pay czar.

The New York Times and Wall Street Journal, who would consider it well beneath them to publish front page stories about Jennifer Aniston’s romantic travails, have no qualms regaling the mob with stories about big dollars going to unpopular executives–the MSM’s version of porn for the business pages, which they peddle in the brown paper bag of “governance issues.” The government is easily embarrassed by these big dollar stories, which sets up “the showdown.”

So, am I suggesting that Andrew Hall, the guy in line for this bonus, is worth $100 million a year? No, I’m not. I’m sure he neither needs or deserves this princely sum. I’m simply suggesting that he should get what his contract says he should get.

A former official recently told me, “hey, contracts get challenged and renegotiated on Wall Street all the time, so why are you so upset when the government is doing it?”

I’m not upset when the government does it the way private firms typically would. A Wall Street firm renegotiates contracts quietly, to avoid the perception that they take their agreements lightly. No bank, however “powerful” they may be, could keep their doors open a fortnight if they could not be counted on to keep their word on a deal.

In contrast, the government uses these public spectacles to flaunt its disrespect for contracts, standing in a champion’s pose before the cameras, ignorant or uncaring that their knock-out is a blow to the rule of law.

Read more of this article »

Posted by Marc Hodak on July 22, 2009 under Collectivist instinct, Executive compensation, Politics, Scandal |

Missouri state's HR department

The nice people at MOSERS, the Missouri state pension fund, had a bonus plan. They beat their targets, earning their bonus. The Governor and legislature denied them their bonus.

Governor Jay Nixon called $300,000 in bonus payments to the 14-member staff of the Missouri State Employees’ Retirement System (MOSERS) “unconscionable.”

Unconscionable? What happened?

MOSERS’ incentives are based on a five-year cycle. The bonus payments paid this year were based on fund performance from January 1, 2004, through December 31, 2008. In that period, says [Executive Director Gary] Findlay, MOSERS had an overall return of 3.9% compared with its benchmark of 1.8%. (the benchmark is the performance of the asset allocation if it were invested passively).

The difference to MOSERS between a 3.9% rate of return and a 1.8% rate of return over that period, points out Findlay, is $600 million. So, the MOSERS investment staff added $600 million in value to the fund’s assets for bonus payments of $300,000, which is 5/100 of 1%.

So, tell me again, why did the politicians hose the MOSERS fund managers?

[Chairman of the legislature’s pension committee, Senator Gary] Nodler argues that payment of bonuses makes no sense in any year in which the fund experiences no actual growth. When the fund loses money, he says, then there is no money from which to pay the bonuses except to go into current assets. And that, he says, is a misappropriation of funds and a breach of fiduciary responsibility.

Makes no sense, indeed.

I give Nodler points for creativity, however. I have never heard a “breach of fiduciary responsibility” allegation used to cover up a breach of contract and a breach of good faith. You have to have a highly cultivated sense of mendacity to make this stuff up while summoning outrage for the cameras.

If the politicians had a shred of integrity, they would have told their pension fund managers five years ago that they would under no circumstances get any bonuses when absolute returns were negative. That way, the managers could have evaluated their compensation fairly versus their other opportunities, and decided whether they wished to stay or take their talents elsewhere. Given that the pols agreed to a bonus plan, their ignorance of its terms, or difficulty in explaining to the public why they are making payouts, is not a reason to stiff their employees. At best, if they decided after the fact that they wanted to pay for absolute performance rather than relative performance, then they should recalculate the bonuses earned in past years under this plan on an absolute basis, and pay them consistently. As it stands, the Missouri politicians were content to pay bonuses based on relative performance when peer fund returns were positive, but for absolute returns when the funds are negative.

And that is why politically run systems can’t outperform private sector ones.

Posted by Marc Hodak on under Invisible trade-offs, Politics |

Liberal blogger Ezra Klein is dubious about Obama’s pleas to progressives: that whatever happens in each house of Congress, he will fight in conference to uphold his “bottom lines,” which consist of affirmative answers to these questions:

Does this bill cover all Americans? Does it drive down costs both in the public sector and the private sector over the long-term. Does it improve quality? Does it emphasize prevention and wellness? Does it have a serious package of insurance reforms so people aren’t losing health care over a preexisting condition? Does it have a serious public option in place?

Never mind that he’s claiming with a straight face that a central planning system, which is what a “serious public option” will inevitably devolve into, is likely to produce a combination of widespread availability, decreasing costs, and improving quality–something that no government-run system has ever produced whether it be shoes or schools. And after all this, Professor Bainbridge feels Obama has left some things out:

- Nothing about Americans being able to keep the doctor they have now

- Nothing about Americans who are satisfied with their health care insurance being able to keep their existing policy

- Nothing in it about preserving opt-outs so that those who don’t want socialized medicine can keep private plans that fund procedures and drugs the government is unwilling to cover

- Nothing about how to pay for it without raising taxes to global highs

And then there is that thing that Obama, the progressives, and nearly every one else has left out in their “bottom line,” i.e., the prospect of finding cures for nasty things that don’t happen to have yet been cured. Innovation continues to be the ignored trade-off.

Posted by Marc Hodak on under Executive compensation, Invisible trade-offs |

The Sucker Proxy

While Congress presses ahead on “Say on Pay,” some institutional investors are beginning to rethink their position. The Say on Pay bill would require an up or down vote by investors each year for every public company. Even a small pension fund has investments in thousands of companies. How are they supposed to wade through the SEC-mandated morass that is executive compensation disclosure for every one of those companies sufficient to form an opinion on its adequacy and render a vote?

My firm plows through hundreds of proxies each year in order to determine the relative quality of compensation plans for our research purposes. We employ a team in India to get the data, and a couple of analysts in New York to plow through the data for a couple of months in order to reach opinions about specific firms. We’re down to doing this every other year because the effort is so costly, and the quality of plans don’t really change that much from year to year for any given firm.

Activist investors have sipped this tonic, and have come to a conclusion of their own:

Some shareholders say they have already gotten a taste of say on pay voting and find it unwieldy and time-consuming. The United Brotherhood of Carpenters, whose pension funds have about $40 billion in assets, says it cast more than 200 say-on-pay votes this year at companies participating in the government’s Troubled Asset Relief Program. These companies needed to get their pay plans ratified by shareholders…

“We think less is more,” said Edward Durkin, the union’s corporate affairs director. “Fewer votes and less often would allow us to put more resources toward intelligent analysis.”

Unfortunately, they’re making this case to congressmen who don’t even read the laws that they pass.

Posted by Marc Hodak on July 21, 2009 under Collectivist instinct, Reporting on pay |

This was an amazing transition. Here is the headline, sub, and lead:

Pay of Top Earners Erodes Social Security

Fund Expected to Be Exhausted in 2037

The nation’s wealth gap is widening amid an uproar about lofty pay packages in the financial world.

So, is this an article about Social Security? Wealth distribution? Or pay in the financial sector?

None of the above. It appears to be a critique of tax policy. I say “appears” because this article looks like a poorly edited complaint about how the affluent are not taxed enough in the opinion of the writer. Here is the paragraph among this swampy muddle that comes closest to saying what she is really trying to say.

Social Security Administration actuaries estimate removing the earnings ceiling could eliminate the trust fund’s deficit altogether for the next 75 years, or nearly eliminate it if credit toward benefits was provided for the additional taxable earnings.

Translation: If we take more money from the affluent, or reduce their benefits, we could eliminate the deficit in the social security trust fund.

No plausible actuarial basis is offered for these prescriptions, and no moral basis for why the government’s problem in managing SS becomes a justification for looting the income or wealth of the affluent. Just a gentle suggestion that breaking a deal can help the side that wasn’t screwed.

Of course, the ultimate sleight of hand, here, is that the extra dollars brought in by raising or eliminating the earnings cap on taxes will actually help SS solvency. Every dollar of those taxes will simply be spent on current projects, and future taxpayers will simply have a higher obligation to repay to the “Trust fund.” Bernie Madoff must shake his head in amazement thinking, “What a piker I was.”

Read more of this article »