Improving Objectivity

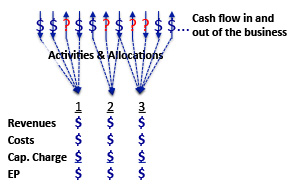

Revenues and costs are sometimes allocated across periods in anticipation of cash coming in or leaving the business. In such instances, estimates must be made about future collections or spending, (e.g., receivables, reserves, allowances, etc.). Such future cash flows can usually be anticipated with reasonable accuracy, but are never certain, and sometimes require considerable judgement. The effects of such judgments can be significant enough to undermine objectivity and confidence in the measure.

Situation 1

We are having a great year. Maybe we should stash away some of our gains in a couple of reserves?

Result with unadjusted EP

- EP gain is moderated

- Management performance (and perhaps reward) gets reduced

- Managers not involved in accounting decisions may resent the shorting of profits

Situation 2

Things are not working out this quarter. Maybe we should draw down some from our reserves?

Result with unadjusted EP

- EP loss is disguised

- Management looks better than they otherwise would

- Reinforces the idea that accounting tricks can make up for poor performance

Why bother manipulating reserves?

Management would rather produce smooth earnings growth than risk an earnings decline in any period. Smooth earnings growth is considered by external investors to reflect lower risk. However, if the smoothed earnings are a function of accounting manipulations, they merely create the illusion of lower risk. While everyone feels better about these earnings in the short run, a number of situations can arise that reveal the deception, shattering confidence in management.

Conclusion

Sometimes, it can be easier to "manage the numbers" than to manage a business. Minimizing the use of discretionary reserves for managerial accounting--especially if variable compensation is tied to the measure--reduces the temptation to "manage the numbers," and preserve confidence in the numbers used track performance.