Posted by Marc Hodak on August 7, 2007 under Collectivist instinct |

A former KGB officer suggests that international lack of regard for our president is merely a reflection of our own disrespect for him. He recollects for us a youthful impression:

My father spent most of his life working for General Motors in Romania and had a picture of President Truman in our house in Bucharest. While “America” was a vague place somewhere thousands of miles away, he was her tangible symbol. For us, it was he who had helped save civilization from the Nazi barbarians, and it was he who helped restore our freedom after the war — if only for a brief while. We learned that America loved Truman, and we loved America. It was as simple as that.

So, his remedy is to stop bashing our own presidents. We should summon just enough propaganda to squelch public disdain about our leader in order to strengthen other’s perceptions about him.

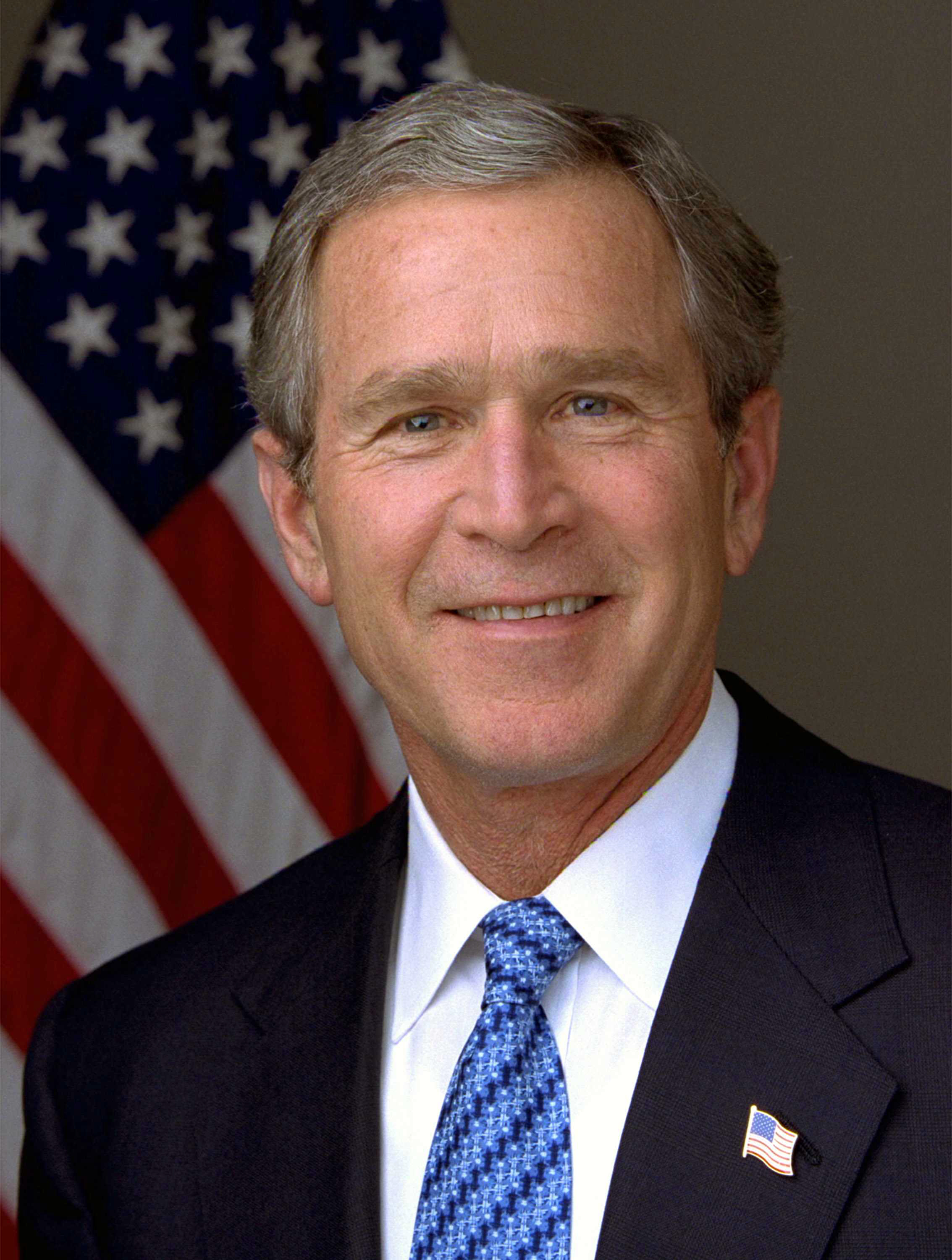

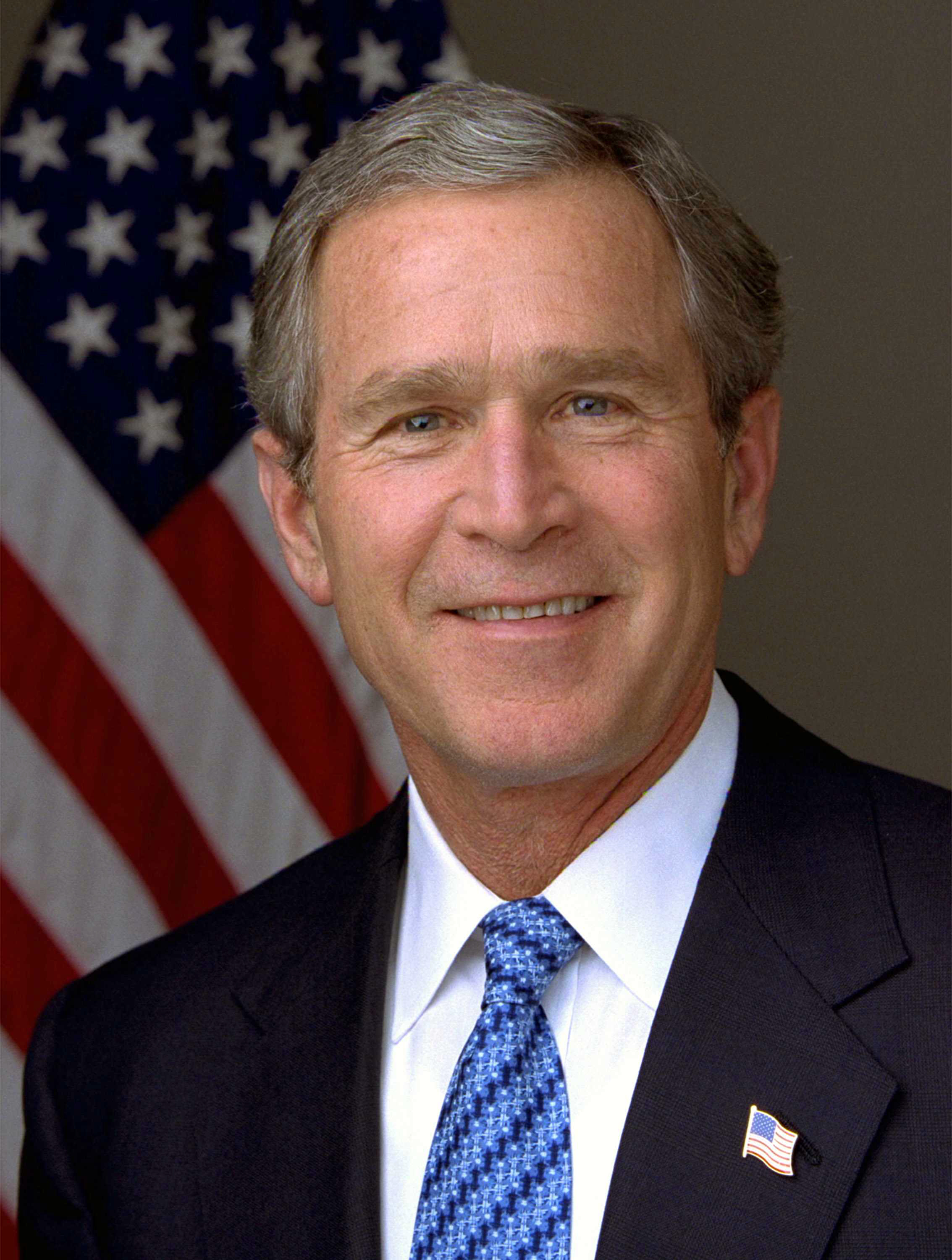

Aside from the principled and consequentialist qualms I’d have about the level of propaganda that would be needed to make Americans feel good about someone like Bush (or any recent president, not to pick on W), I wonder about the value of doing so. Clearly, it helps to achieve “national” objectives for everyone to be behind a leader proposing them. But are national objectives all they’re cracked up to be?

I’m also skeptical about the psychology of former-Soviets, even those of good will towards America. I have had many friends from the former Soviet Union. They have been uniformly smart people, some of them quite brilliant, but nearly all of them possessing a peculiar blind spot with regards to propaganda and the associated freedom of the press. I know that to them, my “knee-jerk” defense of an unfettered press, even one prone to printing lies, seemed equally peculiar. So, when I expressed my doubt about the long-run efficacy of propaganda, I would use my Russian friends themselves as Exhibit A: you won’t find a more cynical people on earth than Russians, and I don’t think it’s genetic. Furthermore, no amount of propaganda got the Russians to forget about the Beatles or blue jeans. Decades of hero worship nurtured by propaganda did not prevent Lenin’s statue from toppling all over the communist world, including in cities named after him. In the long run, I don’t think W’s image can be resurrected with fawning press coverage. If anything, presidents like Lincoln, FDR, Kennedy, and Reagan get far better press treatment today than they got in their own day.

The most disturbing thing about this Russian’s nostalgic recollection, however, is his grown-up expression of a child’s most collectivist impulse–hero worship. Our press already possesses the most annoying tendency to credit collective effort to a single individual, even as it subtly undermines the value of the individual in nearly every other way. They aggrandize individuals because their readers relate to individuals, not ephemeral forces. We buy celebrities, not concepts. The press certainly has an interest in selling us the notion that W’s daily schedule is newsworthy, or that it matters why Brad broke up with Angelina. Even if idolatry is good business in catering to human nature, though, I really don’t see the virtue of supporting it as a matter of public policy.

Posted by Marc Hodak on August 3, 2007 under Patterns without intention |

Every accident, such as the horrific collapse of the highway bridge in Minneapolis, brings on six, predictable steps:

1) Shock – People react to devastation in a visceral way. For a fair percentage of people, the instant response is “OMG,” “Wow,” or even “Cool.” It may take several beats, minutes, or hours before even those of us who exhibit a great deal of empathy in our personal and professional lives finally arrive at a genuine sense of dread about the matter. Just before that moment sets in is where local news is at its best, satisfying what is at this point an insatiable curiosity.

2) Grief – First from those directly affected, then from the rest of us witnessing them, in widening circles. Here, the news process rapidly goes downhill, chasing the “human story” in the form of cameras and mikes in the faces of the distraught, preferably as they are dragged from the river. It’s not the media display of individual grief that is so unwholesome as much as the competition to display it sooner, oftener, and more graphically as the media swarm descends on the situation.

3) Political outrage – They can’t help it. Politicians trade on outrage. Unlike the media coverage of grief, which only gets unseemly when it balloons into a competition of pain, political outrage is unseemly at the outset. Then, the competition begins. That escalating outrage is conveniently directed at the most politically vulnerable link in the chain of causation (or foreigners). Not to underestimate the depth of outrage a politician is capable of mustering, politicians can express it toward several politically vulnerable groups, opponents, and each other all at once. They’re that good.

4) Blame – Any situation where people get hurt on a large scale, no matter how accidental, sooner or later generates a widespread sense that “someone” is at fault. In the case of engineering failure, there is almost never a single reason. Given how few bridges collapse in this country, the most likely cause is a whole chain of improbable decisions and events that, absent any other intervention, would be unlikely to recur in several decades. But the politicians will lead the hunt, with the media close behind, instinctively homing in one of several links in that chain as “the” cause.

5) The Memo – In the witch hunt that follows, eventually proof will show up that someone, somewhere, wrote a memo predicting that this would happen. Sort of. It will rarely be a definitive prediction, such as “Structural defect A will lead this bridge to fail in the next six-to-twelve months if we don’t do anything.” It will be a more general prediction like, “Deficiency A across our system of bridges may, if untreated, eventually lead to severe problems, or even catastrophic results.” This memo will, of course, be indistinguishable from thousands of similar memos that predict disasters of indeterminate timing and consequence all over the nation all the time. But as far as the blame hunters are concerned, here is the smoking gun. Every can see the smoke with the perfect clarity of hindsight bias.

6) Prosecution – The person who ignored “the memo” becomes a useful scapegoat. And his boss. And their co-conspirators. The eventual trial is, of course, just another part of the show that this whole disaster becomes, the crescendo of blame and outrage, a chance for the people to march from the countryside with their torches through the public square…oh, wait, wrong century.

Not.

You’d like to think that a disaster, unfortunate as it is, can be used as a learning opportunity. If we never have an engineering failure, then things clearly have been over-engineered. After a failure, if the process is done right, everyone has the incentive to contribute information related to the chain of events so that resources can be focused on the weakest link.

Blame and outrage destroys that process. It forces everyone associated with the accident to hide the very information most closely related to the weakest link. At its worst, when bad judgment criminalized, the only people benefiting are those doing the punishing. The rest of society bears the cost of overreaction.

Anyway, that’s the prediction here about how this accident will evolve into tragedy.

Posted by Marc Hodak on August 1, 2007 under Invisible trade-offs |

The U.S. Election Assistance Commission had $3 billion to spend on improved voting processes. They released a report detailing the amount of spending so far by each state. This is a pretty straightforward report dutifully produced by an bureaucracy whose name certainly evokes the “we’re here to help” joke. However, I think it’s very interesting how the news outlets picked it up.

The Wall Street Journal noted that that “just 60% of the $3 billion” had been spent. “Just” sounds like “not enough.” The AP, in a story picked up by the New York times and others, sported the headline, “Some States Slow to Spend Voting Aid.” There is no mistaking the connotation of being “slow.” This article‘s headline said that the states were “behind.” Who wants to be behind on something?

But is it bad that the states have not yet spent 100 percent of these funds allocated to them? The press is clearly implying that these underspending states may not be living up to their responsibility to provide secure voting, possibly forcing us to relive the Florida 2000 debacle. But is that what is really happening? Or might it, perhaps, be a sign that some states are less deliberate or more spendthrift than others? Or that some states are merely more bureaucratic and indecisive?

Or, is it possible that the federal government somehow, perhaps, misallocated $3 billion of funds to the states?

Read more of this article »